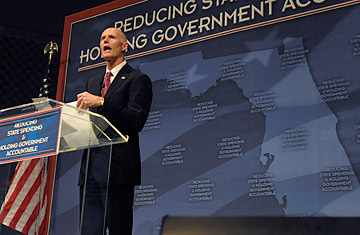

Florida Governor Rick Scott announces his new budget during a Tea Party event in Eustis, Fla., on Feb. 7, 2011

Florida Governor Rick Scott gives off a wide-eyed glow of certainty about everything he does. The Tea Party Republican has worn it from the moment he took office on Jan. 4, and since then he's rankled even conservatives in his own party with his imperious style. In his first eight weeks, he's put forth a budget proposal that slashes education spending — an area in which low-wage, low-tech Florida can't really afford to scrimp — by 15%; put the kibosh on a high-speed-rail project, funded with federal and private dollars, that could have created up to 30,000 jobs; campaigned to repeal a prescription-drug-monitoring law in a state where seven people die each day from an overdose; and pressed to kill two amendments that Floridians passed last November to curb the reckless gerrymandering of their legislative districts.

But as much as Scott would like to think he's revolutionizing government, it's best to remember that we already saw this movie not so long ago, starring former South Carolina Governor Mark Sanford — and the ending wasn't pretty. Long before "hiking the Appalachian Trail" became the media's favorite euphemism for Sanford's clandestine meetings with his Argentine mistress, the Palmetto State's chief executive was a conservative who, like Scott, was so convinced of his government-reduction dogma that he believed he could disregard his state legislature and the fellow Republicans who controlled it. And while he'll be remembered for the sex scandal, in many ways Sanford's lasting legacy will be the thwarted economic development of one of the nation's poorest states. He repeatedly vetoed trade centers and tourism-marketing initiatives, he left the public schools about as decrepit as he found them, and his miserly effort to lure a $500 million Airbus plant to South Carolina was widely blamed for the loss of that bid.

Like Sanford, the multimillionaire Scott is a fan of my-way-or-the-highway gestures. Florida's legislature, like most in the U.S., is hardly a heroic institution. But it was generally lauded in 2009 when, realizing Florida had become a national leader in prescription-drug abuse — overdose deaths from the painkiller oxycodone alone had more than doubled that year, to 1,185 — it voted to create a database to detect illicit prescriptions and crack down on "pill mills." The database was set to begin operation this year, and it looked all the more necessary in late February when the feds raided numerous clinics in South Florida and arrested 20 people, including five doctors.

But Scott has vowed to repeal the measure and has already eliminated the state's Office of Drug Control, which was supposed to help manage the database. One reason, he says, is that the database is too costly — even though its budget is just $1.2 million, and even that is being picked up by federal grants and private donations. Scott — who in 1997 resigned under a cloud as CEO of Columbia/HCA, the world's largest hospital corporation, when it was busted for massive Medicare fraud (although he wasn't charged personally) — calls the database an invasion of privacy, despite the fact that few such concerns have been raised in the 34 other states that have similar monitoring systems. "I'm extremely, extremely disappointed in the governor," GOP state senator Mike Fasano, who sponsored the legislation, said.

Fasano isn't the only Sunshine State Republican who is fuming. State-senate budget chairman J.D. Alexander told Scott that the governor violated Florida law recently when he sold two state airplanes and redirected the sale proceeds without consulting the legislature. Although Alexander had supported selling the aircraft, he scolded Scott in a letter for "not respecting the Legislature's constitutional duty." Scott says his counsel told him the unilateral move was legal, but Alexander appears to have the state constitution on his side.

But few actions have angered Florida pols in both parties more than Scott's February rejection of $2.4 billion in federal stimulus money for a $2.7 billion high-speed rail line between Tampa and Orlando. It would have been the first component in a proposed bullet-train system to alleviate traffic woes on Florida's long, car-clogged peninsula, not to mention a local incubator for the sorely needed high-tech enterprise. The GOP-led state legislature had spent the past two years laboring to win the federal funds, which the Obama Administration may now hand off to California. But Scott, who made clear his contempt for all things public sector during his campaign last year, called it a wasteful project that would end up putting "state taxpayers on the hook" despite the federal largesse. Two-thirds of Florida's 40 state senators rebuked him — most of them Republicans — including the senate majority leader.

Scott refused to budge, even when federal and Florida officials hammered out a revised plan of private-sector and local-government initiatives that guaranteed to keep the state off the hook. U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood gave the governor until the end of Friday, March 4, to change his mind; if he doesn't, some GOP state legislators say they're mulling whether to sue him for "exceeding his executive authority."

Scott's Sanfordesque disdain for the legislature also seems to extend to the electorate. In last November's midterm elections, more than 60% of the Sunshine State's voters approved two amendments requiring that their state and federal legislative districts be drawn on a nonpartisan basis. It was an especially important ballot measure, since Florida, the U.S.'s fourth most populous state, gained two congressional seats in the 2010 census (giving it 27), and many of those districts are absurdly contorted, having been designed to assure both parties virtually guaranteed seats.

Because any voting measure like that requires federal review, Scott's predecessor, former governor Charlie Crist, sent the antigerrymandering amendments to the Justice Department last year before leaving office. But Scott, with no explanation, almost immediately withdrew them from consideration when he took office. Even Fasano, who like many Republicans opposed the nonpartisan redistricting scheme, was disturbed by the high-handed move and has urged Scott to respect the majority in favor of the amendments — a majority that Scott, who was elected with only 48.9% of the vote, couldn't muster himself.

Still, perhaps it's not such a surprise that Scott dislikes the amendments. Their intent, after all, is to make elections more competitive by making politicians engage a more diverse cross-section of voters — and that agenda threatens the polarized, hyperpartisan environment that favors the likes of Scott. And Mark Sanford.