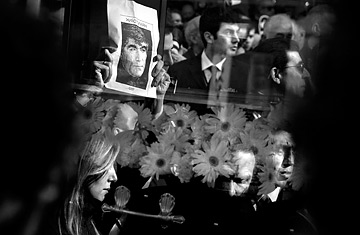

A funeral procession for Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink. Dink was shot in broad daylight outside of his newspaper's office in Istanbul.

Ninety-two years ago, the "young Turk" regime ordered the executions of Armenian civic leaders and intellectuals, and Turkish soldiers and militia forced the Armenian population to march into the desert, where more than a million died by bayonet or starvation. That horror helped galvanize Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jew, to invent the word genocide, which was defined not as the extermination of an entire group but rather as a systematic effort to destroy a group. Lemkin wanted the term--and the international legal convention that grew out of it--to encompass ethnic cleansing and the murdering of a substantial part of a group. Otherwise, he feared, the world would wait until an entire group had been wiped out before taking any action.

But this month in Washington these historical truths--about events carried out on another continent, in another century--are igniting controversy among politicians as if the harms were unsubstantiated, local and recent. At stake, of course, is the question of whether the U.S. House of Representatives should offend Turkey by passing a resolution condemning the "Armenian genocide" of 1915.

All actors in the debate are playing the roles they have played for decades. Turkish General Yasar Buyukanit warned that if the House proceeds with a vote, "our military ties with the U.S. will never be the same again." Having recognized the genocide while campaigning for the White House, President George W. Bush nevertheless followed in the footsteps of his Oval Office predecessors, bemoaning the euphemistic "tragic suffering" of Armenians and wheeling out men and women of diplomatic and military rank to argue that the resolution would harm the indispensable U.S.-Turkish relationship. In Congress, Representatives in districts populated by Armenians generally support the measure, while those well cudgeled or coddled by the President or Pentagon don't. Official pressure has led many sponsors of the resolution to withdraw their support.

One feature of the decades-old script is new: the Turkish threats have greater credibility today than in the past. Mainly this is because the U.S. war in Iraq has dramatically increased Turkish leverage over Washington. Some 70% of U.S. air cargo en route to Iraq passes through Turkey, as does about one-third of the fuel used by the U.S. military there. While Turkey may react negatively in the short term, recognition of the genocide is warranted for four reasons. First, the House resolution tells the truth, and the U.S. would be the 24th country to officially acknowledge it. In arguing against the resolution, Bush hasn't dared dispute the facts. An Administration that has shown little regard for the truth is openly urging Congress to join it in avoiding honesty. It is inconceivable that even back in the days when the U.S. prized West Germany as a bulwark against the Soviet Union, Washington would have refrained from condemning the Holocaust at Germany's behest.

Second, the passage of time is only going to increase the size of the thorn in the side of what is indeed a valuable relationship with Turkey. Many a U.S. official (and even the occasional senior Turkish official) admits in private to wishing the U.S. had recognized the genocide years ago. Armenian survivors are passing away, but their descendants have vowed to continue the struggle. The vehemence of the Armenian diaspora is increasing, not diminishing. Third, America's leverage over Turkey is far greater than Turkey's over the U.S. The U.S. brought Turkey into nato, built up its military and backed its membership in the European Union. Washington granted most-favored-nation trading status to Turkey, resulting in some $7 billion in annual trade between the two countries and $2 billion in U.S. investments there. Only Israel and Egypt outrank Turkey as recipients of U.S. foreign assistance. And fourth, for all the help Turkey has given the U.S. concerning Iraq, Ankara turned down Washington's request to use Turkish bases to launch the Iraq invasion, and it ignored Washington's protests by massing 60,000 troops at the Iraq border this month as a prelude to a widely expected attack in Iraqi Kurdistan. In other words, while Turkey may invoke the genocide resolution as grounds for ignoring U.S. wishes, it has a longer history of snubbing Washington when it wants to.

Back in 1915, when Henry Morgenthau, the U.S. ambassador to Turkey, protested the atrocities to the Turkish Minister of the Interior, the Turk was puzzled. "Why are you so interested in the Armenians anyway?" Mehmed Talaat asked. "We treat the Americans all right." While it is essential to ensure that Turkey continues to "treat the Americans all right," a stable, fruitful, 21st century relationship cannot be built on a lie.