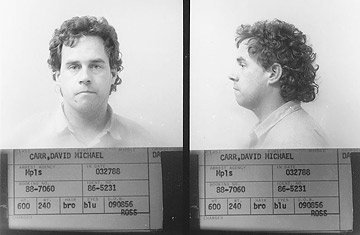

Carr under arrest in 1988

Every memoir is in one sense an argument--a writer's version of his or her past. But, as readers who cashed in their debunked copies of A Million Little Pieces know, recent memoirs have been just as notable for the arguments they raise about the intersection of fact, truth and memory.

In The Night of the Gun (Simon & Schuster; 389 pages), his arresting story of addiction and recovery, David Carr takes on these issues by trying to pre-empt them. Carr, an ex--crack addict turned media columnist for the New York Times, faces two problems in writing his story: he was so often high during the period in question that he's fuzzy on the facts, and he's writing in the post--James Frey era, when being fuzzy on the facts can land you in the hot seat on Oprah.

Attuned to these and other pitfalls of inaccuracy (he was friends with Jayson Blair at the Times), Carr sets out to "report" his memoir, which is to say he digs up his medical and police files and conducts some 60 interviews with people who knew him then and know him now, from his parents to his rehab counselors to his grownup twin daughters. Wary of painting a distorted self-portrait, he offers up a researched composite instead.

The book begins with Carr sitting opposite his editor at a Minneapolis business magazine, being given a choice between quitting drugs and getting fired. He picks the latter and promptly goes on a bender--a long, violent night that ends, as he recalls it, with him on the wrong end of the barrel of a gun. It is March 1987, and Carr is 30 years old. He has been doing cocaine for nearly a decade, and another year and a half will elapse before he goes in for his fifth and final detox.

The opening scene, with its choice of desk or drug habit, introduces one of the book's most unsettling truths: that despite Carr's recollection that he cleaned up his act to care for his newborn daughters, the more compelling factor was his professional ambition. Much of the memoir's emotional heft involves Carr's coming to terms with this idea, realizing that for him, work is, "in some twisted way, more sacred, more worthy of protection, than friends, loved ones, and family."

As far as this book goes, the investment pays off. Carr's voice is persuasive; he not only anticipates every potential critique of his project but also hurls each one fiercely at himself. Don't bother telling him that he's a presumptuous navel gazer for pursuing this story; he knows it. When he visits his ex-wife Kim, on whom he recklessly cheated, she refuses to talk with him about the past. It's a satisfying encounter, as we witness the head-on collision of Carr the intrepid reporter-author and Carr the self-critical and ambivalent subject. Kim's silence, he writes, "is a significant loss in the effort to find the truth of what I did and why. But I secretly admired her unwillingness to engage my needs, my narcissism, one more time."

An old friend, Ralph, throws a different kind of stumbling block his way. "I don't know," says Ralph, when pressed for the details of a drunken fracas in which he and Carr were involved. "You're asking one guy who is drunk and stoned if his memory matches the other guy's who's drunk and stoned."

These testimonies show that as a truth-seeking mechanism, Carr's approach is not foolproof. And it does have its narrative drawbacks. The story starts out choppy, moving back and forth within each brief chapter from Carr on crack to Carr manning the video camera. The chronological jumps cause some repetition, and Carr is not immune to the tic of capping off his vignettes with a punch line, which works better in a magazine than in a book.

Not surprisingly, though, the pace relaxes when Carr reaches his recovery stage; by that point, familiar with the major players and milestones in his life, the reader can relax too. And if he lapses into clichés on occasion (he adores his daughters "madly, deeply, truly"), at other times his word choice attains a chilling precision, as when he describes the two girls on the date of their premature birth: "They weighed a bit more than a kilo, a term of art in our current context." Carr and the girls' mother had used crack during her pregnancy--he had just handed her a pipe when her water broke--and it is both horrifying and apt to hear the babies quantified on the same scale as a brick of cocaine.

It's in moments like that one--when coke and kids mix, brought together in Carr's life and his language--that you realize how successfully he has woven his tale. If the reporting device started out as a "fig leaf," to keep him from obsessing about "adding to a growing pile of junkie memoirs," it doesn't end up that way. The Night of the Gun is in part a writerly exercise in defense and disarmament--memoir in the throes of an existential crisis. But that does not prevent it from being a great read. This is largely because, in using his reporter's chops to investigate his own past, Carr taps the very skills that propelled him to survive. His method, as much as his madness, is the story.