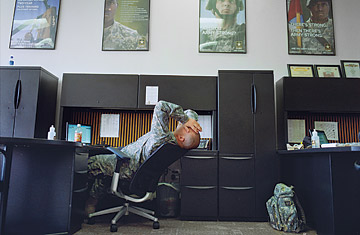

The Nacogdoches, Texas, recruiting office where Larry Flores and Amanda Henderson worked

(4 of 4)

Flores, 26, was told his failure as a station commander meant he'd soon be returning to a basic recruiter's slot. "He was an emotional wreck," said a soldier who spoke with him the evening of Aug. 8. "He said he felt he failed as a station commander," the colleague told investigators. "He had asked me for a firearm. I told him I didn't have one. It actually never crossed my mind that it might have been for himself." Flores hanged himself that night. "The leadership is the major cause for SFC Flores taking his own life, he was a prideful soldier," a fellow station commander wrote in a statement, carefully noting Flores' posthumous promotion. "I believe this was a snap decision because SFC Flores stated to me that he grew up without a father and he would never do that to his kids."

Amanda Henderson had worked alongside Flores in Nacogdoches. Her husband, Sergeant First Class Patrick Henderson, 35, served at a recruiting office 90 minutes away in Longview. Patrick met Amanda at recruiting school after a combat tour in Iraq, and they married in January 2008. With their new jobs, though, "there was no time for family life at all," Amanda says. While Patrick didn't want the assignment, his widow says, the Army told him he had no choice. He masked his disappointment behind a friendly demeanor and an easy smile.

But things got worse after Flores' death. "He just kept saying it was the battalion's fault because of this big bashing session that had taken place" six days before Flores killed himself, Amanda says. "I can't tell you how mad he got at the Army when Flores committed suicide." Two weeks later, Patrick spoke of killing himself and was embarrassed by the fuss it kicked up. "He started to get reclusive," Amanda says now.

"He sounded pretty beat up," a fellow recruiter told investigators later. "He seemed to be upset about recruiting and didn't want to be out here." Patrick was taken off frontline recruiting and assigned to company headquarters. But it didn't stop his downward spiral. The day after a squabble with his wife on Sept. 19, Patrick hanged himself.

A Senator Demands Answers

It wasn't until reports in the Houston Chronicle provoked Republican Senator John Cornyn of Texas to demand answers that the Army launched an investigation into the string of suicides. "It's tragic that it took four deaths to bring this to the attention of a U.S. Senator and to ask for a formal investigation," Cornyn says. After Cornyn began asking questions, the Army ordered Brigadier General F.D. Turner to investigate. Recruiters told him that their task is a "stressful, challenging job that is driven wholly by production, that is, the numbers of people put into the Army each month," Turner disclosed Dec. 23 after a two-month probe.

The report found that morale was particularly low in the Houston battalion. Its top officer and enlisted member — Lieut. Colonel Toimu Reeves and Command Sergeant Major Cheryl Broussard — are no longer with the unit. (He left for another post in USAREC; she was removed from her post until an investigation into her role is finished, and she is working in the San Antonio Recruiting Battalion.)

In an interview, General Turner would not discuss the personal lives of the victims, but his report noted that all four were in "failed or failing" relationships. Yet he conceded that "the work environment might have been relevant in their relationship problems." The claim of a failing relationship is denied by Amanda Henderson and by testimony from fellow recruiters. And an Army crisis-response team dispatched to Houston in October to look into last summer's two suicides cited a poor work environment — not domestic issues — as key.

After Turner's report, Lieut. General Benjamin Freakley, head of the Army Accessions Command that oversees USAREC, asked the Army inspector general to conduct a nationwide survey of the mood among Army recruiters. The Army also ordered a one-day stand-down for all recruiters in February so it could focus on proper leadership and suicide prevention. The worsening economy is already easing some of the recruiters' burden, as is the raising of the maximum enlistment age, from 35 to 42. But with only 3 in 10 young Americans meeting the mental, moral and physical requirements to serve, recruiting challenges will continue.

Amanda Henderson, who lost both her husband and her boss to suicide last year, has left that battlefield. "The Army didn't take care of my husband or Sergeant Flores the way they needed to," she says. Though still in the Army, she has quit recruiting and returned to her former job as a supply sergeant at Fort Jackson. Because of the poor economy, she says, she plans to stay in uniform at least until her current enlistment is up in 2011. "Some days I say I've just got to go on," she says. "Other days I'll just sit and cry all day long."