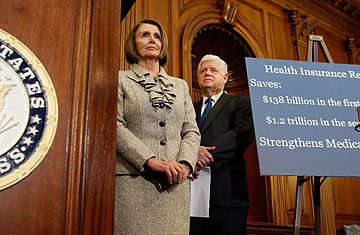

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D., Calif.) attends an event highlighting health care reform with Representative John Lawson (D., Conn.) at the U.S. Capitol March 18, 2010, in Washington, D.C.

It took a while, but on Thursday, House Democrats inched the health care boulder a bit further up the legislative hill after the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said the House's new health care proposal would slash $138 billion from the federal deficit by 2019, and extend health insurance to 32 million uninsured Americans. Earlier in the week, observers wondered why it was taking longer than expected for the key number cruncher to issue a verdict. Not only did the delay raise the question of whether all the compromises made to try to win broad enough support would make the bill too costly, but it also played into the hands of Republicans trying to keep the focus on the messy process of passing the bill rather than the substance in it.

Now that they have a CBO analysis which has made them "giddy," in the words of House majority whip Jim Clyburn, it clears the way for a vote as soon as Sunday afternoon on the Senate health-reform bill and a package of changes to the legislation assembled by House Democratic leaders. Indeed, the momentum seemed to be shifting as the day went on. In the wake of the positive CBO evaluation, Democratic Representatives Betsy Markey and Bart Gordon — who voted against an earlier House reform bill — committed to supporting the newly unveiled legislation. Also on board Thursday were members of the House Hispanic Caucus, who had threatened to withhold support for reform over provisions related to undocumented immigrants. While Democrats still do not yet have the 216 votes needed to pass the bill, an aide to the House Democratic leadership said House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is "feeling ultra-bullish." A source in the House leadership said Democrats are also getting a boost from grassroots reform supporters who stepped up pressure on wavering Democratic members through phone calls to their offices. And on the same day, President Obama postponed a trip to Asia — he was due to leave Sunday — a move that could embolden congressional Democrats eager to see the President is committed to pushing reform across the finish line.

In unveiling the CBO score, House Democrats also confirmed the changes they would make (which Obama had supported) to the underlying Senate bill, notably stripping out some sweetheart deals like a special Medicaid funding deal for Nebraska and a provision that would have given special treatment to Medicare Advantage recipients in Florida and a handful of other states. And the House package also makes some substantial changes to other policies in the Senate bill. Relative to the Senate bill, the House package would:

• Delay implementation of a tax on expensive health-insurance plans from 2013 to 2018. This cut 10-year revenue from the tax from $149 billion to just $32 billion. Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, which opposed the tax out of concerns it would end up hitting many union members' health plans, said in a conference call with reporters Thursday that he was satisfied with the change. While stressing that the Senate bill with the House package is "not a perfect bill," Trumka said it will "end a reign of insurance company terror" and is "an opportunity to change history we can't afford to miss."

• Close the Medicare Part D prescription drug gap known as the "donut hole," which leaves beneficiaries without prescription drug coverage once their costs exceed $2,830 (in 2010), and doesn't kick back in until they spend $4,550 out of pocket. This provision, which would cost the federal government about $20 billion over 10 years, gradually closes the gap beginning in 2011, so Medicare Part D recipients will eventually pay no more than 25% co-insurance for name-brand drugs. In 2010, Medicare Part D enrollees who reach the gap will receive $250 rebate checks.

• Delay excise taxes on various health industries, such as the pharmaceutical sector and health-insurance sector. These taxes will most certainly be passed directly onto consumers, so the later they are implemented, the later consumers will see drug prices and health-insurance premiums rise as a direct result.

• Make deeper cuts to the Medicare Advantage program, a federally funded program in which private insurers provide Medicare benefits to seniors. The government currently pays MA plans about 14% more than it pays for traditional Medicare.

• Temporarily increase payments to primary care providers who care for Medicaid payments. Democratic reform would add some 15 million people to the Medicaid rolls, and critics have said this will strain doctors already buckling under Medicaid reimbursement rates, which are substantially lower than what private insurance pays. In 2013 and 2014, this provision would pay primary care providers the same reimbursement rates as Medicare, which falls in between Medicaid payment rates and private insurance. The House package would also increase federal funding to states for Medicaid.

• Increase penalties for larger employers who do not offer health insurance and have at least one employee who qualifies for federal subsidies. Companies with more than 50 employees would have to pay an annual $2,000 penalty for each worker at the firm, even if only one qualified for subsidies. (Penalties assessed for the first 30 workers would be waived, however.)

• Makes subsidies to low- and middle-income Americans buying insurance through exchanges more generous, but calls for those subsidies to grow at a slower rate over time.

• Increases taxes on payroll and unearned income (such as capital gains, dividends, interest) for individuals earning more than $200,000 per year and married couples earning more than $250,000.

These changes essentially represent a compromise between the Senate and House bills. But for them to become law, the Senate would have to pass them separately after the House under a process known as reconciliation, which requires only a simple majority of 51 senators. Still, reconciliation can be procedurally arduous and Senate Republicans plan to use parliamentary rules to try to delay or stop the House package from being passed. Without this, the Senate bill itself — with its sweetheart deals and unadjusted tax on high-value insurance plans, for example — would stand as law.

To assuage House members' concerns that Senate Democrats could too easily give up the fight, leaders in the chamber are lobbying for one of two scenarios: for at least 50 Senate Democrats to sign a letter pledging to vote in support of the House package, or for 50 Democratic Senators to co-sponsor the House package.