Urban legend the Pull of Tangier

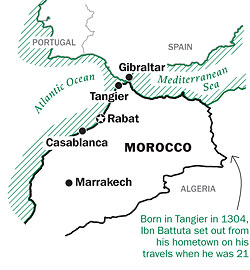

In 1977, when I was 9 years old, my parents took my siblings and me on a trip to Tangier in the north of Morocco. It was the middle of summer, and a fierce wind blew through the hilly streets of the city, bringing with it the smell of frying fish and cigarette smoke. In the medina, the city's old quarter, women in wide-brimmed straw hats, their hips girded in red-and-white-striped blankets, sold mint and turnip along the alleys. Boys sat behind open cartons filled with contraband from Spain — transistor radios, plastic watches, disposable razors — calling out prices not in dirhams, but rials, the older unit of currency. Outside their stores, middle-aged shopkeepers, the hoods of their djellabas pulled back behind their ears, spoke in dulcet voices, with long vowels and soft consonants. To a little girl from the capital, Rabat, these regional differences in dress, customs and dialect were proof that Tangier was different. Tangier was legendary. Tangier was mythical.

That year, in my picture encyclopedia, I had been reading about Greek myths — including that of Hercules, who was said to have rested near Tangier after finishing his 12 labors. So I was particularly excited when, the next day, we went to see the Caves of Hercules, 14 km outside the city. What awaited us inside was a breathtaking view: a gap in the wall in the shape of a reverse Africa and, silhouetted against it, the turquoise blue sky and the deeper blue of the Atlantic Ocean. While I held on to my father's hand, afraid I might fall into the water, a few teenage boys fearlessly jumped in the ocean. Whether the Caves of Hercules were a geological wonder or the result of the painstaking work of indigenous tribes, no one could really tell me. In Tangier, the line between myth and reality is a fine one.

Hercules wasn't the only traveler to have found haven in the city. The Romans arrived in the 1st century B.C.; then came the Vandals, Umayyads, Abbasids, Idrisids, Marinids and many other dynasties, Berber or Arab, Muslim or Christian, local or foreign. The Portuguese invaded in the 15th century, before they — as well as Tangier itself — fell to Spanish rule. The English turned up a few years later. They all wanted the same thing: a city whose strategic location at the tip of the continent would enable them to control much of the trade from the interior.

And they all left — although, like Hercules, they left behind something of themselves in Tangier. The Spanish have the Gran Teatro Cervantes, a 1,400-seat theater where their biggest musical and opera stars performed in the years between the two World Wars. The British have the Church of St. Andrew, built on land donated to their community by Sultan Hassan I, and whose bell tower is shaped like a minaret. Tangier has a way of seducing you, then rejecting you, only to invite you to return. Even after nearly 25 years away, its most famous native son, Ibn Battuta, went back, too.

And they all left — although, like Hercules, they left behind something of themselves in Tangier. The Spanish have the Gran Teatro Cervantes, a 1,400-seat theater where their biggest musical and opera stars performed in the years between the two World Wars. The British have the Church of St. Andrew, built on land donated to their community by Sultan Hassan I, and whose bell tower is shaped like a minaret. Tangier has a way of seducing you, then rejecting you, only to invite you to return. Even after nearly 25 years away, its most famous native son, Ibn Battuta, went back, too.

So did I — again and again. I was in Tangier most recently two years ago, this time with my husband. At first sight, the city seemed to me exactly the way I had left it: the medina's alleyways slowly filling up with people returning from afternoon prayers; the café where a man sat quietly smoking his sebsi, the local hash pipe. Yet many of the medina's oldest homes had been turned into bed-and-breakfasts, renovated in styles reflecting the idiosyncratic tastes of their European owners. The Café Central, where William Burroughs was said to have smoked his kef and which had the reputation of being seedy, looked downright respectable; men and women sipped lemonade on its terrace.

Leaving the medina, I walked across the Gran Socco to the Cinéma Rif, a cultural center run by the Moroccan visual artist Yto Barrada. I ordered some mint tea and sat down to drink it. Staring at me from a colorful poster on the wall was a smiling Jack Palance in Flight to Tangier. His goal, in all its Technicolor glory, was to recover a lost treasure. Perhaps, I thought, that is why so many keep coming back: they have left something of themselves in Tangier.

Lalami, a Moroccan novelist living in Los Angeles, is the author of Secret Son