Whenever I hear about directors preparing to take on so-called unfilmable books, I find myself filled with anxiety. When I heard that Lana and Andy Wachowski, the siblings behind the Matrix movies, were attempting to adapt David Mitchell's labyrinthine novel Cloud Atlas, I wanted to call them up and beg them to put the book down and back away slowly. Don't do it. Why not make Richard Price's Lush Life instead? Great novel, eminently filmable, never been filmed. Nor has Donna Tartt's The Secret History. Or Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash. There's plenty of low-hanging fruit out there.

Also, while I've got you: How the hell did you persuade somebody to give you $100 million to try? Whether or not Cloud Atlas the movie is any good, the pitch must have been a damn masterpiece.

A lot of the buzz around Cloud Atlas, which comes out on Oct. 26, is about how hard it is to turn this book into a movie--which it is. It's hard enough to read in the first place. Mitchell's novel consists of six separate stories, each set in a different historical period, each nestled inside the next, Russian doll--style. There's a corporate thriller, a caper in a nursing home, a future dystopia; the stories are interrelated thematically, but on a literal level they're connected only by leitmotifs and slender filaments of coincidence. The Wachowskis and their collaborator, Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run), approached the challenge by dicing each story into individual scenes and then interleaving them with one another, effectively telling all six simultaneously.

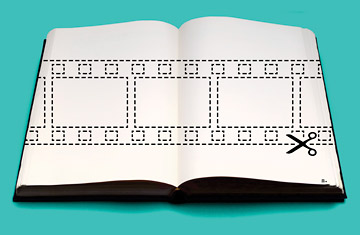

You can see why they did it, and the reason says a lot about the differences between books and movies. Reading a book is a much less linear experience than watching a film. In a book you can flip back and forth, skim and reread, stop and start. You can pause the action and go back 100 pages to remind yourself who all the characters are and how they know one another, then forge ahead again. Movies, by contrast, are a forced march. They never stop or slow down. In a movie you can't pause the story of a young clerk shipwrecked in the South Pacific, tell five other stories and then go back to the first one two hours later and expect the audience to remember what was going on. Which is why in order to become a movie, Cloud Atlas had to turn from a Russian doll into something more like a braided ribbon. In the process, it loses the elegance of Mitchell's structural conceit, in which the stories get set and baited like steel traps, one by one, and then spring shut in an elegant cascade. But adaptation is never a lossless process.

For some reason, the basic incompatibility between books and movies is something that we--writers, filmmakers, audiences--have to discover and rediscover over and over again. It's as if we can't stop trying to jam an Ethernet cable into a USB port, even though, yeah, it really probably isn't ever going to fit. Having only just recovered from Cosmopolis and John Carter, we're bracing for Cloud Atlas, Wuthering Heights, Life of Pi, Midnight's Children, On the Road, Anna Karenina, The Hobbit (times three) and Ben Stiller's take on Walter Mitty, not to mention a new Great Gatsby (its fifth adaptation) and Great Expectations (there are about a dozen).