(2 of 6)

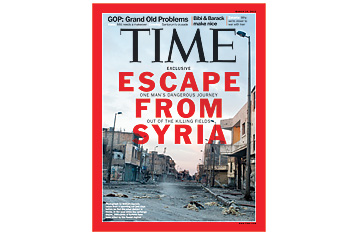

A year ago, on March 6, a group of teenagers in the Syrian town of Dara'a scribbled graffiti on a wall: THE PEOPLE WANT THE REGIME TO FALL--a verbatim echo of the chant that had recently shaken Tunisia and Egypt and led to the demise of ingrown tyrannies. The boys were thrown into jail, an overreaction on the part of the Assad regime that only ensured that the Arab Spring would blow into Syria. Incensed local residents began staging huge and brave protests against the dynasty that has ruled the country since 1970. Demonstrations spread to other cities and were met with vicious reprisals: arrests, torture and killing. The crackdown encouraged a series of military mutinies and defections. Civil disobedience turned into armed struggle. Cities were besieged; the country slipped into war. The U.N. estimates that 7,500 people have been killed so far.

Syria has a particular tradition of keeping massacres private. In 1982 the city of Hama staged an uprising against the government, then ruled by the father of the current President. It was ruthlessly put down with hardly anyone to bear witness to what took place. The consensus is that at least 10,000 died, though some estimates are twice that. It has been hard to know the truth on the ground in Syria even in good times; in bad times it is impossible--and dangerous. Residents of Hama told a TIME reporter on a clandestine visit in August that they know where the bodies are buried but do not dare pray over the grave sites because the regime continues to watch and to punish. To Damascus, mourning--even generations after--is dissent.

But the Arab Spring proved that sunlight can be a revolutionary weapon; government brutality, when filmed and tweeted and posted on Facebook, shames the world into paying attention. Geopolitics also puts Syria in the spotlight: the country sits at the strategic nexus in the fight between the Shi'ite theocracy in Iran and the region's Sunni powers, led by Saudi Arabia. The 21 other members of the Arab League have called on Assad to step down and pressed China and Russia to cut their ties with his regime. Syrian dissidents smuggled Daniels and his colleagues into Homs to make sure the story stayed in the headlines and to try to save the city from Hama's fate. "These journalists are witnesses to this gigantic crime," says Ricken Patel, director of Avaaz, a New York City--based organization that has helped journalists get into Homs. The Syrian dissidents are "really are grateful for their bravery."

The journey into Bab Amr was harrowing. The Westerners had been led in by activists through an old 2-mile (4 km) water pipeline. At 5 ft. 4 in. (160 cm) high, it did not have quite enough room for adults to stand. (Daniels is nearly 6 feet tall.) It also ran under the Syrian army's firing positions. Abandoned by the regime, the tunnel was used by dissidents to transport supplies to the besieged residents of Bab Amr. Couriers crouched on motorbikes would carry medicine and food and perhaps weapons in and wounded Syrians out. But could it be used to transport injured journalists to safety as well? Daniels and Bouvier did not want to try, since the doctor had warned that she could die of a blood clot if she was not moved carefully.