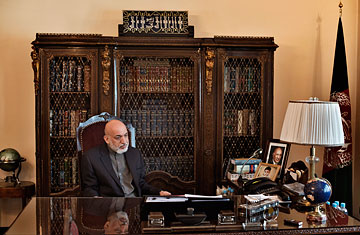

The isolated leader Karzai has become a virtual prisoner of the presidential palace, cut off from his country

(2 of 3)

Yet the Afghan army meant to give force to Karzai's words is still embryonic. The goal is to reach 195,000 trained troops by October, along with an additional 157,000 police. As NATO forces hand districts over to the Afghan National Security Forces, some international troops will stay behind in an advisory capacity. Others will be redeployed to fill security gaps elsewhere in the country. The rest will go home. According to General John Allen, the top U.S. commander in Afghanistan, 23,000 U.S. troops will be on their way out before September, leaving some 68,000 American military personnel in Afghanistan — the number of troops present before Obama's 2009 surge. As NATO stands down, Afghan forces will need to stand up.

For now, though, there's a vacuum — one with consequences for the Afghan economy as well as security. When foreign forces depart, so too will the wartime funding and development aid that have inflated the Afghan economy. Uncertainty about the future has stifled the Afghan private sector and paralyzed foreign direct investment. Even comfortable Afghans are mired in malaise, afraid that the good times — such as they are — won't last. "When the Americans leave, the Taliban will come the next day," says Mohammad Jabar, a 25-year-old university student who likes to spend his Saturday afternoons bowling in Afghanistan's only alley, which opened in Kabul last fall. "We are praying to God not to let them come back."

That pervasive fear has spread to affluent Kabul neighborhoods like Sherpur, where wedding-cake narcovillas, once impossible to rent for under $10,000 a month, now stand unwanted. Some people are voting with their feet — last year 30,000 Afghans legally sought asylum abroad. Corruption is mounting, as everyone from high-level ministers to traffic cops stuff their pockets before funds dry up. The Afghan central bank reports that $4.6 billion in cash was taken out of the country last year, a flight of capital nearly equivalent to the country's $4.8 billion annual budget.

The insecurity and corruption cannot all be blamed on Karzai, but he's done too little to stem it. "There is corruption in Afghanistan, no doubt," Karzai admits. But he adds that international donors have themselves fueled that corruption with opaque contracts and attempts to curry favor with prominent politicians. Before I could point out that corrupt parliamentarians were the government's responsibility no matter where the money came from, Karzai changed the subject.

His unwillingness to see the bigger picture does not bode well for his ability to take Afghanistan through this difficult transition, says Ahmed Rashid, an expert on the AfPak region. "I don't think he really understands the problem. He is thinking narrowly of his own survival, his family's survival and regime survival, and not what is best for the country."

The Unlikely Leader

But then, Karzai was never really meant for power. The middle son of an influential tribal leader from Kandahar, he was sent to study in India in 1976, where he embraced Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence and, to a certain extent, vegetarianism. (In a country where the powerful eat meat at nearly every meal, Karzai notably limits his consumption — and that of the palace — to three days a week.) When an international conference on Afghanistan appointed Karzai interim President in 2001, it had little to do with his leadership abilities. He was the lowest common denominator, inoffensive in a country plagued by ethnic divisions where few leaders could boast clean hands. "Karzai is a good person, pure and sincere," says former Afghan President Sibghatullah Mojaddedi. "But he is not a person who is really strong, who can be a big man and control everything in the country."

At the same conference, Karzai was presented with a ready-made Cabinet designed to balance ethnic rivalries for power. It would soon become a liability. He had no political power and no ability to direct, or sack, members of his Cabinet. When Karzai was elected in a landslide in 2004, he could have taken a stand, dismissing the power-seeking warlords and political operatives that had corrupted his Cabinet. But by then it was too late. "He can't be blamed for how he got his start," says former spokesman Waheed Omar. "What he can be blamed for is that when he got into a position where he could reverse those early, bad decisions, he did not."

The result has been an inconsistent Afghan government that lacks the enforcement power needed to root out corruption and put an end to opium farming and heroin trafficking. The West, and particularly the Americans, became increasingly frustrated, as former U.S. ambassador Karl Eikenberry put it in a 2009 diplomatic cable that was subsequently leaked: "Karzai is not an adequate strategic partner. [He] continues to shun responsibility for any sovereign burden, whether defense, governance or development."