(10 of 11)

Bain quivered with emotion, Tierney says, and "his reaction was, 'This is my company. I am not negotiating.'" Still, Romney gave him a day to consider the deal. Bain and his co-founders accepted. Mentor and protg had reversed roles.

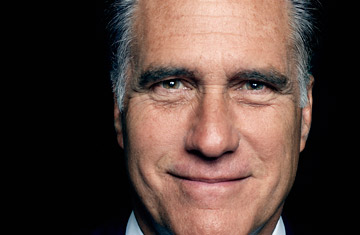

THE MAKINGS OF A PRESIDENT

High-performing people in their prime tend to hang on to the habits that brought them success. Romney has promised he will do just that if he carries his business expertise to the Oval Office.

No career can fully prepare you for the incomparable responsibilities of the presidency, but Romney's business record displays qualities that nearly anyone would want to see in the White House. He has been a sharp judge of managerial and analytic talent, recruiting and holding the loyalties of able people in his investment firm and in the companies he bought. He could not have succeeded in management consulting or private equity without considerable skills as a strategist, salesman and negotiator. Romney's accomplishments demonstrate "a very high level of intelligence, an ability to size up the situation and put the pieces together, to see the big picture, where they're trying to go and what they're trying to accomplish," says Margaret Blair, a Vanderbilt Law School economist who teaches management law. "Those are good things that would serve a person well who is trying to be the President."

Yet there are habits of Romney's business career "that I think don't translate at all," she says. "If you walk in the door and you're from the private-equity firm that has just bought the controlling interest in some company, you literally own the place. You can tell people what to do, and they'll do it. That's not the way politics works."

Romney guided Bain Capital through its stratospheric rise with an extraordinarily selective approach to problem solving. He and his partners did not have to concern themselves with the whole wide world of corporate transactions. Even as a multibillion-dollar company in its later years, Bain Capital needed only a few big wins to earn its high returns. Romney learned to filter out most of the files that reached his desk, directing his attention to the fraction that showed the most promise and lowest risk.

To do all that well is very far from easy, but that is not the province of a Commander in Chief. Only the hardest problems head to the Oval Office, many of them with high stakes, high risks, ambiguous evidence and only imperfect outcomes. The problems come in twos and threes and tens, allowing little uninterrupted time for deep reflection. And a President can sidestep very few of them, however unattractive the odds of success.

Bob White, a longtime partner who now serves as one of Romney's closest campaign advisers, believes otherwise. "In business you can walk away from some things, but you can't when you're governor, and you can't when the Olympics needed to be put on," White says. "He did work in private equity and was involved in lots of companies, but then he's taken all that he has learned and applied it elsewhere and succeeded under enormous pressure in turnaround situations again and again."

The question facing voters is whether they believe Romney's skills as a businessman can transfer and help him succeed in the less empirical realm of politics.