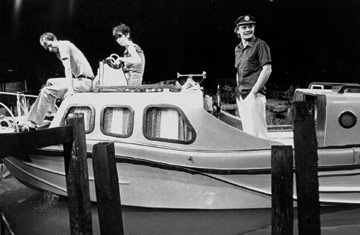

WAY UPSTREAM: The stage was filled with water for Ayckbourn's ambitious 1981 play

The proprietor of the little Scarborough hotel where I was staying — a maternal Scottish woman who apologized sweetly for the lack of Internet service — stopped by my breakfast table to ask what I thought of the play I'd seen the previous night. "It's one of Alan's, isn't it?" she said. Then, after hearing my favorable review, she added a bit wistfully: "I don't know what we'll do when he retires completely. It won't be the same without him."

In Scarborough, everyone knows who Alan is. Playwright Alan Ayckbourn was an 18-year-old actor when he first came to this resort town on the coast of North Yorkshire, England, in the 1950s and joined a theater company run by Stephen Joseph, Britain's pioneer of theater-in-the-round. After starting to write his own plays, then working as a radio-drama producer for the bbc, Ayckbourn returned to Scarborough, where in 1972 he became artistic director and chief playwright-in-residence for what is now called the Stephen Joseph Theatre. It is there that nearly all of his 70-plus plays have premiered, in productions usually directed by Ayckbourn. Many of them — starting with comedies such as How the Other Half Loves and Absurd Person Singular — have then moved on to long, successful runs on the West End, and beyond.

That, at least, was the pattern until a few years ago, when Ayckbourn's run of hits grew spotty, and he had a fight with the London producers of his 2002 trilogy Damsels in Distress. (He wanted the plays to be staged in repertory, but after mixed reviews, the producers dropped most performances of the two weaker shows.) Then, in February 2006, Ayckbourn's machine-like productivity was interrupted by a serious stroke. He was back to directing within several months, but in June 2007 he announced that he would step down as artistic director of his Scarborough theater at the end of this year, to concentrate on writing and directing his own work.

He's getting a big send-off. Over the summer, the Stephen Joseph Theatre showcased three of Ayckbourn's supernatural plays: revivals of the spooky Haunting Julia and Snake in the Grass, and the world premiere of the more comic Life and Beth. Following them this month is a revival of his 1985 tragicomedy Woman in Mind, and, in December, the premiere of his new musical, Awaking Beauty. Meanwhile, the Old Vic theater is welcoming Ayckbourn back to London with a revival of his most celebrated work, The Norman Conquests: his 1973 trilogy about a traumatic family weekend, with each play covering the same time period from a different room in the family's country house.

All of which, one hopes, will spark a fresh reappraisal of the work of the most misunderstood, and very likely best, playwright currently writing in English. That is far from a widespread view. In America, Ayckbourn is still typecast, anachronistically, as a lightweight boulevard farceur (the "British Neil Simon"), or simply as a clever deviser of staging gimmicks: plays that squeeze the action in several rooms into one space, or move backward in time, or fill up the stage with water, or (in his insanely ambitious Intimate Exchanges) have no fewer than 16 dramatic permutations, depending on which alternative action the characters take in several key scenes.

Even in his own country, Ayckbourn has never received the critical respect accorded contemporaries like Tom Stoppard and David Hare. They write "important" plays about political issues or world-famous physicists or 19th century Russian philosophers. Ayckbourn's realm is smaller and more familiar — the domestic and romantic predicaments of modern, middle-class Brits. Yet no one has probed more acutely, or with a finer balance of laughter and pain, the sad human drama behind these tidy surfaces: the inability of people to connect, to see the casual cruelty they inflict on others, to come to terms with their failed illusions, to be happy. A woman's spoofy fantasies of a perfect domestic life turn into the chilling symptoms of her descent into madness in Woman in Mind. A charming, well-intentioned "golden couple" manage inadvertently to destroy the lives of nearly everyone they come in contact with in Joking Apart. A holiday boat excursion for two landlubberly married couples turns into a fascist parable in Way Upstream.

That delicate mix of comedy and tragedy is something Ayckbourn hit upon almost from the beginning. "When I started in weekly rep, we did a different play every week," he says. "I became aware of a pattern that was evolving — we would do a comedy, then a thriller and then a serious play. With the comedy, all the lights came up to full. And everyone was very, very loud and terribly fast. And in the serious plays, it was positively dark, and everyone was talking very quietly. And I thought, I'd love to write a very, very slow comedy, with none of the lights on. And then I'd write a very bright tragedy, with lots of lights."

Ayckbourn, 69, is explaining this in the sunny and spacious Scarborough house (actually three Georgian townhouses that he connected) where he lives with his second wife, former actress Heather Stoney. The effects of his stroke are visible. He walks unsteadily, and his left hand is fairly useless, reducing his two-finger typing method to just one. Yet his speech and mental acuity are undiminished. ("My head's working fine," he says — though "I still have a problem with a group of people, if they're all talking at once.") He laughs frequently, dives into anecdotes with an actor's relish and a repertoire of spot-on accents, reminisces good-naturedly about the "worst night of my life," when he was rushed to the hospital. "I lost the use of the leg very quickly, and the arm followed overnight," he says. "I was getting really scared. I thought, my God, what else is going to go off?"

He had some trepidation about returning to writing. But once he plunged in (Life and Beth is his first post-stroke work), he found it came as easily as before. Ayckbourn writes quickly, typically barreling through a complete draft in 10 days. "My attitude with plays is they're like pictures, in a sense," he says. "You have to write them in the frame. If you stop in the middle of a picture, I imagine, leave it for several weeks and start again, you're going to get a lopsided composition. Some of my best writing comes from serendipity. [Unexpected] things drop in."

Ayckbourn, whose father played violin for the London Symphony Orchestra and whose mother wrote novels, was influenced in his early years less by theater than by the triple bills of American B-movies that he would spend long afternoons watching. Even today he seems aloof from most of his British playwriting peers; he's friends with few of them, and the only dramatist with whom he professes a close affinity (personal and professional) is Harold Pinter, who directed him in an early production of The Birthday Party. "I got fascinated by his use of dialogue, his use of words, the structure of sentences," Ayckbourn says. "You can see even now what's actually rubbed off on me from him."

At a time when playwrights like Stoppard, Hare and Michael Frayn are wrestling with weighty topical issues, Ayckbourn admits to having little interest in politics: "I've lived through enough times to know, as the French say, plus ça change — nothing changes, give or take the odd Iraqi war." One thing that musters his outrage, though, is the dwindling government funding for the arts, which has endangered local theaters like his Scarborough company — where, in all his years as artistic director, he has never taken a salary. "My salary is in the accounts," he says, "but it usually goes flying out to pay for some damn trapdoor or something."

Indeed, it's those populist, regional roots that helped shape Ayckbourn's aesthetic: his commitment to exploring serious and subtle themes without abandoning his primary job of keeping an audience entertained. "I grew up in this little town writing for a theater that relies entirely on its audience to survive," he says. "It's not just a matter of making them laugh. It's giving them a reason to want to stay in the theater." He's been able to keep them in the theater with less apparent effort than almost anyone writing today. And even if the folks in Scarborough may see a little less of him, he doesn't plan on stopping any time soon.