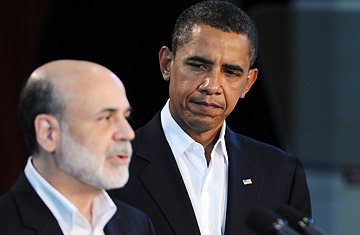

President Barack Obama listens as Ben Bernanke speaks at Oak Bluffs School on Martha's Vineyard on Aug. 25, 2009

Before Ben Bernanke was chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, he was an ivory-tower economist who trained at Harvard and MIT, taught at Stanford and Princeton and may have learned more about the Great Depression than anyone else on the planet. One thing he knew was that he never wanted to see another one.

So when the financial markets melted down in 2008, the mild-mannered, consensus-minded, professorial ex-professor vowed to avoid the errors of omission the sluggish Fed had made in the 1930s and do everything possible to prevent the crisis from becoming a calamity. He blasted a fire hose full of dollars at the U.S. economy, exercising unprecedented powers and sidestepping the democratic process, figuring that desperate times called for desperate measures. And while the blaze hasn't been extinguished, it's starting to look like it's under control, which is why President Barack Obama reappointed Fireman Ben to a second term on Tuesday. Bernanke was at the President's side when he made the announcement and heard Obama say that Bernanke had "led the Fed through one of the worst financial crises that this nation and this world have ever faced."

Bernanke's is in many ways an inspiring story, a financial overlord from Main Street rather than Wall Street, from the faculty lounge rather than the corridors of power, from the realm of pragmatism and analysis rather than partisanship and ideology. He was a nice Jewish boy from small-town South Carolina who had pursued a career of scholarship; before George W. Bush appointed him to the Federal Reserve Board in 2002, his only brush with politics had been a stint on his local school board. Before the markets went haywire, he was building a reputation at the Fed as a collegial and unassuming technocrat who had none of the cult of personality that had swirled around Alan Greenspan — and he actually tried to make himself understood.

Otherwise, Bernanke mostly tried to continue Greenspan's policies, which were wildly popular at the time. But that was before the chaos, before the collapses of Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch, Fannie and Freddie, Lehman Brothers, AIG and WaMu, before Bernanke called upon decades of historical study to start dispensing money to banks and then quasi-banks and then companies that weren't banks at all. In his insider account In Fed We Trust: Ben Bernanke's War on the Great Panic, David Wessel details how Bernanke essentially turned himself into a fourth branch of government, exploiting a loophole in a 1932 law that gave the Fed wide latitude in "unusual and exigent circumstances" to become a virtual economic commander in chief, dropping several trillion dollars into the nation's credit jet stream without presidential or congressional input, inaugurating all kinds of unprecedented programs with obscure acronyms. His motto, Wessel writes, was "whatever it takes."

The Great Recession has not become another Great Depression — the markets have rebounded, and Bernanke declared last week that the worst of the downturn appears to be over — so Obama really had no choice but to reappoint Bernanke, even though White House economic adviser Lawrence Summers has yearned for the job. The markets like stability, and they really like Bernanke. And Obama might have done the same thing even if he did have a choice. Bernanke hasn't been flawless — he was slow to grasp the crisis and start yanking interest rates down toward zero, and market watchers will forever second-guess the decision to let Lehman go under. But overall he's been courageous and innovative and (so far) successful. And while he's fairly new to Washington, he's shown a flair for politics and p.r., doing a memorable 60 Minutes interview at the height of the crisis, providing an important vote of confidence for Obama's stimulus package and getting the theater as well as the substance right at several key congressional hearings.

That said, there's something a bit creepy about the megapower that's accumulating at the Fed, one of Washington's least accountable institutions. Why should the markets decide who oversees them? Haven't the markets decided enough? Bernanke may be the ideal benevolent financial despot — a nebbishy superscholar with minimal connections to Wall Street and no previous hunger for power — but the next Fed chairman may be less ideal. And Obama has proposed to give even more regulatory power to the Fed, even though it has shown little interest in the past in curbing the excesses of the markets. At the same time, any politician who meddles with the Fed gets pilloried for threatening its hallowed independence; it's like the Supreme Court, if the Supreme Court could pour trillions of dollars wherever it wanted.

The Fed chairman is often described as the second most powerful U.S. official; the main check on him is the first most powerful official's power not to reappoint him. That power won't be used this year, and it's easy to see why. But someday, a President may have to use it — no matter what the markets say.