In early February, Casino Mogul Steve Wynn took a stand on layoffs. The gaming industry is flailing — Nevada regulators recently formed a task force on bankruptcies — but when it came to cutting costs by cutting employees, Wynn wouldn't hear of it.

Instead, Wynn announced that everyone at his company's two Las Vegas properties, Wynn and Encore, would take a pay cut. Salaried workers earning $150,000 or more would see a 15% drop in their paychecks; those making less would take a 10% hit. Hourly employees would go from a 40-hour to a 32-hour week. The idea: save millions of dollars without putting anyone out of a job while maintaining the service level at the luxury hotels. "We don't want anybody on unemployment here," Wynn said at the time, "or without insurance." (See 10 things to buy in a recession.)

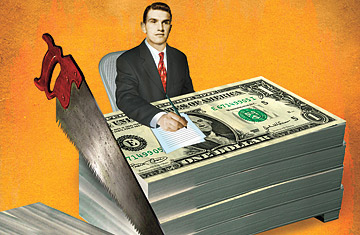

Let's hope it works. Pay cuts to avoid layoffs have become increasingly popular in corporate America. It's a choice that oozes compassion (never mind that many of these pay cuts become permanent) and keeps companies poised to quickly scale operations back to full force when the economy rebounds. But that's a big contingency, one that firms trying to do the right thing for both workers and shareholders are starting to trip over.

In December, FedEx announced that its senior executives would earn 7.5% to 10% less, while its U.S.-based salaried workers would take a 5% haircut — affecting 36,000 people. "But even these measures," CEO Fred Smith said in a message to employees, "may not be enough to offset the rapidly deteriorating economy that has hit our industry so hard." In early April, the company let go of 1,000 employees.

And that's problematic. One reason companies opt for pay cuts is to preserve worker morale, but that can be a delicate thing. "Initially, this sounds really good to people because we're all chipping in. It's almost like in World War II when housewives bought organ meat instead of steaks and chops to save meat for the boys," says Mitchell Lee Marks, a professor at San Francisco State University's College of Business. "There's a sense of camaraderie and loyalty. But what if you don't win the war? Then why did we do that?"

Preserving jobs — even if the alternative is losing them — can be demoralizing in certain ways too. For top execs, a cut may mean it's time to dial back on the trips to St. Bart's. For line workers, who've probably calculated exactly how much mortgage and college tuition they can afford based on their salaries, the effect is more jarring. (See 10 things to do in Las Vegas.)

When Acco Brands, an office-supply company that makes products like Swingline staplers, imposed a massive 47% pay cut for six weeks, it established an emergency-loan program for employees who couldn't make ends meet on a shrunken paycheck. "It impacts standard of living," says Truman Bewley, an economist at Yale who has studied the ways companies cut back during recessions. "People don't quickly forget a pay cut."

Potential pitfalls aside, the number of companies that are slashing paychecks is rising. According to a survey of 245 large U.S. companies by the human-resources consultancy Watson Wyatt, 5% of firms had reduced salaries by December. In February that figure was up to 7%. And the proportion of companies shortening the workweek — a way to cut overall pay for hourly employees — jumped to 13%, from 2%. "Six months ago, all the questions I got were about severance," says Steve Gross, who runs the employee-compensation consulting group for the HR outfit Mercer. "Now — including twice today — I'm getting questions from companies saying, We want to reduce wages, and we're thinking of reducing hours." (Read "As Layoffs Mount, Severance Packages More Negotiable.")

That shift — and a drop in the number of companies telling Watson Wyatt they're planning layoffs — could lead a person to take a rosier view of the economy. "At some point, we're going to emerge from this recession, and companies know they need to emerge with some sort of staff," says Laura Sejen, head of Watson Wyatt's strategic-compensation group.

Less optimistically, firms might be realizing they've let go of so many already, more cuts would hit bone. Also, reducing paychecks during a recession can provide cover for companies that had been looking to trim labor costs anyway. But maybe we should hope for purer intentions. And that the plan for avoiding layoffs works.