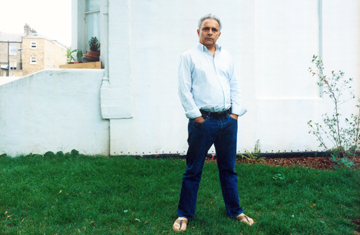

Novel revolution Kureishi has become the poster boy for post-colonial fiction

When the Queen made Hanif Kureishi a Commander of the British Empire in 2008, she gave him a medal embossed with the logo: "For God and Empire." "You can't get better than that," the writer quipped at the time. "The only causes are the lost causes — or the nonexistent ones."

But God and Empire — and the shadows they have cast over Britain — have been very good to Kureishi, providing him with two rich seams of material for his fiction. "When I was a kid, people were always talking about the death of the novel," he says, sitting in a café near his home in London's Shepherd's Bush. "But ever since [Salman Rushdie's 1981 novel] Midnight's Children, it's been terrifically lively. There's been a revolution in writing in the West. And that's thanks to colonialism."

And to Kureishi himself. For a quarter-century his films, plays and novels have captured the motley qualities of post-colonial Britain — its Karachi-born taxi drivers, jack-booted skinheads, coked-up admen and firebrand mullahs. His latest work, now playing at London's National Theatre, dramatizes his 1993 novel The Black Album. Set in 1989, during the furor over Rushdie's The Satanic Verses, it follows a British Pakistani college boy torn between the delights of sex and Western culture and the lure of Islamic fundamentalism. The book is a fresh and funny bildungsroman, capturing an antic '80s London. Sadly the play is clunky and shallow, flattening its characters to the very stereotypes that Kureishi's better work has helped explode. The reviews were a bit "rough," admits Kureishi, but that's life as a writer: "You've got to take risks, do weirdo stuff."

Back in the early 1990s, when Kureishi first started going to extremist London mosques for research for The Black Album, scribbling down notes at Friday sermons was weirdo stuff indeed. Today, with London still scarred from the 2005 bombings by British-born terrorists and the far-right British National Party winning seats in recent European parliamentary elections, the novel seems spookily prescient. Though its themes of radical faith and alienation endure, Kureishi's mosque visits didn't. One Friday, he recalls, the mullah at a mosque in London's East End warned that "there are spies and journalists in our midst," after which Kureishi was tossed out "by four blokes, who picked me up and heaved me out the door."

Kureishi has been attracting controversy since his Oscar-nominated screenplay for 1985's My Beautiful Laundrette, about a young, gay British-Pakistani making it — and making out — in Thatcherite London. The discovery that he could shake things up was wonderfully liberating, particularly for the son of a Bombay intellectual stuck commuting from a dreary London suburb to work as a civil servant in the Pakistani embassy. "My parents' generation were immigrants, who nobody noticed, and who didn't want to be noticed," he says. "Then came my generation." The boy who was called "Pakistani Pete" by a teacher for whom all South Asians — even those, like Kureishi, born in Britain to an Indian father and an English mother — were Pakistanis, and whose friends went out on weekends looking for brown-skinned people to beat up, spun his anger into art. While other children of immigrants tried to create an identity through cast-iron faith, Kureishi forged his through rebellious fiction. His works were a mosh pit of high and low Western culture, with knowing references to Wittgenstein and Genet, ecstasy raves and gay sex. Suddenly, Asian Britain wasn't just about corner shops, victimhood and longing for Bombay, but anarchy in the U.K.

Where Rushdie, by now a friend, used baroque language to spin fantastical tales spanning continents and centuries, Kureishi stayed street. His father figures were faded and refined — dusty relics from a more gracious time who looked to literature or socialism to block out the cold realities of being foreign-born in 1970s Britain. Their sons weren't Pakistanis but "Pakis," who snorted coke, fornicated and embraced the Thatcherite dream of making money fast. "When I was in school, the long-standing stereotype of the South Asian male was of the studious nerd, who was going straight to an enviable university to make his parents proud," novelist Zadie Smith tells TIME in an e-mail. "But a lot of the second-generation kids ... we weren't planning on becoming accountants. We wanted to get stoned, get laid and be cool, like everyone else. When I was 15, Kureishi was the only writer I'd ever read who seemed to be aware of this huge British demographic. He wrote about us not as if we were exotica, but simply as a self-evident part of British life."

At 55, Kureishi is a tidy man, his shirt buttoned, his gray curls — and his sentences — clipped. He was "very pleased and flattered" by his CBE and extols a recent stint teaching at Yale as "very comfy." But his spot in the cultural establishment is proof that his revolution succeeded. He's about to start on the screenplay of The White Tiger, the Booker Prize winning novel by Indian author (and occasional TIME contributor) Aravind Adiga. That a story about a poor Indian hustling his way in Bangalore sold millions of copies all over the world, notes Kureishi, shows that post-colonial fiction has reinvigorated the novel.

Bart Moore-Gilbert, professor of post-colonial literature at London's Goldsmiths College and author of a book on Kureishi, places the writer in the tradition of Dickens and H.G. Wells, with their "old-fashioned concern with the condition of England." Especially when that condition changes. Kureishi says the Muslims his sons go to school with aren't attracted by extremism. Islam is "what it was for people when I was a kid — a quarter of their lives," he says. "You're a soccer fan, you go shopping, watch TV and you're a Muslim." The England Kureishi chronicles — indeed, helped create — is a country where Islam, curries and brown skin have become as British as Earl Grey tea and rain.