(2 of 2)

From the mid-1930s through the late '50s, Time Inc. was probably the largest news organization in the world, with bureaus on every continent. It claimed to reach more than 20 million people each week, and even more during World War II, which the Time Inc. magazines reported on at least as intensely as any other organization. The company's success was partly a result of shrewd management. But it was also a result of Luce, who had looked into the future and seen an increasingly integrated nation bound together by railroads, highways, radio, movies and the rise of a national corporate culture. As a result, Americans would need a vast amount of information and an efficient way of accessing it. Luce embraced that future and created vehicles that served the needs of his rapidly changing times. He had few rivals in the breadth and influence of his empire — William Randolph Hearst, the great newspaper mogul of his time; or William Paley, the founder of CBS; or Lord Beaverbrook, the publisher of newspapers in Britain and beyond; or, more recently, Rupert Murdoch.

By the time Luce retired in 1964, three years before his death, his empire was beginning to show its age. Time Inc. was still thriving, but it was rivaled by television and countless newer magazines. His colleagues prodded him to move into television and branch out into other areas. But Luce, no longer the restless pioneer, tried instead to protect what he had already created — though after his death, his company did indeed expand into electronic media, developing HBO and becoming a major force in cable TV. LIFE, however, had ceased to be profitable by the late 1950s and stopped being published as a weekly in 1972, five years after Luce's death. TIME, FORTUNE and SPORTS ILLUSTRATED have survived and reinvented themselves as the publishing world has changed. But like all magazines and newspapers, they face tremendous challenges.

What would the young, ambitious, innovative Luce have thought about the opportunities that might await him in our own challenging time? Much of what he cared about in his era might seem to him irretrievably lost. For decades, he had worked to portray (and shape) America as a united, common culture. Despite differences in class, race or region, Americans, he believed, shared a basic set of values that transcended diversity. "Nobody is mad with nobody," a LIFE article brightly announced in the 1950s, at perhaps the height of the belief that there was a broadly shared vision of the U.S. In our own fractured and fractious time, such an assumption would find few adherents. But Luce's project of the 1950s and '60s — promoting a vision of a coherent national purpose — is not irrelevant today, despite radical changes in the character of American life.

In other ways, Luce might feel at home now. He was comfortable with diversity. He was an early supporter of racial justice. He was not alarmed by immigration. He welcomed progress and was fascinated by the cultural and technological changes around him. And he believed that all Americans could be educated through the dissemination of knowledge — a project widely embraced today.

One of the most powerful results of the digital age has been the creation of a vast body of new knowledge and information — so vast as to be almost impossible to absorb. A related result has been the fragmenting of that information into discrete communities of knowledge that often reflect individuals' prior beliefs and preferences. Luce, I believe, would resist those trends, just as he resisted similar ones decades ago, and would seek ways to use the tools of technology to broaden, not fragment, a national culture.

Luce was, above all, in search of vehicles of change. He had no fear of the new, and he welcomed it throughout most of his life — modern art (which he once had loathed), modern technology, modern design and modern business (he was always attracted to the most creative and progressive business leaders and considered himself one of them). For all his political conservatism, he was a man in search of the future.

In our time, he would face both the seemingly intractable problem of making money from digital information and enormous competition from thousands of individuals and organizations trying to respond to those new challenges. But Luce — for all his flaws — was an innovator, a visionary and a man of vast and daunting self-confidence. Were he to live in our time, trying once again to revolutionize the spread of knowledge, he might find his talents much in demand.

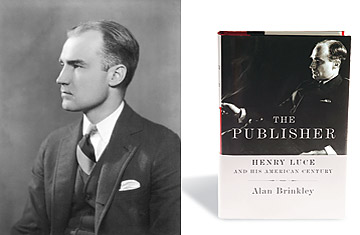

Brinkley is the Allan Nevins Professor of History at Columbia University and author of The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century (Knopf; 2010)