(3 of 3)

Bush learned the next morning that two dozen top officials at Justice and the FBI were about to quit — which would have been "the largest mass resignation in modern presidential history." Cheney says he had "little patience" for the Justice Department threats and makes plain he advised Bush to stand his ground. Bush's own account says with some exasperation that he could not stand by and watch "my administration implode." Without naming Cheney, he writes that he "made clear to my advisers that I never wanted to be blindsided like that again." It is not known whether he ever learned that Cheney had been trying for three months, without telling Bush, to suppress the legal rebellion.

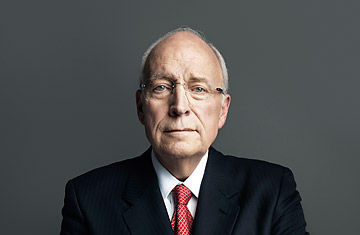

On that day, March 11, 2004, the President of the United States discovered that his Vice President could lead him off a cliff. Their relationship never recovered. Cheney was an antipolitician, prepared to march to his principles at any cost. No President could afford to govern that way.

In the second term, Cheney's memoir becomes a rich account of their mutual disillusionment. He rations his attacks on Bush, laying the President's transgressions at the feet of Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice ("naive," making "concession after concession"), Robert Gates (for telling allies Bush would not bomb Iran) and even Barack Obama, who extended some of the second-term Bush policies that Cheney did not like.

But Cheney makes no serious attempt to disguise the breach. He was "a lone voice," he writes, in favor of bombing a nuclear reactor under construction in Syria with North Korean technology. By Cheney's account, Bush rubbed it in: "Does anyone here agree with the vice president?" he asked in the Situation Room. No one raised a hand.

By late 2006, Bush was making big decisions behind Cheney's back. The President told Cheney he was firing Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, then "turned and was out the door fast." Cheney discovered that Bush's team had been meeting in secret about Iraq, looking for military adjustments that could reduce the political heat on Capitol Hill. The Vice President, who disapproved of "temporizing to placate Democrats," was not invited.

All these, and several more examples he names, are matters of deep distress to Cheney. He soft-pedals the indictment but says Bush's behavior was "out of keeping with the clearheaded way I'd seen him make decisions in the past." The President, in other words, began compromising basic principles for political or diplomatic expedience.

Cheney lashes out with brutal directness about Bush's decision not to pardon Scooter Libby, Cheney's friend and chief of staff, for perjury and obstruction of justice. He tells Bush in private, and the whole world in his book, that the President was "leaving a good man wounded on the field of battle" — a naked accusation of cowardice. Cheney leaves no room for disagreement on the merits. The President sacrificed "doing the right thing" for the trivial pleasure of "positive press about his last days in office."

Here Cheney might have shed a great deal more light. Libby's case arose from a leak that outed a clandestine CIA officer in an opinion column assailing her husband, a harsh Cheney critic. Cheney acknowledges that he was the first to discover Valerie Plame's identity and scribbled out the line of attack later used by columnist Robert Novak: that Plame had sent her husband, Joseph Wilson, on a junket. Libby, who was not Novak's source, testified twice under oath that he did not recall whether Cheney directed him to leak Plame's identity to another journalist. Did the Vice President nudge Libby toward that fateful battlefield? In a chapter devoted largely to the case, he does not say.

Cheney is that rare combination, a zealot and a gifted student of power. Great operators in Washington — Henry Kissinger, say, or James A. Baker — are usually pragmatists. Zealots seldom get near the levers of power. A man with both qualities was bound to leave a mark on history, even if he was reduced in the end to warning of a national-security "train wreck" he no longer had the power to prevent.