Twain called the Conklin's self-filling pen, which he endorsed in advertisements beginning in 1903, a "profanity saver" because it wouldn't roll off his desk.

In the New York Public-School system, we read Huck Finn in the eighth grade. For a kid from the suburbs, the picaresque story of Huck and Jim was wonderfully exotic. Who wouldn't want to live along the Mississippi and drift down the river on a skiff? The buddy story of Huck and Jim was not only a model of American adventure and literature but also of deep friendship and loyalty. It's not hard to see why Ernest Hemingway said all of American literature can be traced back to Mark Twain. Plus, Twain was funny, the hardest trick of all.

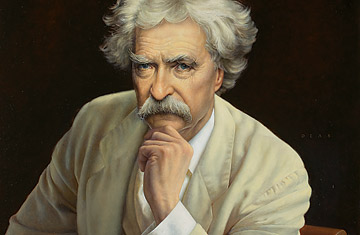

Mark Twain is the subject of our seventh annual Making of America issue.

We chose him--after a succession of Presidents: Jefferson, Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt and Kennedy, as well as explorers Lewis and Clark and inventor Ben Franklin--because he represents a vital tradition in American politics and culture: the comedic commentator on serious matters, the funnyman as our collective conscience who can utter uncomfortable truths that more solemn critics evade. In an election year when so many Americans are getting their news from nontraditional sources, Twain is the godfather of Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert as well as the comic voices who influenced them, from Lenny Bruce to Richard Pryor to Kurt Vonnegut. And Twain, with Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, created the literary dna that helped shape race relations in America over the past century.

We asked Roy Blount Jr., a literary humorist in the Twain tradition, to put the author in perspective. In his essay, Roy plumbs Twain's deeply contrarian nature and his abiding sadness and even bitterness at what he saw as collective human folly. For Twain's influence on race relations, we asked novelist and scholar Stephen L. Carter to address Twain's views on slavery and African Americans. There have been few books more controversial in U.S. history than Huck Finn, but Carter concludes that the novel is profoundly antislavery and that Twain pioneered the sophisticated literary attack on racism. The cover package is introduced and edited by our own Richard Lacayo, who also produced our Teddy Roosevelt issue.

For the fifth time, portrait artist Michael J. Deas has created our cover. He does painstaking research into his subjects and takes about 12 weeks to finish a painting. At left, you see the full portrait (on the cover, we crop the image much closer), which shows Deas' obsession with detail, down to one of the fountain pens Twain favored. The pen, made by Conklin Pen Co., originally of Toledo, Ohio, had a ridge on it that prevented the pen from moving. "I prefer it," said Twain in a 1903 endorsement, "because it is a profanity saver; for it cannot roll off the desk." The pen is still being made today. And like the pen he used, Twain is still in fine form, bold and clear and penetrating.

Richard Stengel, MANAGING EDITOR