Winning Essay: I Have a Dollar. My Neighbor Has a Million.

The Case of the Old Lady

The old lady walks in with the evening crowd, clutching an old bag that she sets down in the middle of the square. Surrounded by fancy windows promoting sparkling jewelry and diamond brocaded watches, and restaurants that charge more per meal than she spends on her food in a week, she unties her sac of wares and lays them out. Five minutes later, she is sitting on her foldable chair with her arms stretched out in front of her, with two packets of paper tissues at the end of each, quietly beckoning the flowing multitude around her to equip themselves for an unexpected case of a sweaty brow or a running nose.

It is Friday evening in Orchard, Singapore's premier shopping district, and the setting sun is making way for the revelry of yet another weekend. The old lady is beginning her lonely struggle to earn what she will need to feed herself tomorrow. She does not have a pension fund, social security, unemployment insurance or old-age benefits. Fluctuations in her daily earnings matter more to her than the ups and downs of the stock market, and she is probably as disconnected a participant as one can be in the economic juggernaut that Singapore is often spoken of as.

Yet if you could zoom out of this tiny island to gaze across the entire expanse of Asia, you will see that she is not alone. From homeless have-nots huddled together in the cold subways of Seoul, watching the smartly dressed haves hustle from swanky offices to heated homes, to a family of six sheltered in their one room wooden shack, listening to the thundering roar of airplanes landing on the strip beside the world's largest slum in Mumbai — jarring illustrations of social and economic inequality abound across this continent.

In the aftermath of the worst global financial crisis since the Great Depression, pundits in the hallowed financial centers of London and New York speak of Asia as the next success story. "Asian countries have been leading a recovery in the world economy," claims an IMF report. (1) Separately, Mr. Dominique Strauss-Kahn, managing director of the IMF, has remarked that "rapid economic growth has turned the region into a global economic powerhouse ... Asia's economic weight is on track to grow even larger." (2)

That most emerging economies from the Middle East to the Far East will continue to develop in the coming decades seems to be an inescapable conclusion. What is not guaranteed however is whether the fruits of this almost incontrovertible development will be available to all who dwell in these countries. As Asia has grown, so has an underbelly of penniless paupers. The bulk of Asian countries face a growing impoverished population that does not have any stake in the spoils being flaunted by their rich.

Which brings me to the question of this essay. If there is one challenge above all others that policymakers in the region need to address within the next decade, it is this: rising economic inequality. The only way for countries to ensure that their economic growth is sustainable and remains so through their own future and that of their children is to offer Inclusive Development to their citizens.

Economic Inequality

A new measure of global poverty — the Multidimensional Poverty Index — recently made headlines when it pronounced that "eight Indian states account for more poor people than in the 26 poorest African countries combined." (3) Quite a surprise given the contrast between the images that underprivileged Africa usually conjures — that of parched landscapes and malnourished children — and the beaming headlines Indian businesses generate in the pages of the world's business and financial dailies.

But the least confounded were those living in India itself. There, poverty moves alongside opulence like chocolate in a marble cake. BMWs and Mercedes run over fly-overs that shelter shanty towns and slums. And beggars beseech the drivers and the driven when the same cars stop at the next traffic light. The top 10% of India's population possesses 31.1% of the country's income, but the lowest 10% has access to only 3.6%. (4)

The numbers don't get much better if look across the northern border to the country's larger neighbor. According to a Credit-Suisse sponsored report released earlier this year, the average per-capita income for the richest 10% in China is 65 times higher (thrice as compared to even the official estimate) than the bottom 10%. (5)

|

A 2007 report by the Asian Development Bank identifies a litany of problems — economic, political and social, associated with rising inequality. (6) According to the report, in imperfect financial markets — a category even the most open of Asian economies belong to — inequality can trap the poor in an inescapable spiral, shutting them out from access to credit, education or business opportunities. To add to this, rising inequality increases pressure to redistribute income, adding potentially distorting mechanisms and making the markets even less perfect. The report declares that in the long run, "a high level of inequality may actually hinder... growth and development prospects."

Of a more immediate worry however, is the report's conclusion that rising inequality can impose tremendous social costs, "ranging from peaceful but prolonged street demonstrations all the way to violent civil war." So even as an economy develops, if it is unable to offer a stake in this development to its poorest, it is only creating a recipe for more social tension. The report quotes a study that "suggests that a 10 percentage point increase in poverty is associated with 23 – 25 additional conflict-related deaths."

A separate study released last year drew a positive correlation between higher socioeconomic inequality and negative social phenomena such as "shorter life expectancy, higher disease rates, homicide, infant mortality, obesity, teenage pregnancies, emotional depression and prison population." (7) And if recent events are anything to go by, there is clear evidence that such phenomena related to economic inequality are increasingly their toll across the region.

Some commentators have linked the attacks on schoolchildren in China to the rising discontent among its poor and marginalized, "many of whom feel left behind as the rest of China gets wealthier." (8) Similar explanations have been offered for the groundswell of support behind the violence in Thailand earlier this year. According to the country's own Ministry of Social Development, the public protests in the nation's capital offered an opportunity to the country's most strapped citizens "to vent their frustrations over declining living standards and the deepening divide between rich and poor." (9)

Biggest Challenge

In breaking down the effects of rising economic inequality, I am perhaps missing out on a slew of others. Nevertheless, it is not the mere number of such repercussions that makes it the most significant challenge facing Asia today. It is the fact that very high (and rising) levels of inequality can make other problems worse.

To present a few examples, inequality makes it more difficult to address problems of ethnic or religious tensions (socioeconomic disparity has been credited for adding fuel to fire in the troubled southern Thailand), or uncontrollable population (rising poverty means more people without access to family planning) or even natural calamities (the greater the number of impoverished, the more the potential victims without the means to prepare for or rescue themselves from floods and earthquakes).

|

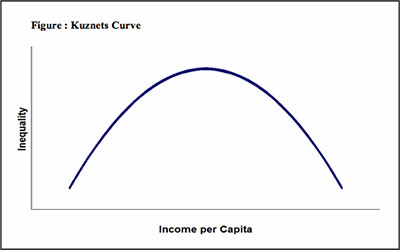

This theory is supported by data from the United States, where the share of wealth held by the top 1% of the society grew from 15% in 1775 to 45% in 1935, before falling back through the 1970's. (10) It could be that Deng Xiaoping had his one eye on these numbers when the then Communist Party leader launched market reforms in China in the 1970's with the famous words "Let some get rich first," (8) conceivably with the unspoken assumption that the rest will follow later.

What worked for America cannot however be expected work in Asia as well. This region is different; many developing countries here are more densely populated, which means that there are more poor who can band together in groups of sizeable clout, or be brought together by political parties with populist agendas, to demand for immediate action. In addition, the times have changed. With technology now connecting previously far-flung regions of a country, the underprivileged can now more easily gape at the affluence of their fellow countrymen, potentially inflaming their grievances even further.

Misguided Solutions

Waiting patiently therefore, for things to take their natural course as predicted by debatable economic theory, is not an option. Before discussing whether an alternative, affirmative approach can make a difference however, it will be helpful to take a detour and briefly look at the underlying causes of economic inequality. Figure Source: See 18

The ADB report quoted earlier claims that worsening inequality limits the poverty alleviating impact of economic growth. "Poverty rates would have been lower had the economies in question been able to achieve the growth in mean per capita expenditure that they did but with their previous and more equal distributions."

Which brings me to the proverbial million dollar question — Is it even possible for these two to go hand in hand? Is economic growth that is driven by free markets and loose regulation, as is the one that has been embraced by many Asian countries over the last two decades, compatible with an egalitarian society? Or is such a growth the very agent that kindles inequality in the first place?

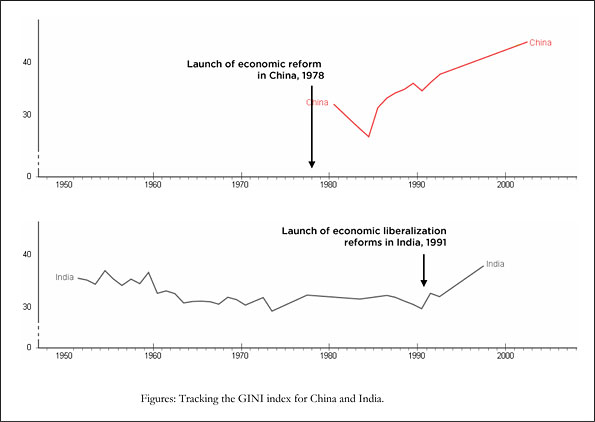

A cursory analysis seems to support the latter proposition. A capitalist economy rewards — with income

being the reward — initiative, skill, education, labor and capital. The fewer of these you possess, the less

is the eventual reward you walk away with. Empirical data further reinforces this sometimes anecdotally

perceived causality. As shown in the charts below, income inequality started rising after a brief drop a

few years into the launch of the Chinese economic reform in the late 1970's and hasn't looked back

since. Likewise, inequality in India also began its consistently upward climb only after the liberalization

reforms were launched in 1991.

It is not my intention however to prosecute economic liberalism for the ills of inequality. To do so would be to close one's eyes to the body of evidence that indicates otherwise. A comprehensive study published in 2007 by the Economic Freedom Network testified that there is nothing inherent in the idea of a free economy that worsens the state of its poor. (11) On the contrary, the authors of the report found that the freer a country is economically, the higher the income of its poorest, together with a better average income, life expectancy, and environment.

The real agents of inequality lie not in free-market driven growth itself, but one level below, in how this growth has traditionally been unevenly distributed across geographical regions (urban vs. rural) and industry sectors (non-agricultural vs. agricultural). (6)

And herein lies the understanding that guides us to the answer to Asia's biggest challenge today. Income redistribution or social redress measures as solutions are incomplete, ineffective or worse because they often follow from a case of mistaken provenance of economic inequality. Numbers that demonstrate a worsening inequality aren't so much a disease that needs a cure, but more a symptom indicative of the real malaise — that unevenly distributed economic growth offers uneven opportunities across peoples, translating into unevenly distributed income and hence economic inequality.

In the long run, it is opportunity and not income that we should strive to equalize. It will not eradicate inequality. But it will be an important step towards preventing it from growing further without compromising on continued economic growth.

The 'ESLH Framework

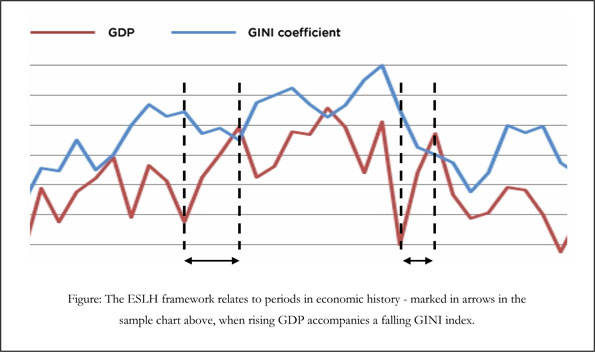

What remains then is for us to translate this idea of equality of opportunity into a set of policy guidelines. A detailed prescription of such recommendations is out of scope for this essay. Instead, what I would like to do is to outline a framework (let's call it the Economic Sustainability Lessons from History, or ESLH, framework) that can allow us to use empirical macroeconomic data from global economic history to pick out these guidelines ourselves.

Keeping in mind that any recipe for more equality that compromises on economic growth is unlikely to

be palatable to policy makers, investors or economists, the underlying idea of the ESLH Framework is to

hunt for instances in the history of developing nations where income inequality has fallen even as the

economy has continued to grow. Once identified, these windows of economic history can then be

studied further for specific policies that were designed to equalize opportunities and correspondingly

succeeded in equalizing incomes, while maintaining economic growth.

To see this framework in action, we can look at the example of Mexico. Between 1999 and 2008, Mexico's GINI coefficient fell 7 percentage points from 53 to 46, less than any recorded score for the country in the last 60 years. (15) In the same period, the country's real GDP continued to grow at an average rate of around 3%. (16)

What counsel can we draw from this experience? No doubt, the economies of Latin America and Asia are different, and there are things that worked in Mexico's favor that aren't applicable to Asia. But surely there should be a few ingredients of Mexico's success that can offer Asia a lesson in balancing economic growth with equality of opportunity.

There is at least one: the country's focus on rural development. A depreciation in rural poverty contributed significantly to Mexico's economic growth as well as its tempering inequality over the last decade. "Between 2000 and 2004, extreme poverty fell almost 7 percentage points, which can be explained by development in rural areas, where extreme poverty fell from 42.4 percent to 27.9 percent." 12

According to the World Bank, the factors that contributed to this reduction include "macroeconomic stability ... and the diversification of income from non-agricultural activities, such as tourism and services," arguably also applicable in equal measure in at least some parts of emerging Asia.

Gandhi said that India lives in her villages. Sixty-three years after the country's independence, his words are still true. Seventy-two percent of the country's one-billion-plus population today lives in rural areas. The same number for Nepal is 85%, Sri Lanka is 79%, Bangladesh is 76% and Pakistan is 66%. (13) For much of their history, these regions have formed the bread baskets for the rest of their countries. But with the rapidly declining share of agriculture in the GDPs for many of these countries, (14) it is imperative that there now be new avenues for development of rural territories, such as tourism as in the Mexican example above.

Bringing growth to the country-side, instead of luring village folk the other way with the glitter of swanky metropolitan development offers many advantages. It opens up new opportunities for the inhabitants of those areas without requiring them to desert their families or familiar landscapes. It reduces migratory pressures on urban centres, many of which in Asia are reeling from the effects of an exploding population density and an overburdened infrastructure. And it attracts more investment to the rural areas, allowing for economic growth to continue and at the same time be spread more evenly across communities.

Eliciting from the Mexican experience then, we have at least one strategic guideline that Asian leaders can follow in pursuing the goal of Inclusive Development: emphasis on rural development. There is of course no reason to stop at one. Following the ESLH Framework can allow for other such lessons to be learnt from economic histories of other countries as well that may be applicable in this region.

Conclusion

In many circles in emerging Asia, the recent financial crisis is already being talked about as history. A history that will teach us some lessons, but will not repeat itself, not in the immediate future at least. The future is bright. In the relentless journey of the Asia's economic bandwagon however, a growing number of its poor are being thrown off the cart along the way. Rising economic inequality now plagues countries across the continent's expanse, and threatens to undermine the very purpose that the polity of the region swears by: economic growth for its people.

It is essential for the long-term sustainability of this growth that Asian countries pursue a model of Inclusive Development, that offers a stake in the fruits of this progress to their poorest. The ESLH framework outlined in this essay helps us discover periods in our economic history when economic growth did not come at the expense of rising economic inequality, and learn from them. Nevertheless, this framework is but one step towards formulating an effective response. The key point is this — unless we are able to ensure that economic development creates new opportunities for each and every one amongst us, we may just be laying the stage for more men and women to give up hopes for a better future and resort to the business of selling paper tissues on street sidewalks.

Bibiliography

1. US economy back on track; IMF raises Asia forecast. Dated: October 29 2009.

2. "Analysis: IMF challenges Asia to change its economic habits." Dated: July 19 2010.

3. "'More poor' in India than Africa." Dated: July 13, 2010.

4. CIA - The World Factbook. South Asia - India. 5. "Study estimates China's rich hiding $1.4 trillion." Dated: August 13, 2010.

6. "Inequality in Asia, Key Indicators 2007, Highlights". Report by Asian Development Bank.

7. This claim is taken from the Wikipedia page for "Economic Inequality", which labels it as having been referenced from Wilkinson, Richard; Pickett, Kate (2009). The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. Allen Lane. pp. 352. ISBN 1846140396.

8. "Some Got Rich First — and Richer Later." Dated: May 2010.

9. "UN report reveals deep social divide in Thailand." Dated: June 23 2010.

10. This data was taken from the Wikipedia entry for "Kuznets curve", where it is marked as having been referenced from "the sources presented by Alice Hansen Jones (1775); Edward Wolff (1915-1995)."

11. Chapter 1: "Economic Freedom of the World," 2007. Economic Freedom of the World: 2009 Annual Report.

12. "Mexico: Income Generation and Social Protection for the Poor." Dated: August 24 2005.

13. People Statistics > Percentage living in rural areas. (most recent) by country.

14. "Rapid growth of selected Asian economies. Lessons and implications for agriculture and food security: Synthesis report." FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Dated: April 2006.

15. This data was taken from the chart "Gini Index - Income Disparity since World War II" on the Wikipedia entry for "Gini coefficient". The chart is an original work authored by user Cflm001 "from publicly available data from the World Bank, Nationmaster, and the US Census Bureau."

16. This data was taken from the chart "Average annual GDP growth by period" on the Wikipedia entry for "Economy of Mexico", where it is marked as having been collected from a set of 3 sources: i. Crandall, R (September 30, 2004). "Mexico's Domestic Economy". in Crandall, R; Paz, G; Roett, R. Mexico's Democracy at Work: Political and Economic Dynamics. Lynne Reiner Publishers. ISBN 10-1588263002; ii. Cruz Vasconcelos, Gerardo. "Desempeño Histórico 1914 – 2004" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-17; and iii. "IMF World Economic Outlook Database, April 2010". Retrieved 2010-07-24.

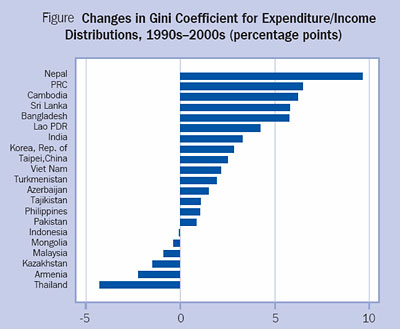

17. This chart is taken from page 6 (10 of 24 pages in PDF file) of 6.

18. This figure is taken from the Wikipedia entry for "Kuznets curve", where it is marked as being a "Hypothetical Kuznets curve. Empirically observed curves aren't smooth or symmetrical." The caption of the figure also includes a reference to the article "The Richer-Is-Greener Curve" for examples of "real" curves.

19. As in 15, these figures were referenced from the chart "Gini Index - Income Disparity since World War II" on the Wikipedia entry for "Gini coefficient." The chart is an original work authored by user Cflm001 "from publicly available data from the World Bank, Nationmaster, and the US Census Bureau."