Eric Holder figured the call could wait. His pager had gone off in the middle of a Washington Wizards game on Jan. 14, 1998. But when a second page came in at 10:18 p.m. with a message marked "Urgent," the then Deputy Attorney General decided to call back. "What's up?" he asked Jackie Bennett, principal deputy to Independent Counsel Ken Starr.

"We're sort of into a sensitive matter" involving "people at and associated with the White House," replied Bennett. (See the Top 10 unfortunate political one-liners.)

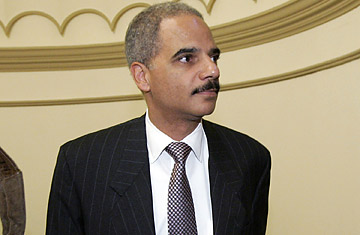

That vague exchange launched a criminal investigation that resulted in Bill Clinton's impeachment and perhaps the most rigorous test of Holder's career. Nearly 11 years later, he is reported to be President-elect Barack Obama's first choice for Attorney General. Transition aides, and much Washington speculation, have focused on Holder's brief part in Clinton's controversial last-minute pardon of fugitive tycoon Marc Rich as a potential snare in confirmation hearings. But the behind-the-scenes role Holder played in the Monica Lewinsky probe — a 10-month Justice Department ordeal — offers a much fuller record to scrutinize. And like everything else with that polarizing scandal, Holder's shifting positions at the time are likely to be judged differently depending on one's view of Clinton and Starr.

The high-stakes political-legal drama obscured Holder's role at the time, but details emerged in later reporting for a book, Truth at Any Cost, that I co-authored with Susan Schmidt. That account was based on interviews with Starr, his staff and senior Justice Department officials, including Holder — as is this article.

On that night of Jan. 14, Holder demonstrated the kind of apolitical open mind he was known for as a local judge and U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia. Named to the DOJ's No. 2 job a year earlier, he served as the contact point for the sprawling independent-counsel probes commissioned by his boss, Janet Reno, into everything from an Arkansas land deal to the firing of the White House's travel office. So when Bennett asked for a meeting late the next day, Holder quickly acceded with an invitation to his office.

The subject was explosive. Two days earlier, Bennett had received a phone call from a Maryland woman named Linda Tripp, who said her friend Lewinsky had had an affair with Bill Clinton, and that superlawyer Vernon Jordan was trying to land her a job to buy her silence in the ongoing Paula Jones sexual-harassment suit against the President. The story rang a bell with the prosecutors, who had been pursuing evidence that Jordan helped obtain a lucrative consulting contract for another Clinton pal who was a potential witness in the Whitewater land-deal probe. Starr's team had heard enough from Tripp to wire her up for a planned meeting on Jan. 13 with Lewinsky, who ended up confiding more damaging information about Clinton: she claimed he had told her he planned to deny their affair in a deposition by Jones lawyers four days later.

Uncertain how to proceed, Starr decided to defer to the DOJ, prompting the Holder meeting, which took place at 6 p.m. on Jan. 15. The deputy AG sat in silence as he heard the allegations. He knew they had to be investigated quickly. The question was by whom. His own department, run by Clinton appointees, had an obvious conflict. A new independent counsel could be brought in, but not in time to gear up for the President's Jan. 17 deposition. He saw no alternative but to let Starr's office carry the ball. Reno formalized the decision on Jan. 16.

The DOJ's top lawyers believed Holder made the right call legally — he had no real choice, given the facts presented by Starr's deputies. But Clinton aides were livid. After years of strained relations with Reno and the six independent-counsel probes she had initiated, Holder had been viewed as someone they could deal with. The deputy had successfully urged Reno not to launch a seventh probe into questionable fundraising practices by Clinton in his 1996 re-election campaign, resisting pressure from Congress and DOJ career lawyers. Holder, in fact, looked like he was being groomed for the top job if Reno decided to step down before Clinton left office. Now his bright prospects dimmed. Clinton allies questioned how he could have recommended Starr to run the most threatening of all investigations of the President. (See pictures of presidential First Dogs.)

Holder seemed deflated by the criticism but determined to recover his reputation among Clintonites. He approved the DOJ's legal backing of a unique privilege that the Secret Service claimed early on to keep its agents from testifying before the grand jury about Lewinsky's visits to the Oval Office — a legal ploy that Holder privately acknowledged to Bennett was a long shot, and which was ultimately rejected by federal courts.

The deputy AG acted more subtly in February after Clinton lawyer David Kendall charged that Starr's office had leaked grand-jury information. When Starr announced plans for an internal investigation of the leaks, Holder advised him to stand down until the federal judge overseeing the case found merit in the complaint. But at the same time, Holder quietly called the judge and offered the DOJ's help in pending issues raised by the President's lawyers, which included the leaks question. When Starr learned about the unusual intervention, he saw it as a betrayal. (Holder has denied that he "ever encouraged the judge to move forward the matter involving alleged leaks to the Justice Department.")

From the outset, Clinton's lawyers sought to discredit the Lewinsky investigation as a witch hunt by right-wing lawyers headed by Starr, who, while not politically active, was a conservative Republican. Holder never publicly endorsed that view but fanned it by drawing public attention to similar allegations in the Whitewater case: a prosecution witness had supposedly received payments by anti-Clinton philanthropist Richard Mellon Scaife to discredit the President. In April, Holder wrote to Starr, urging him to look into the matter, and then released the letter to the press. The accusation rested on shaky stories by questionable sources, but the DOJ's public spotlighting of it undercut Starr's credibility as he was trying to get to the bottom of the Lewinsky matter. With Reno's approval, Starr asked a seasoned ethics lawyer to look into the charges, which he ultimately dismissed as false.

Although Holder did not subscribe to the devil theories of Clinton's lawyers, he questioned whether Starr's deputies had manipulated him into approving the Lewinsky probe. As his view of the case darkened, so did his relationship with Bennett, a decorated career prosecutor who had worked with Holder at the DOJ when they were young lawyers and played pickup basketball together. Bennett had come to believe his old friend was undermining the investigation. The mutual bitterness came to a head at a March 20 meeting in Holder's office.

Bennett complained angrily that after authorizing Starr's office to investigate the Lewinsky case, Holder's department had done nothing to defend the prosecutors, including longtime assistant U.S. Attorneys on loan to Starr's office, from harsh personal and professional attacks by Clinton's lawyers.

"You guys are just too thin-skinned," Holder shot back. "This is the big leagues."