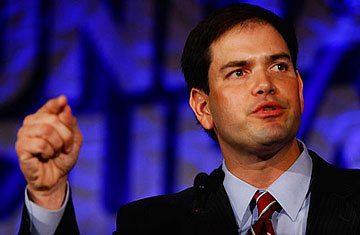

Florida GOP house speaker Marco Rubio addresses Barack Obama, then a presidential hopeful, during a Cuban Independence Day celebration in Miami on May 23, 2008

While his Republican Party has been flailing and losing and dwindling to its base, Florida Governor Charlie Crist has remained extremely popular by governing from the middle. He has stocked his administration with Democrats, appointed a fairly liberal African-American Democrat to the state supreme court, expanded voting rights for felons, crusaded against global warming and enthusiastically supported President Obama's stimulus package. Crist's crossover appeal — along with his powerhouse skills as a fundraiser and campaigner — has made him a heavy favorite to join the Senate in 2010. To some observers, his success in the largest swing state could be a national model for a GOP in the wilderness, proof that the party still appeals to independent voters.

But those observers do not tend to be Republicans, much less the conservative partisans who tend to dominate closed Republican primaries. They've got a different vision for the party's future, and it looks more like Crist's 38-year-old Cuban-American primary challenger, Marco Rubio, a dynamic and telegenic ideologue who was the first minority speaker of the Florida house of representatives and is now described by fluttery admirers as an Obama of the right. He's a passionate defender of traditional Republican principles and wasn't part of the generation of Republican leaders who betrayed them. He speaks for the tea-party base, the limited-government purists who believe the GOP lost favor because its leaders were insufficiently rather than overly conservative. They see Crist as part of the problem, a big-spending, eco-radical, finger-in-the-wind Democrat-lite.

The National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC), thrilled to recruit a proven statewide winner who can raise cash without help from Washington, endorsed Crist the day he entered the race. So did outgoing Senator Mel Martinez, who announced last week that he's stepping down early, allowing Crist to select a sympathetic caretaker — he says he won't name himself — to keep the seat warm. Early polls suggest that Crist would easily beat any Democrat — the favorite is Congressman Kendrick Meek — and that he's starting with a 30-point lead over his GOP challenger. Crist also raked in a state-record $4.3 million in the second quarter, swamping Rubio's $340,000; the media are speculating that Rubio will run for attorney general instead, and his campaign manager and chief fundraiser are already gone.

But Rubio insists he won't drop out, and those daunting polls suggest that the relatively few Republicans who know Rubio are quite likely to vote Rubio. Over the next 14 months, as Rubio introduces himself to the state, this race is likely to evolve from David and Goliath into a struggle for the party's soul, with a moderate populist who celebrated the stimulus with Obama at a Fort Myers rally and a conservative stalwart who opposes almost everything Obama has done.

The NRSC's heavy-handed decision to intervene in the primary has already prompted an anti-establishment backlash by the right-wing blogosphere, and endorsing Rubio is becoming a trendy way for Republicans like 2012 presidential hopeful Mike Huckabee, South Carolina Senator Jim DeMint and former House majority leader Dick Armey to demonstrate their conservative bona fides. Grass-roots Florida Republicans are also refusing to anoint Crist; Pasco County's GOP committee, which supported him against a conservative primary opponent in 2006, backed Rubio this time by 73-9 in a straw poll, and Lee County's Republican activists gave Crist a similar thumping. Rubio did even better in Highland County, whitewashing Crist 75-1.

Crist may be the most popular politician in Florida, but for the Florida GOP, that person would be Rubio's mentor, former governor Jeb Bush. His disdain for Crist's policies is an open secret in the Sunshine State, and his son has endorsed Rubio. Crist will still have a huge advantage in money and name recognition, but when choosing between a Republican and a Republican, Republicans usually pick the Republican. It's the same phenomenon that could doom party-switching Senator Arlen Specter in the Pennsylvania Democratic primary; partisans don't often reward bipartisanship. "Crist has focused on the Arlen Specter wing of the Republican Party," says Palm Beach County GOP chairman Sid Dinerstein. "Rubio could be the future of a real Republican Party."

If you wanted to draw up a candidate for a party that needs to stop alienating young, Hispanic, Catholic and working-class voters and start inspiring its dispirited base of fiscal and social conservatives, Rubio would be it. He's the son of Cuban exiles, a bartender and a hotel maid who raised him to remember that faith matters, work pays and politics can stifle liberty in a big way. He's married to a former Miami Dolphins cheerleader, and he's got four young children. He's only 5 ft. 9 in. and 160 lb., with a sweet-faced earnestness that is unusual in politics; after he was elected to the state legislature from West Miami at age 29, a state official, mistaking Rubio for an intern, sent him to make copies. But he's also tenacious and ambitious, and with Bush's support, he rose to the speaker's chair in 2007; the ceremony was broadcast live in Cuba on Radio Marti.

Rubio quickly built a reputation as an idea guy; he held a series of "idea raisers" around Florida, and the conservative Regnery published his subsequent book, 100 Innovative Ideas for Florida's Future. As speaker, he pushed dozens of those ideas through the house, but few of them made it past Crist's desk. For example, Rubio pushed for radical tax reforms that would have virtually eliminated property taxes; he had to settle for Crist's relatively modest cuts. Rubio also filed a lawsuit to try to stop Crist from expanding Indian gaming; the governor won that battle too.

Rubio is not a chest thumper or a fist banger, but in talks in June to a chamber of commerce in Palm Bay and the Christian Coalition in Miami, he electrified the crowds with eloquent arguments for tea-party principles. He attacked deficits in general and the stimulus in particular as Euro-socialist assaults on his kids. He clamored for term limits, states' rights and the abolition of the estate tax. He attacked government-run health care, warned that cap and trade would leave us with a "Third World economy," and noted that the words "separation of church and state" were nowhere in our founding documents. At times, he seemed to sense that he sounded extreme and offered clarifications like "I'm not saying Barack Obama is the same as Fidel Castro" and "I'm not an anarchist."

He isn't, but he is a savage critic of big government; he sees the crucial divide in politics as between those who trust the public sector to grow the economy and those who trust "the guy drawing up a business plan on the back of a napkin at Denny's." In an interview, he supported the privatization of Social Security, a constitutional amendment to restrain spending and the right of schools to teach intelligent design. He sees the stimulus as a defining issue, an inexcusable embrace of intergenerational theft that exposed Crist as a Specter-style Republican In Name Only. If the Republican Party is going to be indistinguishable from the Democratic Party, why bother having one? he asked.

Rubio rarely mentions Crist by name, but he has asked why the GOP would want a clone of Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins of Maine, the last moderate Republicans left in the Senate. His favorite campaign theme is popularity vs. leadership, an unsubtle dig at Crist's over-60% approval ratings. He has repeatedly accused poll-driven Republican leaders of abandoning their principles and selling out the grass roots in pursuit of power, letting focus groups and Beltway pundits tell them what to do. "In normal times, that's annoying," Rubio said. "Right now, it's dangerous."

But while Rubio is clearly a fresh face, he's not really pushing fresh ideas. He constantly invokes Ronald Reagan and traditional values but seems uncomfortable with modern problems. His solution for the energy crisis is for government to butt out so that someone can invent a tiny battery that will power a whole city. The only specific critique he made of U.S. health care was that hospitals don't say how much their appendectomies cost, as if patients in acute abdominal pain are looking to comparison-shop. He tweeted that the situation in Iran would be different "if they had a 2nd amendment like ours."

That's a compelling message for the base. And as centrists have fled the party, the base has become increasingly dominant within the GOP, which is why Crist is now scrambling to the right; he surprised many supporters by opposing Sonia Sotomayor's nomination to the Supreme Court and signing a developer-friendly bill to weaken growth-management laws. But it's not clear how much of the base will accept Crist's last-minute embrace. And if popular centrists like Crist can't win primaries, moderates will keep fleeing, the vicious cycle will continue, and the party will be in trouble. "The governor is a problem solver above all else," says Crist's political strategist, George LeMieux. "He's a national model of a Republican leader who serves all the people, not just his party."

In the modern Republican Party, that's a problem. Crist has one year to solve it.