October 5, Oslo, Norway

The Dalai Lama came out of his room with hands extended, as open and relaxed as if it were just another day. Twenty-four hours earlier, he had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace, while enjoying a meeting outside Los Angeles with scientists. I was intruding on him with questions for this magazine and entered a modest ranch-house where busy aides were dealing with congratulatory phone calls and faxes from around the globe. It was a moment of great hope and possibility for Tibet and its supporters, but the Dalai Lama was characteristically measured, as if this were just another step on a long path with no short-term guarantees.

The minute he saw me, in the bright October sunshine, he grabbed me by the hand — as he would have grabbed anyone — and whisked me off into a small room where we could talk. Our first few minutes in the room, he looked around for a chair in which I (not the new Nobel laureate) would be comfortable. Then he looked at me directly, and said, "How should I spend the money?" At the moment when less realistic friends were claiming that Tibet's struggle was won, he said, "I really wonder if my efforts are enough." According to his Buddhist teaching, almost no victory is permanent, nor any loss.

Though Tibet had been occupied by People's Liberation Army troops 30 years before — moving the Dalai Lama to flee into exile — the Tibetan struggle for freedom had suddenly gained momentum in the months leading up to 1989. When monks in Lhasa began crying out for independence in 1987 and were suppressed, often violently, by Chinese soldiers, the Dalai Lama set about outlining a new policy in which he no longer called for independence for Tibet from China, only meaningful autonomy. And even after Beijing responded to his suggestion with more violence — demonstrations in March 1989 left 250 unarmed Tibetans dead in Lhasa and the city under martial law — the Dalai Lama continued to speak calmly for interdependence, dialogue and peace. In rewarding him, the Nobel committee seemed to be sending a larger message to the world that velvet revolutions could achieve more than the Tiananmen protests ever did.

Yet, 20 years on, the Dalai Lama's circumspection on that sunny day looks like prescience, as Tibet is ever more in Beijing's grip, and 20 years closer to losing its distinctive identity. In Burma Aung San Suu Kyi, who was placed under house arrest that July (and rewarded with her own Nobel Prize two years later), is still in confinement, trying to outwit a brutal dictatorship. If 1989 means anything in Asia, it is that no hero of conscience can be sure of quick success.

But what the Tibetan leader — and others — were offering in that year sowed the seeds for a new sense of global responsibility. The first obligation of any Tibetan, the Dalai Lama was stressing with his new policy, was to work with China and look for common ground; in a planetary neighborhood, attacking what you see as your enemy is as senseless as punching yourself. And if China truly saw Tibet as part of itself, then it should try to help Tibet, with much-needed material and modern developments, without feeling the need to oppress it. The Nobel Committee effectively underlined this sense of interdependence by helping turn the Dalai Lama and his people from remote characters in a faraway kingdom to members of the global neighborhood.

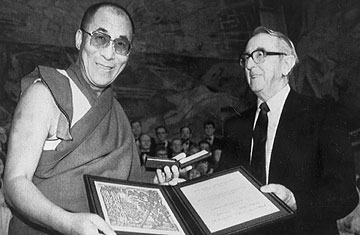

By the time the Dalai Lama went to Oslo to accept the award, "on behalf of the Tibetan people," near the end of the year, he had answered the question he posed to me. Some of the prize money went to Mother Teresa for her work with the poor. Some went to Africa, to help the hungry. And some went to Costa Rica, to help fund a university for peace. As 1990 began, it was hard for anyone to deny that the concerns of anywhere, in a global neighborhood, are the concerns of everywhere else.