As soon as the last chad was counted in Florida, Congress got to work on a new law that authorized $3.9 billion to buy new, high-tech voting equipment. On the whole, the new machines were an improvement over the old punch cards and levers, but many parts of the country now find themselves yearning for the old problems of paper.

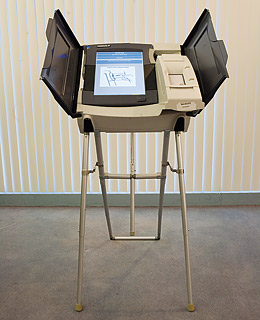

About one-third of voters this fall will use electronic machines, usually touchscreen systems that produce no paper record of the vote. If the machines are miscalibrated, they are known to malfunction, sometimes causing the selection of one candidate to show as a vote for another. But the bigger concern, which has been echoed by computer scientists, is that the machines have no independent paper backup. A memory failure or a corruption of the data leaves no route for a recount. The 2006 congressional election in Florida's 13th District produced the nightmare scenario. Republican Vern Buchanan won the contest by a margin of 369 votes. But in a single, Democratic-leaning county, more than 18,000 voters mysteriously failed to record a selection in the congressional race, an undervote as much as six times the rate of other counties. There is no way to know for sure what, if anything, went wrong.

Since that election, several states, including Florida and California, have required paper records for all electronic-voting devices. A bill in Congress that would mandate paper records of all machines nationwide has gathered 216 co-sponsors, including 20 Republicans.

Meanwhile, 11 million people live in counties that will use lever machines or punch-card ballots this year, even though the congressional deadline to replace that equipment passed in 2006.