"Don't think men will fly for a thousand years," Wilbur Wright predicted in 1901, shortly after testing a glider that he and his brother had built. Well, Wright was wrong.

He and his brother Orville were the proprietors of a bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, but it was their interest in aviation rather than cycling that would grow into an obsession. As early as the mid-1890s they were reading everything they could about the prospects for flight.

They were diligent, smart students, not to mention talented engineers and mechanics. One day, observing buzzards in flight, the brothers agreed that the birds were changing the angle of their wings to balance in a shifting wind. It looked like a clue.

By 1899 the Wright brothers were putting their notion to work, building kites with movable wingtips. In their gliders, which they began building the following year, control wires were connected from the pilot's position out to the wings. In the summer of 1901, the Wrights put their glider through hundreds of trials over sand dunes near Kitty Hawk, N.C. The reason Wilbur spoke so pessimistically about the future of manned flight was that the glider could never be kept aloft longer than a few minutes per day — total.

According to one family member, Wilbur was ready to give up entirely. Orville, the optimist, urged his brother to stick with it. Back in the bike shop, the Wrights constructed wind tunnels and tested more than 200 different wing shapes. With a new wing and the addition of a rear rudder, their 1902 glider made a record 622.5-foot flight.

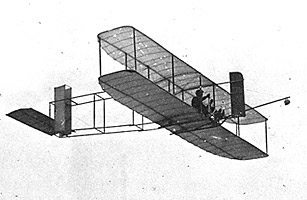

Now for a motor. In 1903 the brothers built what they called simply the Flyer. It was a 600-pound plane made of wood, muslin and wire. It sported two propellers and a four-cylinder engine. That September, Orville, 32, and Wilbur, 36, returned to Kill Devil Hills near Kitty Hawk, one of the windiest places in the country, lugging their craft 800 miles to its meeting with history.

The Wrights, adventurous men as well as inquisitive engineers, did their own flying. They were pioneers but not daredevils, careful not to put a thing aloft before they thought it truly ready. "I do not intend to take dangerous chances," Wilbur wrote to his father, "both because I have no wish to get hurt and because a fall would stop my experimenting, which I would not like at all." By December, the Wrights were confident they had a device that was ready to fly. Wilbur's attempt on the 14th failed, and on the 17th it was Orville's turn. He climbed into the wild-looking flying machine. Rube Goldberg wasn't drawing his contraptions yet, but had he been, his sketches might have looked like the Wrights'. Orville lay facedown, his hips resting on a wooden cradle. By shifting his hips from one side to the other, he could tug on wires connecting the cradle to both the wingtips and rudders.

After a preflight check, Orville released a wire that restrained the Flyer on its 60-foot wood-and-metal track. Wilbur gripped a wingtip to steady the machine as it accelerated. He ran alongside the airplane like a father guiding a son on a first bicycle attempt. The Flyer powered down the track, picking up speed and plowing into the gusty 27 mph headwind. At seven mph, it took off. The Flyer dipped, then rose to 12 feet, dipped again, rose again. It flew 50 feet ... 80 ... 120 feet!

And then, with "a sudden dart," it fell.

"They done it!" called out Johnny Moore, a local who witnessed the event. "Damned if they ain't flew!" The flight had lasted only 12 seconds and covered but 120 feet — less than the wingspan of a 747 — but the Wrights had, in fact, done it. They had lived one of mankind's longest-held dreams: They had flown. They had succeeded in taking a heavier-than-air machine into the skies in a self-propelled, sustained and controlled flight.

The Wright brothers completed three more flights that first day, the longest of them lasting 59 seconds and traveling 852 feet. Suddenly the future, which had looked so bleak and unpromising to Wilbur, was boundless.