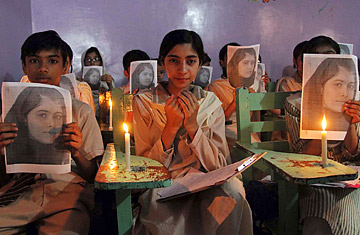

Children in Karachi hold a vigil for Malala's recovery.

Before the truck can roll to a halt, a throng of little boys hops out of the back. They run to join the men chanting on a grassy street corner in a posh neighborhood of Pakistan's capital, Islamabad. A man gives one of the young protesters a handwritten sign that says WE CONDEMN TERRORISM. He holds it up in front of his tiny chest. "Terrorism!" one of the men shouts, pumping his fist. "We condemn it!" the crowd responds. A city policeman watches from the periphery, a Kalashnikov leaning against his leg. "Malala!" another protester shouts. "Zindabad!" the crowd shouts back. "Long live Malala!"

It has been more than a week since Malala Yousafzai, a 14-year-old blogger and activist, was shot in the head while riding in a van on her way home from school, and people across Pakistan are not done being angry. From Islamabad in the north to Karachi in the south, demonstrators in all Pakistan's big cities have denounced the Taliban's brazen attack on the girl and two of her classmates in northwestern Pakistan's Swat Valley.

Malala, who is in stable condition after surgery, was flown to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England, on Oct. 15, and her British doctors say she could make a good recovery but she has several weeks of treatment ahead of her. She leaves behind a nation trying to understand why, despite years of fighting the Taliban, extremists can still attack children with impunity. Bound by outrage, Pakistan seems united — a rare occurrence. "The mood of the people is unforgiving," says Shaukat Qadir, a retired brigadier in the Pakistani army. "We have to do something."

But what? Alas, there is little agreement about that. Within hours of the Oct. 9 attack, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan had claimed responsibility, calling Malala's advocacy for children's rights and education "pro-West" and "against Taliban." Since then, "nobody has condoned or endorsed the attack," says Mubashir Akram, a former political analyst for the U.S. embassy in Islamabad. "But when it comes to condemning the attacker, there is a division." As the anti-Taliban protests continue, another wave of outrage is gathering force. Islamist groups like Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl say the international publicity lavished on Malala's case is diverting attention from Pakistan's other problems, especially the widely criticized campaign of U.S. drone strikes against militants on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Hundreds of civilians have been killed by the drones since 2004, including 176 children, according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. "[The Islamists] say, O.K., this is bad, but what about the drones?" says Akram.

It isn't just Islamists raising that question. Mainstream political leaders in the border areas — which have long been affected by extremist violence, military offensives and drone strikes — also wonder at the sudden attention. "There are so many young girls who have been killed in the last few years by drones and suicide attacks," says Ajmal Khan Wazir, a central senior vice president of the Pakistan Muslim League (Quaid-e-Azam) and a resident of South Waziristan. "Everybody is crying for Malala, but nobody is crying for the other Malalas." This cycle of violence and recrimination makes decisive action against her attackers unlikely.