As explicit discrimination has receded in recent decades, those who study prejudice have had to grapple with a difficult question: Why do some minority groups continue to perform worse than others on academic tests as well as in social measures like income and job status? Has bias merely become better hidden, or are other forces at work?

One theory that has emerged from psychology departments in the past few years is that members of stigmatized groups lag behind others partly because they have internalized the stereotypes. Some minorities, the theory goes, do worse in academic and other settings merely because they expect to do worse. Their negative expectations produce stress and interfere with cognition.

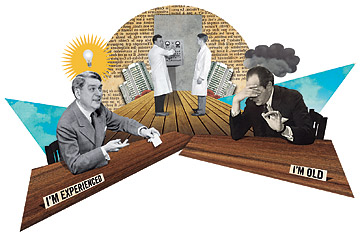

Since 1995, when Stanford psychologist Claude Steele (brother of Shelby) and his student Joshua Aronson started referring to this phenomenon as "stereotype threat," dozens of studies have confirmed that African Americans, girls and even college jocks are susceptible. A new study published in the journal Experimental Aging Research shows that older people can also become victims of their own low expectations. Psychologists at North Carolina State University, in Raleigh, recruited 103 people ages 60 to 82 to perform recall tests. Researchers told about half the participants that the purpose of the tests was "to examine the effect aging has on memory." The others were told the tests had been written to correct for age-related bias. Those in the first group performed significantly worse than those whose internalized stereotypes hadn't been triggered. Interestingly, participants ages 60 to 70 were significantly more vulnerable to stereotype threat than those 71 to 82.

The authors theorize, persuasively, that baby boomers are more sensitive about losing their sharpness than those more accustomed to the vicissitudes of advancing age.

What can we do about stereotype threat? Research has found that positive stereotype reinforcement is as powerful as the negative variety. In a recent study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Indiana University psychologists found that even after the "women are bad at math" canard is introduced, women's performance on math tests doesn't suffer as long as a compensating positive (and also specious) stereotype--"college students are good at math"--is presented at the same time.

The most practical solution to stereotype threat is an early intervention: stop asking students for demographic information right before they take important standardized tests. Baruch College psychologist Catherine Good, who helps run reducingstereotypethreat.org says many states collect race and gender data just before kids start filling in ovals. "Move those questions to the end," she advises, and stereotypes won't be a threat in the first place.