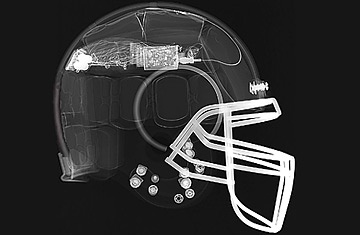

X-ray of football helmet.

Coming soon to a worried parent near you: a sales pitch for a $1,000 football helmet that can monitor the precise location and severity of impacts to little Johnny's head. Leading helmetmaker Riddell plans to begin flooding high schools with take-home brochures this month and to start shipping this concussion-sensing gear to families in November. Says Riddell marketing chief Jim Heidenreich: "If people buy $1,000 drivers and $500 baseball bats, we hope they'll spend that kind of money on head protection."

The football field, to borrow a phrase from sports-injury researchers, is an impact-rich environment. Players frequently knock heads, but it's hard to predict which of the many hits will result in brain-rattling concussions, which are relatively few in number and--contrary to popular belief--often occur without loss of consciousness. Eight colleges, including three Big Ten schools, are using the team version of Riddell's high-tech helmets, which wirelessly relay real-time data--gleaned from the same sensors found in car air bags--to a sideline computer that can send a pager alert if a player receives a hit or a series of hits that exceed a certain magnitude. The new system for individual consumers works in much the same way except that the helmet uploads impact data onto a PC after a practice or game and a player's family can log in for a Web-based analysis that may suggest seeking medical attention.

Use of these helmets may seem like a no-brainer. But there's one big problem besides cost: every concussion is different. One player may emerge unscathed from a massive hit, while his teammate starts seeing stars after getting clocked with half as much force. So it's unclear what coaches and parents can do with the impact data, at least until more is known about what causes concussions. "We don't pull people out of a game or a practice simply because they registered some high-value hit," says Kevin Guskiewicz, director of the University of North Carolina's Sports Medicine Research Laboratory, who will soon publish five semesters' worth of helmet data from UNC players showing the wide range of force that led to concussions.

To help pinpoint which impacts affect brain function and how, Brown, Dartmouth and Virginia Tech are starting a five-year study using the sensor-laden helmets that is funded by the National Institutes of Health. The study's principal investigator, Richard Greenwald, co-invented the monitoring technology, and his company, Simbex, is already making inroads into other markets. It just completed an Army order for 20 combat helmets equipped with sensors to monitor bomb blasts and is working on a deal to sell ski helmets that can track the head banging that snowboarders often endure on half-pipes and terrain fields. Greenwald's two young sons have been wearing prototypes on the slopes as well as data-streaming wrist guards Simbex is developing. Let the impact monitoring, er, games, begin.