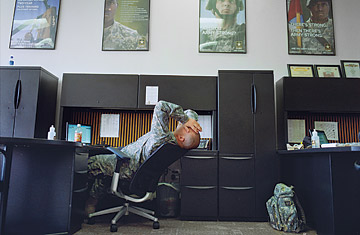

The Nacogdoches, Texas, recruiting office where Larry Flores and Amanda Henderson worked

(2 of 4)

The military isn't known for treating underperformers with kid gloves. But the discipline can be harder for recruiters to take because they are, in most cases, physically and socially isolated. Unlike most soldiers, who are assigned to posts where they and their families receive the Army's full roster of benefits, 70% of Army recruiters live more than 50 miles (80 km) from the nearest military installation. Lacking local support, recruiters and their spouses turn to Internet message boards. "I hate to say it, but all the horror stories are true!" a veteran Army recruiter advised a rookie online. "It will be three years of hell on you and your family." One wife wrote that instead of coming home at the end of a long workday, her husband was headed "to Super Wal-Mart to find prospects because they're open for 24 hours."

Today's active-duty Army recruiting force is 7,600-strong. Soldiers attend school at Fort Jackson, S.C., for seven weeks before being sent to one of the 38 recruiting battalions across the nation. There they spend their days calling lists of high school seniors and other prospects and visiting schools and malls. At night, they visit the homes of potential recruits to sell them on one of the Army's 150 different jobs and seal the deal with hefty enlistment bonuses: up to $40,000 in cash and as much as $65,000 for college. The manual issued to recruiting commanders warns that, unlike war, in recruiting there will be no victory "until such time when the United States no longer requires an Army." Recruiting must "continue virtually nonstop" and is "aggressive, persistent and unrelenting." (See more about the military.)

Lone Star Losses

Nowhere has the pace been more punishing than inside the Houston Recruiting Battalion. One of every 10 of the Army's recruits last year came from Texas — the highest share of any state — and recruiters in Harris County enlisted 1,104, just 37 shy of first-place Phoenix's Maricopa County. The Houston unit's nearly 300 recruiters are spread among 49 stations across southeast Texas. Since 2005, four members recently back from Iraq or Afghanistan have committed suicide while struggling, as recruiters say, to "put 'em in boots." TIME has obtained a copy of the Army's recently completed 2-inch-thick (50 mm) report of the investigation into the Houston suicides. Its bottom line: recruiters there have toiled under a "poor command climate" and an "unhealthy and singular focus on production at the expense of soldier and family considerations." Most names have been deleted; the Army said those who were blamed by recruiters for the poor work environment didn't want to comment. While some recruiters were willing to talk to TIME, most declined to be named for fear of risking their careers. (See pictures of U.S. troops' 6 years in Iraq.)

Captain Rico Robinson, 32, the Houston battalion's personnel officer, was the first suicide, shooting himself in January 2005. But one of his predecessors, Christina Montalvo, had tried to kill herself a few years earlier, gulping a handful of prescription sleeping pills in a suicide attempt that was thwarted when a co-worker found her. Montalvo says a boss bullied her about her weight. And she was shocked by the abuse that senior sergeants routinely levied on subordinates. "I'd never been in a unit before where soldiers publicly humiliated other soldiers," says Montalvo, who left the Army in 2002 after 16 years. "If they don't make mission, they're humiliated and embarrassed."

Several months after Robinson committed suicide, Staff Sergeant Nils Aron Andersson arrived in Houston as a recruiter. Andersson had served two tours in Iraq with the 82nd Airborne and had won a Bronze Star for helping buddies pinned down in a firefight. "I asked him what he did to get it, and he just looked right at me and said, 'Doing my job, Dad, just doing my job,' and that's all he ever said," says his father Robert of Springfield, Ore. "He wouldn't talk to me about Iraq."

Aron, as he was known, had changed in Iraq. Perhaps it was the September 2003 night he gave up his exposed seat in a Black Hawk helicopter to a younger soldier who wanted the thrill of sitting there and who ended up being the only one killed when the chopper flipped on takeoff. Or maybe it was the day Andersson's squad had to destroy a speeding suicide van headed straight at their checkpoint, despite the women and children inside.

Instead of returning for a third tour, Andersson chose recruiting. He trained at Fort Jackson, filed for divorce and joined the Houston battalion in 2005. "They were working the crap out of him," Robert says. "I'd get calls from him at 9:30 at night — 11:30 in Houston — and he'd say he was just leaving the recruiting office and starting on his 40-minute drive home." His easygoing son also developed a hair-trigger temper during his time at the River Oaks and Rosenberg recruiting stations. "He wasn't really a salesman," Robert says, "and recruiters are trying to sell something."