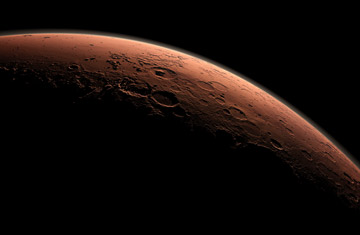

This computer generated view depicts part of Mars at the boundary between darkness and daylight, with an area including Gail Crater beginning to catch morning light.

(3 of 5)

Curiosity's landing site is a formation known as Gale Crater, 96 miles (155 km) wide. Located in the southern Martian hemisphere, it is thought to be up to 3.8 billion years old--well within Mars' likely wet period and thus once a large lake. A 3-mile-high (4.8 km) peak known as Mount Sharp rises in its center, with exposed strata layer-caked down its sides. Channels that appear to have been carved by water run down both the crater walls and the mountain base, and an alluvial fan--the radiating channels that define earthly deltas--is stamped into the soil near the prime landing site. All this is irresistible to geologists searching for the basic conditions for life. "We're hoping to find materials that interacted with water," says Grotzinger. Previous landers, he says, did some soil analysis, "but this time we'll find the actual chemicals."

Curiosity will conduct that search in a lot of ways. The rover's arm will scoop up samples of soil and deliver them to an onboard analysis chamber, where they will be studied by a gas chromatograph, a mass spectrometer and a laser spectrometer, looking for telltale isotopes, gases and elements. Chemical sniffers will sample the Martian air for carbon compounds--especially methane--which are the building blocks and by-products of life. Martian geology will be studied with a long-distance laser that can blast a million-watt beam at rocks up to 23 ft. (7 m) away, vaporizing them and allowing a spectrometer to analyze the chemistry of the residue. An onboard X-ray spectrometer will do similar work on rocks near the rover. "With X-ray diffraction, we can really nail down what kind of mineral is there and how those rocks have formed," says deputy project scientist Joy Crisp.

Most appealing for the folks back home will be the 17 cameras arrayed around Curiosity. They will have the visual acuity to resolve an object the size of a golf ball 27 yd. (24.7 m) away and the resolution to capture one-megapixel color images from multiple perspectives. The sharpest of these imagers is mounted atop the rover's vertical mast, which, now extended, rises 7 ft. (2.1 m) above ground. "You could not look this thing in the eye unless you were an NBA player," says mission systems manager Mike Watkins.

Though Curiosity will soon become a rolling, multiarmed, 17-eyed science lab, for now--after only a handful of days on the surface--it's still just opening its eyes and powering up. "We first have to make up a plan for where we are and how we're going to operate," says Watkins. "Then we'll start handing over the keys to the science team."

The Space Card

The impulse to sentimentalize Curiosity--to treat it almost like a human astronaut--is hard to resist. "The rover is getting ready to wake up for its first day in a new place," said mission manager Jennifer Trosper at an early postlanding news conference. Describing what the science team's work schedule will be like, Watkins says, "The rover's day ends on Mars around 3 or 4 p.m. The rover tells us what she did today, and that ... lets us plan her day tomorrow."