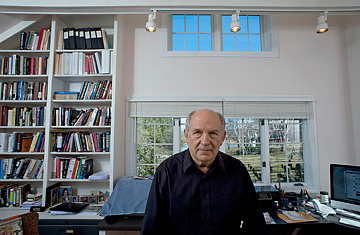

The hermit of Burkittsville. Murray gets perhaps one call a week at his rural Maryland home

The conservative social scientist Charles Murray has spent much of the past two decades occupying a peculiar place in American public life: having suffered a broad shunning, he has been living in the aftermath of disgrace. Ever since the furious reaction to his 1994 book The Bell Curve left him branded, as Murray says ruefully, "a pseudoscientist and a racist," he has been living out a form of partial exile in Burkittsville, Md. That book, which he wrote with Harvard psychologist Richard Herrnstein, surveyed an array of social data and argued that the old, fluid American hierarchies had been replaced by a new structure with a rising cognitive elite at the top. In the single chapter that caused the controversy, Murray and Herrnstein discussed intelligence differences not only between individuals but also between groups, and in particular between racial groups. The specter of a permanent elite and underclass arranged in part along racial lines was both abhorrent and--many academics felt--statistically dubious, and soon Murray's name was mostly a signifier of how vicious and divisive the '90s culture wars had been. He kept his post at the American Enterprise Institute think tank, but he was otherwise forgotten. "I will get, and I'm not exaggerating, maybe one phone call a week, at most, from anybody," Murray says. "I am really a hermit."

But Burkittsville (pop. 176), the scene of his isolation, turned out to hold insights of its own. In the nearby swath of rural Maryland, Murray noticed a once distant form of listlessness creeping in. Local tradesmen could no longer find suitable assistants, workers who would reliably show up on time and stay through the working day. Families that had been stable for decades saw their unmarried daughters having babies, and young men with no obvious means of support fathered children with several different women. Murray believed that the culprit wasn't drugs, exactly, or some local economic collapse but something more subtle and profound. For years, he had argued that the cause of poverty in the black inner city was not simply economic, that the ghetto's culture had helped cleave it off from the American mainstream. Now he saw the same habits taking root in communities that are rural and virtually all white. "All of those things," he says, "have been going on out there." It occurred to him that he might be seeing the creation of a white underclass.