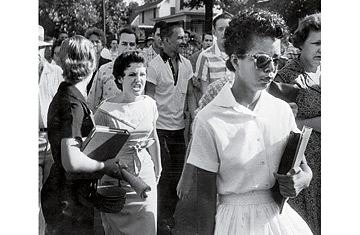

Elizabeth Eckford ignoring the insults of Hazel Bryan (2nd from the L), one in the crowd of jeering whites hard on her heels as she heads to Little Rock Central High School where Natl. Guardsmen prevented her entry as 1 of 9 black students trying to attend all-white school.

The 50th anniversary of the Little Rock school crisis is a powerful lesson in the complicated calculus of social change. People on all sides of the civil rights issues in 1957 were shocked by the sight of white mobs and the Arkansas National Guard, under orders from Governor Orval Faubus, blocking nine black children from entering the city's Central High School. When President Dwight Eisenhower sent in the 101st Airborne to protect the students, some feared this and other efforts to desegregate the nation's schools might signal the start of a second civil war. But the Governor backed down, and on Sept. 25 the nine became the first blacks to enroll at the high school.

Earlier this year the U.S. Mint issued a silver dollar commemorating the event, and throughout the anniversary's week there will be other observations marking this turning point in U.S. history. But the joy will be somewhat muted, for American schools are still nearly as segregated as they were 50 years ago. Almost three-quarters of African-American students are currently in schools that are more than 50% black and Latino, while the average white student goes to a school that is 80% white, according to a 2001 study by the National Center for Education Statistics. Similarly, a 2003 study by the Civil Rights Project at Harvard found that 27 of the nation's largest urban school districts are "overwhelmingly" black and Latino, and segregated. The percentage of white students going to school with black students is "lower in 2000 than it was in 1970 before busing for racial balance began," the report said.

And public education in the U.S. is not only separate, it is often unequal. In 2005 the New York Times reported that the average black or Latino student graduating from high school "can read and do arithmetic only as well as the average eighth-grade white student." At the same time, on average, white elementary-school-age children go to schools in which about a third of the students qualify for free or low-cost lunches, while the typical black or Latino grade-schooler attends one in which two-thirds of children are in the reduced-price lunch program.

The clear evil of racism explained the gaps in opportunities and achievement between black and white children back in 1957. But that kind of open malice is harder to find today, and the reasons for current discrepancies are more complicated and more challenging. At the time of Little Rock, no one could foresee that Hispanics would become the nation's largest minority and perhaps its most segregated group, but both are true today. It is also true that white flight and now the exodus of middle-class black families fleeing to the suburbs to escape crime have continued to take good students and active parents away from city schools. But an even larger factor in early 21st century America is the declining number of school-age white children and increasing number of school-age minorities. Such demographic shifts are making it even more difficult to integrate American schools by race or class.

These realities have become an issue in recent court decisions. Judges point to high levels of residential segregation as the root cause of school segregation and question the wisdom of using children and schools to remedy adults' preferences for isolating themselves by income and race. This year the Supreme Court ruled that voluntary school-integration plans in Seattle and Louisville, Ky., violated the rights of students to be judged on individual merit even if the ruling means that many schools remain segregated by race and class. It was a sad decision, acknowledging the defeat of the ideals and aspirations of Little Rock and the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision that made segregation illegal. But it should also be hailed for acknowledging new realities: first, even as we celebrate what happened 50 years ago in the glory days of the civil rights movement, the political will to integrate schools in this country is long gone. So, too, is the desire to fix every economic inequity before delivering quality education to all children.

But there is hope. Fifty years after critics charged one Republican President with risking a civil war by sending federal troops into a Southern city to enforce integration, a Republican President is taking on the problem of underperforming big-city schools and what he calls the "bigotry of low expectations." President George W. Bush is seeking renewal of the No Child Left Behind law, which holds schools accountable for teaching every student and narrowing the achievement gap regardless of a child's color, income or family background. Despite its shortcomings, like training students how to pass standardized tests instead of instructing them how to think critically, the President's plan is worthy simply for insisting that all children can learn. Fifty years after U.S. troops had to escort nine black children to school in Little Rock, the issue is still how to take race out of the equation when it comes to educating every American child.

Williams is a senior correspondent for NPR, an analyst for Fox News and the author of Enough