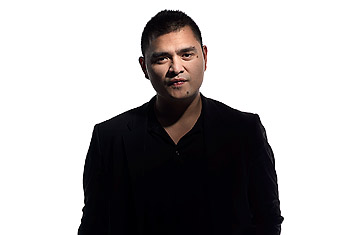

Jose Antonio Vargas

UPDATE: Shortly after Jose Antonio Vargas' story on the issue of the undocumented was published in TIME, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security announced that it would no longer deport young undocumented residents who qualify for the DREAM act. Those eligible will receive work permits.

'Why haven't you gotten deported?'

That's usually the first thing people ask me when they learn I'm an undocumented immigrant or, put more rudely, an "illegal." Some ask it with anger or frustration, others with genuine bafflement. At a restaurant in Birmingham, not far from the University of Alabama, an inebriated young white man challenged me: "You got your papers?" I told him I didn't. "Well, you should get your ass home, then." In California, a middle-aged white woman threw up her arms and wanted to know: "Why hasn't Obama dealt with you?" At least once a day, I get that question, or a variation of it, via e-mail, tweet or Facebook message. Why, indeed, am I still here?

It's a fair question, and it's been hanging over me every day for the past year, ever since I publicly revealed my undocumented status. There are an estimated 11.5 million people like me in this country, human beings with stories as varied as America itself yet lacking a legal claim to exist here. Like many others, I kept my status a secret, passing myself off as a U.S. citizen — right down to cultivating a homegrown accent. I went to college and became a journalist, earning a staff job at the Washington Post. But the deception weighed on me. When I eventually decided to admit the truth, I chose to come out publicly — very publicly — in the form of an essay for the New York Times last June. Several immigration lawyers counseled against doing this. ("It's legal suicide," warned one.) Broadcasting my status to millions seemed tantamount to an invitation to the immigration cops: Here I am. Come pick me up.

So I waited. And waited some more. As the months passed, there were no knocks on my door, no papers served, no calls or letters from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which deported a record 396,906 people in fiscal 2011. Before I came out, the question always at the top of my mind was, What will happen if people find out? Afterward, the question changed to What happens now? It seemed I had traded a largely hidden undocumented life in limbo for an openly undocumented life that's still in limbo.

But as I've crisscrossed the U.S. — participating in more than 60 events in nearly 20 states and learning all I can about this debate that divides our country (yes, it's my country too) — I've realized that the most important questions are the ones other people ask me. I am now a walking conversation that most people are uncomfortable having. And once that conversation starts, it's clear why a consensus on solving our immigration dilemma is so elusive. The questions I hear indicate the things people don't know, the things they think they know but have been misinformed about and the views they hold but do not ordinarily voice.