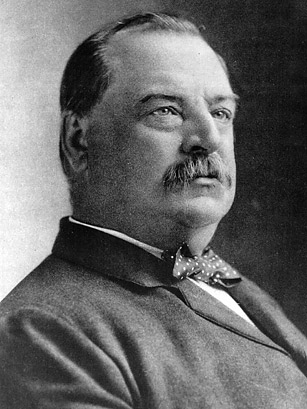

Although President Grover Cleveland signed the 1894 law that made Labor Day a federal holiday, he did so with political motives in mind. Just months before the holiday was made official, Cleveland had ordered federal troops to Chicago to quell a strike by the American Railway Union at the Pullman Palace Car Company. While workers fought against executives who had cut their wages by 25%, the President was concerned only with the fact that the strike had spread to other states, disrupting mail service and interstate commerce. The government force ended the strike within a week, but at least a dozen people were killed in the process. Cleveland, mindful of his future re-election campaign, made appeasement a top priority, so labor legislation was rushed through Congress and the bill passed just six days after the strike's end.