On the morning of Feb. 19, 1979, a Cessna 172 took off from Santa Monica, Calif., bound for the ski resort Big Bear. On board were Norman Ollestad, his father, his father's girlfriend Sandra and the pilot. Crossing the San Gabriel Mountains in heavy gray snow clouds, the plane failed to clear Ontario Peak. It crashed into the mountain at 8,200 ft. (2,500 m), just short of the summit, in the middle of a blizzard. Norman and Sandra survived the initial impact, but only Norman made it down off the mountain. He was 11.

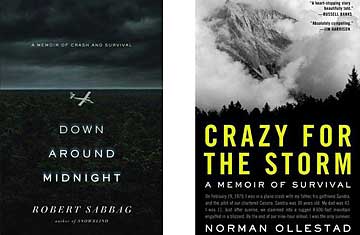

Your chances of being involved in a plane crash are pretty slim. By some estimates, they're as low as 1 in 11 million. But should you live through one — possibly as a gesture toward cosmic compensation — your shot at a book deal goes way up. There are two new memoirs out by survivors of plane crashes: Ollestad's Crazy for the Storm (Ecco; 272 pages) and Robert Sabbag's Down Around Midnight (Viking; 214 pages). Starbucks has picked Ollestad's memoir for its book program, and you can see why: plane crashes are usually unknowable, secret events. We may never find the black box from Air France Flight 447, lost off the coast of Brazil on June 1. But from these crashes, we have something even better.

Before he survived the crash, Ollestad had to survive his childhood. His father was a dashing adventurer who pushed his son to feats of preadolescent derring-do as a surfer and skier that are unimaginable by today's nurturing parental standards. It may have been his familiarity with physical danger, and his calmness in the face of it, that saved Ollestad on Ontario Peak. It helped him manage the psychic aftermath too, to put a frame around it. To the Ollestads, life was "raw and wild and wonderfully unpredictable." To be paralyzed by fear of it, by the inevitability of pain and loss, would be the real tragedy.

Sabbag was even unluckier than Ollestad, if that's possible. In 1979 — four months after Ollestad's crash — Sabbag was on an Air New England flight that went down in a trackless forest just short of the airport on Cape Cod. There was no warning. "I breathed in," he remembers, "and when I breathed out I was pulling six Gs." His back and pelvis snapped on impact. He survived — along with the co-pilot and the other seven passengers, though not the pilot — and even learned to walk again. But he never escaped a sense that his life had been broken neatly in two at that moment. In Down Around Midnight, Sabbag seeks out his fellow travelers in an attempt to figure out exactly what happened that night — and what it meant.

Sabbag is more of a writer than Ollestad. At the time of the crash, he was already a published author, and he has a knack for thumbnail portraits and sardonic humor, whereas Ollestad's prose has a more breathless, unpolished, confessional quality. But Sabbag's book, while more eloquent, is less complete. If there is a tragedy in Down Around Midnight, it is not of the Greek kind — Sabbag's bad luck was purely random, and if there was a fatal flaw involved, it wasn't his. He circles and circles around the trauma, interviewing his fellow victims, and their relatives, and even the emergency workers who beat a trail through the woods to save them. But he never arrives at an epiphany big enough to match the magnitude of what happened to him — the terrible secret remains a secret even from him. Like the flight he took that fateful night, Down Around Midnight is a journey that ends before it reaches its destination.