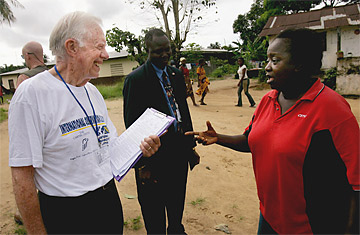

Jimmy Carter in Monrovia, Liberia, where he went to help monitor its elections with the National Democratic Institute in 2005.

At noon on Jan. 20, Barack Obama will take the oath of office and President George W. Bush will cease to be the most powerful person in the free world. Instead, he'll become a guy who might be the most powerful person in the wealthy Dallas enclave his family is moving to after Washington. Might be. So what's a former president to do? Bush has said he's going to work on his library, write a memoir, and earn some bank on that mythical "speaking circuit" that has proved so remunerative for Presidents past. His immediate predecessors include two astoundingly productive ex-presidents (Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton), some lackadaisical ones (Gerald Ford, George H.W. Bush), a disgraced lion in winter (Richard Nixon) and a man who, in hindsight, was likely in the emerging stages of a devastating sickness (Ronald Reagan). But America has had many presidents over the centuries (43, last time we counted) who generally fall into several, non-exclusive categories:

The Farmers:

Early presidents were often landholders and George Washington set a precedent by retiring to his Mount Vernon plantation after leaving office in 1797. John Adams went back to his Massachusetts farm, Thomas Jefferson settled at Monticello, James Madison kicked back at Montpelier, Andrew Jackson went down to his plantation near Nashville and Martin Van Buren took it easy at his farm, Lindenwald. John Tyler settled into a relaxed life at his Virginia plantation, Sherwood Forest. Then he joined the Confederate Congress, essentially becoming a traitor to the nation he once led. (See pictures of how Presidents age in office.)

The Memoirists:

James Buchanan basically started this trend, with 1866's instantly forgettable Mr. Buchanan's Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion, a partial attempt to shift blame for the causes of the Civil War away from his administration. Later the 18th president, penniless and deathly ill in his final years, negotiated a deal with publisher Mark Twain to write the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, a two-volume set that is still considered one of the best presidential memoirs ever penned. In 1913, Theodore Roosevelt wrote another well-regarded tome (predictably, and straightforwardly, titled Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography). Harry Truman wrote his memoirs because he was broke, Herbert Hoover produced his in an attempt to improve his Depression-tarnished image, and it's been sort of downhill ever since, culminating in Bill Clinton's 1,000-plus page apologia My Life. (See pictures of Presidents giving State of the Union addresses.)

The (Sometimes) Happily Ever Afters:

Some Presidents were content to retire from public life by the end of their terms. Millard Fillmore spent the rest of his days in quiet anonymity (as he had spent his time in the White House, detractors say). Calvin Coolidge did little better. Eisenhower golfed (hole-in-one at the age of 77!) and LBJ hung out with his grandchildren. Others, however, found the strain of high office to be too much. James K. Polk died three months after leaving the White House. Franklin Pierce, whose 11-year-old son had been killed in a train accident just weeks before his inauguration, drank. And Chester A. Arthur died about 18 months after his term ended.

The Perpetual Office-Seekers:

It's hard to let go sometimes, and some men have attempted to regain the nation's top spot. Martin Van Buren, whose term ended in 1841, ran again twice for the presidency, once in 1844 and again on the Free Soil ticket in 1948. (He lost.) Teddy Roosevelt, in between African safaris and expeditions to uncharted Amazonian rivers, ran for a third term on the Bull Moose ticket. He was shot right before a campaign stop, yet was hearty enough to deliver his speech with the bullet lodged in his chest. (Still, TR lost.) Millard Fillmore ran a disinterested campaign for the Whigs. (Did not win.) Grover Cleveland, however, was victorious: in 1892, three years after leaving office, he became the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms.

The Perpetual Office-Holders:

Some ex-presidents proved to be more effective public servants after the White House than before. John Quincy Adams served nine consecutive terms as a congressman and argued the Amistad case (made famous by the Steven Spielberg film) before the Supreme Court. William H. Taft became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court following his unimpressive term. He loved the job so much that he was said to quip, "I don't remember that I was ever president."

The Activists:

Carter and Clinton aren't the first ex-presidents to take an interest in the greater good. Rutherford B. Hayes became president of the National Prison Association after taking notice of the atrocious living conditions most imprisoned Americans endured. Herbert Hoover, reviled for years because of his contribution to the Great Depression, earned a second chance when Harry Truman asked him to head the Famine Emergency Commission — responsible for distributing food to nations devastated by World War II — and another commission tasked with reorganizing the government and eliminating waste. President Carter, of course, established the Carter Center, devoted to supporting human rights around the world and won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts; the 42nd President's Clinton Foundation, meanwhile, has concerned itself with eradicating AIDS in Africa. (See pictures of former Vice-President Al Gore.)

The Rest:

Harry Truman, who became the holder of the first Medicare card for his support of the legislation, also succeeded in getting a bill passed in 1958 that provided former presidents with a pension, staff, and office space. Prior to that, ex-presidents received no such retirement benefits (Truman was fairly broke when he left office). And finally, Richard Nixon mediated a baseball umpire's strike in 1985. We don't know what to make of that either.