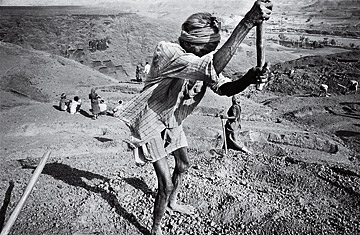

Villagers work at a site set up under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

Ramkali ducks inside her front door, whisking past the ashes of breakfast's kitchen fire and a young cow nosing a basket of fodder. The morning rain has let up, and Ramkali (who, like many Indian villagers, goes by one name) points to some lemon and guava saplings in her backyard. Other residents of Kaimaha, her village in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, helped plant them. "When I can't get other work, maybe I'll be able to use some of the fruit and sell it," she says, looking at a scrawny tree.

Ramkali's neighbors, nice as they may be, are not helping out of the goodness of their hearts. The government of India is paying them to do it. In 2005, India embarked on what may be the most ambitious social-welfare program ever conceived, now called the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, or MGNREGA. Channeling the Depression-era New Deal in the U.S., the law guarantees 100 days of paid work each year to any household that wants it. Every day across the country, millions of workers from Kerala to Kashmir build roads, dig wells and plant crops and trees, among many other things, in return for a daily minimum wage. Last fiscal year, some 50 million households, or about a quarter of India's rural homes, were working under the law on nearly 740,000 new projects around the country.

That makes the government of India the largest employer in the world, if not in history. Whether that's a good thing is a matter of debate. The law, which went into effect not long after the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) came to power, has been one of the signature projects of Congress Party leader Sonia Gandhi. It has evolved and struggled alongside its political champions, and become a kind of talisman for the performance of the UPA itself. Supporters laud the vast commitment of rupees to the improvement of the lives of millions of rural poor; critics say UPA's enthusiasm for welfare programs has helped put India's economy in the precarious spot it is today. How the scheme plays out in hundreds of thousands of villages, worlds away from New Delhi's ministerial meeting rooms, also offers a priceless — and sometimes painful — glimpse into the health of the nation's greatest asset, its democracy. "When local [elected bodies] are functioning more democratically, the employment generation is better," says M.V. Rao, director general of the National Institute of Rural Development. But, he says, "in some parts of the county, there are still feudal forces at large that act to the detriment of the program's progress."

The transformational potential of a guaranteed wage in an underemployed nation like India cannot be denied. Unlike previous labor schemes, MGNREGA enshrines the right to work in India's constitution. People tell local officials that they want to work, and the parties come up with community projects that will benefit everyone. Since it was first rolled out in 2006, MGNREGA wages have increased an average of 81%. In many places, pay in the private sector has risen in tandem. The law has helped stem forced migration and reduced child labor. It has given millions of women a reliable income for the first time and allowed members of low-caste and tribal communities a foothold in an economy that has pushed them aside. "It was a paradigm shift," says Mihir Shah, a member of the nation's Planning Commission, who works on MGNREGA. "We were saying, 'Business as usual won't do.'"

Changing that business has not come easily. The rowdy brand of democracy on display in India's cities is absent in most villages, where people's awareness of their rights tends to be weak. That means the law often doesn't work: many people who are desperate for employment don't know that the government promises it to them. Even when people know about their new right, ushering millions of demands through the tiers of India's meandering bureaucracy is easily derailed by chronic understaffing and corruption. A lament has sprung up among the bureaucrats who have been tasked with administering the law: Jo NREGA karega wo marega. Roughly: Take on NREGA, and you are doomed.