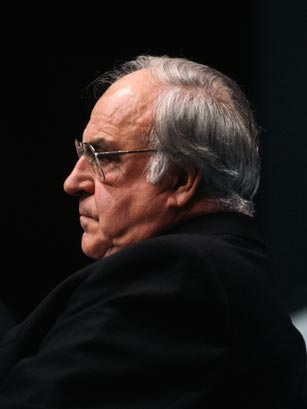

Helmut Kohl, Chancellor of Germany and leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), during its congress for the reunification of the two states

Dreams, like revolutions, have the power to galvanize wildly disparate forces. The dream of a unified Germany, so long as it seemed unattainable, commanded the West's official support for decades. But when the Berlin Wall crashed down in November 1989, NATO's decades of pro forma unanimity also tumbled — into confusion, hesitancy and doubt. Of all the European leaders, one man read the moment and seized it. Helmut Kohl, the consistently underestimated master of German domestic politics, knew instinctively that the communist regime in East Berlin was kaput. He saw that unification of Germany and the mending of Europe were now within reach. He set to work, overcame every objection and obstacle, and in December's all-German election became, literally, the unification Chancellor.

At first his obstacles included not only anxieties in Britain, France and the Soviet Union but the mood in East Germany as well. The peaceful revolution had been led mostly by intellectuals, members of the clergy and students who believed their state should become democratic but remain socialist and separate from West Germany. As an initial response, Kohl proposed a federation of the two German states.

That was his only stab at a go-slow approach, and events quickly swept it aside. East Germans demonstrated their rejection of half measures by surging into West Germany: 340,000 in 1989 and more than 300,000 in 1990. Kohl headed the other way, wading into East German politics with a clear-cut promise: a vote for his Christian Democratic Union was a vote for unification. In March his conservative coalition won by a landslide in East Germany's first free elections.

While Kohl was still viewed by many as a provincial politician, he proved to be a diplomatic whiz. His biggest problem of all remained Moscow. The Soviets, who make a cult of memorializing World War II, resolutely opposed German unity. After a visit from Kohl in February, however, President Mikhail Gorbachev modified his position, conceding that unification was Germany's right, but not immediately and not inside the NATO alliance.

Unperturbed, Kohl flew back to the Soviet Union in mid-July and went hiking in the Caucasus with Gorbachev. The two leaders were downright jovial as they announced that the united Germany would enjoy full sovereignty, including the right to join NATO. Kohl had not depended entirely on persuasion to bring Gorbachev around; he also agreed to pay most of the tab for a package of joint projects.

Now that Kohl's triumph is complete and he has won a new four-year mandate as Chancellor of the united Germany, he still cannot sit back and enjoy it. Like most visionary projects, German unification will cost much more than the original estimates, requiring hundreds of billions of deutsche marks to modernize the five states newly added to Germany. This means increasing budget deficits and possibly new taxes.

Germany also feels it must support the economic and political development of Central and Eastern Europe, which remain perilously unstable. That task, far too big for Germany alone, will require a major effort from the whole European Community. By bringing Western Europe to the aid of the East, Kohl continues to help the Continent mend its divisions.