True Compass

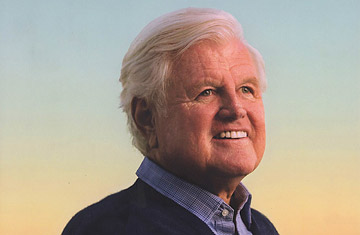

By Edward M. Kennedy

532 pages; Twelve

The Gist:

When Senator Edward M. Kennedy died Aug. 25, it effectively signaled the end of America's most glamorous political dynasty. The Kennedy name has long held almost mythic status in this nation's public life, and Teddy — the youngest of Joseph and Rose's nine children — lasted the longest and suffered the greatest tribulations. The violent and sudden deaths of his three brothers, a plane crash, the scandalous (and, some say, unforgivable) night at Chappaquiddick: all juicy fodder for a memoir. Luckily for the curious, Kennedy had been working on one for two years before his death. It hits bookstores Sept. 14.

Highlight Reel:

1. On fighting off French communists during his time in postwar France as an Army MP — just one of the sticky situations he would get into as a young man: "I could see that their sticks were sharpened at the ends. Pig sticks, used for jabbing at pigs to encourage them toward the pen. Then I remembered that I was armed as well: wrapped around each leg of my MP pants ... was a bicycle chain ... I reached down and unhooked the chains. I started whirling them over my head."

2. On having to inform his father of the death of John F. Kennedy: "I contacted Eunice, and together we rushed home by helicopter and jet. By the time we arrived, the anticipation of what lay ahead had burned through any numbness and replaced it with dread. I fought it by launching myself out of the plane, through the front doorway, and up the stairs to Dad's bedroom. His eyes were closed. I would let him have this last peaceful sleep. The television set near his bed caught my eye. I lunged at the connecting wires and ripped them from the wall."

3. On the aftermath of the assassination of Robert Kennedy: "Life, and politics, went on. But not in the same way. Not for me. I was shaken to my core. I was implored to rejoin the political whirlwind less than an hour after Bobby expired. The activist Allerd Lowenstein found me on an elevator at the hospital and blurted that I was all the party had left. In subsequent days and weeks, Mayor Daley of Chicago led the voices of those who sought to enlist me as a standard-bearer against Richard Nixon. I told them all no. I understood very well the stakes of the forthcoming election. I simply could not summon the will."

4. On the aftermath of the assassination of Robert Kennedy, Part II: "As I walked in a St. Patrick's Day parade in Lawrence in March 1969, a burst of popping firecrackers caused me to freeze in my tracks and prepare to dive to the pavement. I stayed upright by an act of will. Years later, on another occasion, I was enjoying a walk in the sunshine near the Capitol with Tom Rollins — then my chief of staff — when a car backfired down the street. Tom recalls that I was suddenly nowhere to be seen. Turning around, he saw me flattened on the pavement. 'You never know,' Tom recalls me saying. His memory is probably true. Even now, I'm startled by sudden noises. I flinch at twenty-one-gun salutes at Arlington to honor the fallen in Iraq. My reaction is subconscious — I know I'm not in danger — but it still cuts through me."

5. On his car accident on the bridge to Chappaquiddick, an unexplained crash that claimed the life of a young worker on his brother Bobby's campaign, Mary Jo Kopechne — and forever tainted his political career: "That night on Chappaquiddick Island ended in a horrible tragedy that haunts me every day of my life. I had suffered sudden and violent loss far too many times, but this night was different. This night I was responsible. It was an accident, but I was responsible."

The Lowdown:

A tour through both the claustrophobic history of the Kennedy family and the tumultuous latter half of the 20th century, True Compass is clearly Teddy's attempt at burnishing his legacy. In that regard, he is less than successful, though — he often seems more concerned with telling the story of the times than he is in telling the story of his accomplishments (for which he makes a surprisingly anemic case). There's a feeling at points that he's ticking off moments in history, rather than grappling with them. But it's clearly the personal anecdotes that readers will flock to — those rambunctious tales of young adulthood, like bronco-riding in Montana in order to win votes for JFK — although the revelations are few and far between and his latter years were a gauntlet of seemingly endless tragedy. Still, it's a rare example of a political memoir with staying power.

The Verdict: Read