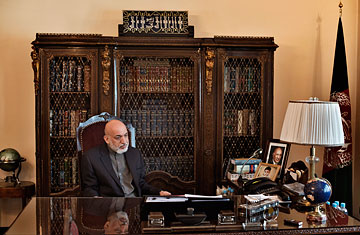

The isolated leader Karzai has become a virtual prisoner of the presidential palace, cut off from his country

(3 of 3)

That cable, along with public accusations of fraud during the 2009 presidential election, marked the nadir of U.S.-Afghan relations. They have never really recovered; as a former U.S. government official tells Time: "Karzai has pushed the U.S. from crisis to crisis." An enraged Karzai responded by turning away from Washington, replacing advisers he suspected of being pro-Western with a cadre of anti-American ideologues. "The West has been against me, clearly," says Karzai.

The irony is that with no party and no natural constituency in his native country, Karzai's power has largely stemmed from his ability to command international forces and funds. With both vanishing by the day, Karzai is finding that his needs may be diverging from those of his nation. In order to keep Afghanistan on a stable path, he will have to sublimate self-interest to the greater good.

The early indications are not promising. Andrew Wilder, director of the Afghanistan and Pakistan programs at the U.S. Institute of Peace, cites the U.S.-Afghan Strategic Partnership Agreement, which was signed in early May after a contentious process. Karzai's insistence that certain elements of the compact — which lays out security and economic relations between the two countries for another decade — be put aside for later consultation appeared to be a stalling tactic designed to preserve his own power for at least another year, at the expense of Afghanistan's security. "It is in Afghanistan's interest to have a strong relationship with the U.S., both as a deterrent to the Taliban and to guard against interference by neighboring countries," says Wilder. "The longer that process takes to finalize, the greater the chance that interest in the U.S. will dry out." And with it, Karzai's last remaining bargaining chips.

After Karzai

Karzai says he is troubled by Afghan fears that the NATO withdrawal will bring a Taliban conquest in its wake. He chalks it up to media propaganda seeking to justify a continued international military presence in his country. Karzai believes the departure of NATO will mean that the bulk of the Taliban will no longer have a reason to fight. "When [NATO leaves], the Afghan people will be more effective in their fight against terrorists," he says emphatically. "So I have no worry about that."

But Karzai may be out of touch with what's actually happening in his country. Security restrictions keep him bottled up inside the presidential palace. It's been seven years since Karzai last walked around his capital, seven years of assassination attempts, bombings, attacks and riots. Still, he says he longs for nothing more than a stroll down the newly paved streets, a moment to consider the crystalline growth of blue-glass office blocks and half-finished shopping malls that are the hallmarks of Afghanistan's faltering wartime economy.

In two years, Karzai will get his wish. By law he will have to step down at the end of his second term, clearing the way for Afghanistan's first-ever democratic transition of presidential power. Even though speculation is rife that Karzai will attempt to prolong his presidency, he says he has no intention of staying a day longer than his allotted term. "Beyond that I will be illegitimate," he tells Time. But while Karzai may be willing to leave the palace, he's not entirely willing to relinquish power — at least not yet. Finding a successor, he says, is "one of my perhaps most important responsibilities" — but does Karzai want a strong successor, or just a weak proxy?

Afghanistan will be vulnerable enough once foreign troops depart, but if Karzai continues to manipulate the levers of power, the outcome may be even worse. "If there isn't a credible election, this could be another fault line for greater instability," says Zalmay Khalilzad, a former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan. Whether Karzai can stand back and let the Afghan people decide where they want to take their country, or whether he might swing the election illegally, will determine the future of Afghanistan as much as the contentious debate over how many foreign troops should stay on past 2014.

"The best thing Karzai can do to be a historic figure is to allow a peaceful transfer of power and not go the Putin route," says U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham, a Republican highly involved in Afghan policy. "[Karzai] does have the right to help pick the next President, but if they try to do it in a way that's outside good business practices, it will ruin his legacy." Karzai himself knows the next two years will be decisive for his career — and his country. "Eventually it's the Afghan people and what they do that will determine the future of Afghanistan," he says. "If we as a nation do the right thing and establish a government that is in the service of the Afghan people, we would not at all be damageable." The question, after all this time, is whether Karzai is the person to do it.

—with reporting by Jay Newton-Small / Washington and Walid Fazly / Kabul