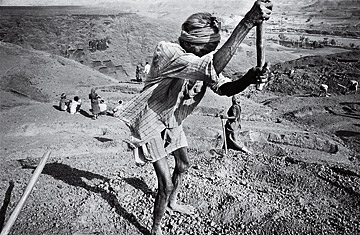

Villagers work at a site set up under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

(2 of 2)

STUCK IN THE MIDDLE

If you drive a few hours into Uttar Pradesh's green fields, you begin to grasp just how ambitious this law really is. Nearly 200 million people (by population, this single Indian state would be the fifth largest country in the world) inhabit an area roughly the size of the U.K. Some 40% of them live below the poverty line. U.P., to use its common abbreviation, is one of the places that stand to benefit most from MGNREGA, but it is also one of the places where the law has had the hardest time getting off the ground, because of a combination of conservative attitudes toward women, stark caste-and-tribal discrimination and low levels of education. "Uttar Pradesh is one of the most difficult states," says Reetika Khera, an assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi who has studied and written about the law extensively. "Everything is a problem there."

Ramkali appreciates the help she's been getting. She's even being paid to work on her own land. The problem, she says, is that she is not being paid on time. "I'll get 10 days of work and spend eight days trying to get our money," Ramkali says. It's a common complaint in villages all around this part of the state. Payments are made via electronic banking instead of cash. The upside is that there is less opportunity for corrupt bureaucrats to skim off workers' wages. The downside is that the electronic system is slow.

Kaimaha isn't the only village where the program gets mixed reviews. In nearby Basila, a group of women sit inside a home, talking about the pond they are being paid to dredge out and revive. "Before, officials would say, You're women, what can you do?" says Kalavati, one of the workers. MGNREGA mandates that a third of its beneficiaries be women, but they are still passed over for many jobs because local leaders don't think they're as strong as men, or because they can't leave their children at home. (The act also mandates that child care be available at each work site, but many places aren't compliant.) Last year, women in U.P. only had a 17% rate of participation in MGNREGA projects, compared with the national average of 47%.

With help from a local NGO, Kalavati and her neighbors got organized and called a meeting to demand work from their village leader, or pradhan. Now more than 150 women from four different villages are earning wages at the pond. Kalavati says she makes more than her husband these days. "The sense of entitlement has grown," says Raghav Gaiha, a professor at the University of Delhi. "People are demanding work." The problem is that it's less likely to happen without the intervention of a civil-society group. A worker, for instance, needs to keep written proof that she or he has asked for a job, both to follow up on the request and, if work is not given to them, to collect unemployment wages that the law guarantees. But in most places, people don't know to ask for a confirmation of their registration for work. Nor do they know that they're entitled to unemployment benefit. In recent years, only a handful of workers across India have been awarded such benefit, and then only after months of campaigning on the part of NGOs or activist groups. "It only works when people are telling them [what they're entitled to]," says Arundhati Dhuru, an adviser to U.P.'s supreme court. "Why should you have to fight a battle for it?"

Many say the program's infrastructure is simply too weak to tackle all that it promises. Initially, it was introduced in 200 of India's poorest rural districts. But by 2009, it was rolled out to every rural district in the country, a move that some say has directed precious funds to wealthier states like Gujarat and Kerala while overstretching administrative resources in places like U.P., where they're needed most. MGNREGA's annual budget, which because of the program's demand-driven nature is not fixed but estimated, more than tripled from roughly $2.5 billion in 2006—07 to about $8 billion in 2011—12. Manoj Singh, U.P.'s former state commissioner of rural development, recalls that his office struggled to deal with the influx of funds. "You are pouring in money without creating a delivery mechanism," Singh says. "It was like water was falling, and we were rushing to catch it."

In places where local leaders are active, the program tends to work better. Raj Kumar Yadav, the 32-year-old pradhan who governs Kaimaha and 22 other hamlets, immediately saw the potential of MGNREGA to improve his constituencies' roads and conditions for farmers when he was elected two years ago. He makes sure meetings to discuss potential projects are publicized, and he says he personally takes residents to the higher-level government offices if they aren't being paid on time. "This is a really backward area. I wanted to do something for it," Yadav says. "There's still a lot of work to do."

Not all villages are in such good hands. Many hamlets are deeply divided by caste or faction. In the nearby village of Byur, a group of residents crowd around to complain that they are not getting any work under MGNREGA. They say people living in the other half of the village, who are of a different caste, are getting jobs. One young man listens to the crowd for a few minutes and sums up why laws like MGNREGA, or any other laws, aren't working: "Whatever the [local council] wants to do, somebody has a problem with it, so nothing gets done." Shah, the Planning Commission member, says one of the schemes' loftier goals is to spur residents in places like Byur to respond to these kinds of problems by becoming more engaged in local politics. "The hope is that people don't remain at the mercy of an ineffective pradhan, but will vote him out," says Shah. "We are potentially changing the face of democracy at the grassroots."

THE GOOD FIGHT

If Mgnrega is the world's largest employment-guarantee law, it must also be one of the most scrutinized. There has been no shortage of studies on MGNREGA's impact in the past six years, yielding both encouraging and discouraging findings. The Ministry of Rural Development, which is responsible for the law's implementation, launched earlier this year a series of reforms designed to address some of the more endemic problems. Widely known as MGNREGA 2.0, the revisions include, among other things, provisions that beef up the program's administrative resources and create more ways for workers to record their registration for work, including by mobile phone. They also augment the scheme's computerization system so that workers are registered automatically for unemployment benefits and get paid when they should. Given time, these reforms should help free up some of the logjams that have developed in the past six years. Whether they can help realize the act's full potential — to put a stop to India's grinding cycle of rural poverty and to neutralize some of the inequities of village life — is unclear.

On a warm afternoon in September, hundreds of men and women sit under a sweeping neem tree in Sitapur, another district in Uttar Pradesh. A few women watch from the side with babies on their hips, while men shoo monkeys away from the meeting's periphery. The participants, organized by a local civil rights group called Sangtin, have come from 20 different villages to talk about different problems, including the obstacles they've encountered trying to get work under MGNREGA. A woman in a green sari stands up and describes her village's struggle to get paid its full wages for a project it completed. When she finishes and sits down, another woman stands up after her. "This is an old problem," she observes. "At every stage, you have to fight it out." As long as there are women and men like these who are willing to join the fray, there is hope that it might be a fair fight someday.

— with reporting by Alka Pande / Lucknow