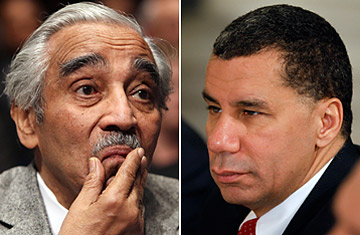

From left: Charles Rangel and New York Governor David Paterson

It's been a brutal week for Harlem politicians. On March 3, Charlie Rangel, the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee and 20-term representative from New York's 15th district, announced he would temporarily relinquish his stewardship of the powerful tax-writing body in the wake of an ethics investigation that found he violated protocol by accepting corporate-funded trips to the Caribbean. The decision came on the heels of scandal-scarred New York Governor David Paterson's announcement that he will not run for re-election in the fall. The synchronized setbacks of two longtime Harlem leaders have prompted a flurry of obituaries for the Harlem dynasty, which for decades has been the unquestioned nerve center of black politics in the U.S.

Rangel and Paterson's father Basil were members of Harlem's Gang of Four, along with Percy Sutton — a civil rights activist, lawyer and local power broker, who died Dec. 26 at 89 — and David Dinkins, who served as mayor of New York City from 1990 to 1993. The group inherited a tradition passed down from trailblazers like Adam Clayton Powell Jr., whom Rangel unseated in 1970, and together shattered scores of racial barriers, attaining offices once dismissed as off-limits and paving the way for the ascension of black leaders around the country. In the process, they turned Harlem — long the epicenter of African-African culture — into a political mecca, its pull strong enough to entice former President Bill Clinton to base his foundation headquarters on the district's main thoroughfare of 125th Street. But with Rangel, 79, giving up his gavel, the Paterson era in Albany lurching toward an end and Dinkins having long since stepped away from the scene, Harlem's political might has diminished.

The current crop of Harlem politicians know that measuring up to their predecessors' accomplishments is impossible. "They are absolutely historic figures," says New York state assemblyman Keith Wright, who represents the district. "Without Percy, Charlie, Basil and Dinkins, you probably wouldn't have this number of [politicians] in Brooklyn, in the Bronx, in Queens. They're pioneers." But Wright acknowledges that the power they accumulated is now flowing elsewhere — to the outer boroughs of New York City and to cities like Chicago, President Barack Obama's adopted hometown.

In part, the slippage is a function of the district's changing character. Though Harlem continues to be a capital of black culture, it is no longer predominantly black. Gentrification, a vaunted history and a prime location near Manhattan's Central Park have made it a magnet for New Yorkers of all stripes, and today less than half of the district's residents are African American. The demographic realignment means the district's elected officials face different political challenges. "When the baton is passed to you, you have to run the race of the moment," says Bill Perkins, a state senator who represents pockets of Harlem that are heavily African American, the Hispanic stronghold of East Harlem and parts of the affluent Upper West Side. Titans like Sutton and Rangel, he says, "were the trailblazers. They were the first. My run is different. I'm blazing the trail of a Harlem district that is not just black — it's more multicultural, multiracial. The idea is to bridge those barriers."

There is, perhaps, another factor as well. Instead of coming up through Harlem's political machine, the newest batch of African-American leaders — stars such as Obama, Newark Mayor Cory Booker and Alabama Representative Artur Davis, Rangel's colleague on Ways and Means — have risen through the traditional channels of the U.S. meritocracy, says David Bositis, an expert on black electoral politics at the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies in Washington. "These guys are Ivy league, corporate-law-firm types," Bositis says. "You're talking about a very different political system than what Basil Paterson, Dinkins and guys like that grew up in." Going forward, he adds, there will be "competing centers of black leadership around the country, but they're not going to occupy the same level of status that [Harlem] did."

Perkins says it's inaccurate to characterize a changing of the guard as Harlem's demise. Harlem has matured into a wealthier, more diverse neighborhood that "will continue to be the voice of the black community," he says. Wright, meanwhile, says Harlem's history will prevent it from ever losing its clout. "As far as I'm concerned," he says, "the road to any office, from the President of the United States on down, will always lead through 125th Street."