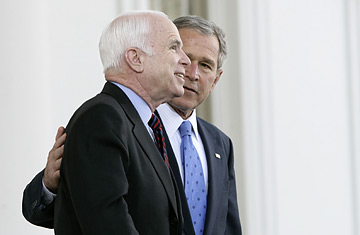

Republican U.S. presidential nominee Senator John McCain is greeted by U.S. President George W Bush at the Rose Garden at the White House on March 5, 2008.

It was in Portsmouth, Ohio, the other day when a supporter neatly summed up the obstacle lying between John McCain and the White House. "When," the young man implored, "are you going to go out and say, 'Read my lips. I am not the third term of Bush'?"

In a business of bitter rivalries and awkward alliances, few political relationships have been more bitter, awkward or downright tortured than John McCain's eight-year entanglement with George W. Bush. After their nasty 2000 battle for the GOP nomination, McCain's differences with Bush were so numerous and so deep that in 2001 he discussed with top Democratic leaders quitting the Republican Party. Three years later, McCain remained so estranged from the White House that John Kerry begged him to run with him on the Democratic ticket against Bush. Even though their rapprochement in 2004 drained some of the bile from their relationship, the two men have never been friends. At best, theirs is a partnership sustained by the benefits each has conferred on the other and a grudging admiration each has for the other's toughness.

McCain's embrace of Bush helped him emerge as the GOP nominee this year from a crowded field of flawed candidates. But it came with a steep price, for his ties to the President now act like leg weights in his race against Barack Obama. They make it possible for Democrats to argue that a vote for McCain is a vote for more of what the country has endured over the past eight years.

This, despite the fact that on campaign finance, tax cuts, health care, judicial nominations, the environment, the use of torture, the fate of Guantánamo Bay and other issues, McCain stood apart--and sometimes alone--from both his President and his party. For all that, he cannot escape Bush's shadow--in part because no Republican nominee could but also because McCain cannot afford to try, given how suspiciously he is regarded by conservatives. And so he answers questions like that one in Ohio with a fatalistic admission that he and the President are linked, for better and probably for worse. "Bush could beat him twice," says a friend who knows McCain well. "Imagine how bitter he feels."

The Crucible

John S. McCain and George W. Bush grew up in tandem, both favored, third-generation sons of prominent Washington families, accustomed to power and influence. Both were poor students and merry pranksters, and both had reputations as drinkers as young men. But the Vietnam War marked a critical divergence: McCain entered Annapolis and wound up spending five years in a Hanoi prison camp, and Bush avoided the war by landing a coveted spot in the Texas Air National Guard. McCain was launched into politics by his heroism, Bush by his gold-star political name. Partly because of their age difference (Bush is a decade younger), and partly because Bush got a late start in the game, their paths had rarely crossed before they ran against each other for the Republican presidential nomination in 2000.

After he upset an overconfident Bush by 19 points in New Hampshire, it appeared that McCain might take South Carolina too, ending Bush's bid. In a Greenville, S.C., hotel room the day after his New Hampshire loss, Bush's high command agreed to attack McCain as a double-talking Washington insider and closet liberal. They also discussed the help they could expect from outside groups not legally permitted to coordinate with the campaign. Said a Bush adviser: "We gotta hit him hard."

They did. While the campaign itself launched a fusillade of negative attacks, a network of murky anti-McCain groups ran push polls spreading lies about McCain's record. They papered the state with leaflets claiming, among other things, that Cindy McCain was a drug addict and John had fathered a black child out of wedlock, complete with a family photograph. The dark-skinned girl in the photo was, in fact, the McCains' daughter Bridget, whom they adopted as an infant after Cindy met her on a charity mission at Mother Teresa's orphanage in Bangladesh. It was, even by GOP standards, unusually foul stuff.

Up to that point in the campaign, McCain had been more or less ambivalent about Bush personally. "He thought Bush was a lightweight but a nice enough guy," says a close McCain associate. That ended in South Carolina. During a commercial break in a debate there, Bush put his hand on McCain's arm and swore he had nothing to do with the slander being thrown at his opponent. "Don't give me that shit," McCain growled. "And take your hands off me."

McCain lost South Carolina and, eventually, the nomination. He endorsed his opponent--but mocked the ritual, robotically telling reporters, "I endorse George Bush, I endorse George Bush, I endorse George Bush." And months would pass before he would campaign for him against Al Gore. "The tension was palpable," recalls Scott McClellan, the Bush aide who went on to become White House press secretary. "The two were cordial, but McCain would get that forced smile on his face whenever they were together."

A Maverick in Full

The U.S. Senate was split down the middle between Democrats and Republicans when Bush took office in January 2001. The Democratic leader, Tom Daschle, knew that all he needed to take control of the chamber was the defection of one Republican. Daschle had three targets, all of whom were finding themselves increasingly alienated from and isolated within the GOP: Jim Jeffords of Vermont, Lincoln Chafee of Rhode Island and John McCain of Arizona.

Jeffords and Chafee were members of a dying breed--the liberal New England Republican. McCain, on the other hand, was a Western conservative from Arizona who had gone to Congress as a Reagan Republican. But after the searing experience of getting entangled in the Keating Five scandal in the 1980s, McCain had grown increasingly independent, pursuing campaign-finance reform and other causes that made his fellow Republicans doubt his ideological convictions.

But it was his bid for the White House in 2000 that broadened McCain's appeal--and opened his eyes to his own potential clout. He ran as the candidate of reform--the anti-Establishment maverick--and while he lost, in the process he became the most popular politician in America. "That campaign changed him," says John Weaver, who was McCain's chief political adviser for a decade, until last summer when he left in a staff shake-up. "He became a rock star. On the trail he discovered all these new issues. How could he go back to the Senate and not talk about the need for a patients' bill of rights or stand up and say Bush's tax cuts were unfair?"