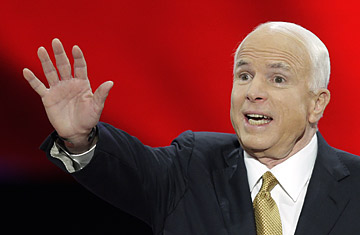

Republican presidential nominee John McCain waves while making his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention

With both national and battleground-state polls showing John McCain losing ground to Barack Obama in recent weeks, the Republican presidential nominee is getting a lot of unsolicited advice. Party professionals around the country are publicly calling on McCain to change the subject from the nation's faltering economy by becoming much more aggressive in his attacks against Obama. Go after the Illinois Senator on his ties to his controversial former pastor, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, some urge, or attack Obama's associations with convicted Chicago real estate developer Tony Rezko or former '60s radical Bill Ayers.

But even if such attacks could potentially give McCain a brief boost, it's not at all clear that they would help for the long haul. After all, since midsummer, the Arizona Senator has effectively dominated the day-to-day media narrative through a series of surprising, bold and, to some, reckless tactical moves designed to keep his opponent on the ropes. Through depicting Obama as Paris Hilton, selecting the little-known governor of Alaska as his running mate, manufacturing the lipstick-on-a-pig contretemps and, most recently, "suspending" his campaign to tend to the financial crisis, McCain has consistently garnered headlines and forced his opponent to respond.

Each of the bold moves brought McCain short-term political gain, throwing the normally unflappable Obama off his stride and keeping the Republican nominee very much in the presidential hunt in a dismal year for Republicans. But the tactics also contained the potential for long-term political costs by distracting from, or eroding, the central McCain message. By comparing Obama to a vacuous Hollywood starlet, McCain found a coherent critique of Obama but relinquished his own ability to rise above the political maw. By choosing Sarah Palin, he lit a grass fire of GOP enthusiasm but risked undermining his ticket's claim of having greater experience and putting "country first." By attacking Obama's "lipstick on a pig" comment, the campaign clearly established itself as willing to engage in frivolous, small-ball distractions, a disposition that served McCain poorly when he pivoted and tried to portray himself as a sober statesman willing to halt his campaign to deal with the nation's financial meltdown. Most recently, McCain rolled out an ad calling on a new spirit of bipartisanship and cooperation in the nation's capital only a day after blaming the House of Representatives' defeat of the Administration's bailout bill on Democrats and Obama.

"The well of false sanctimony is not a bottomless pit," explains one Republican consultant. "I think they have reached the bottom of the well."

By far, McCain's boldest move was selecting Palin, a governor with scant national experience. For a few weeks, the gambit seemed to pay off handsomely. White women voters overwhelmed campaign events and boosted the ticket's poll numbers. But doubts about Palin's qualifications and competence remained unanswered, and after a series of stumbling television interviews, voters — and even some conservatives — have begun to sour on her. "Everyone was high-fiving each other after they picked her because their goal was to steal Obama's momentum for a week," says a second GOP consultant, who also did not want to be named while criticizing the campaign. "Well, they did that. Now look what they've got."

Given the country's current harsh view of the Bush Administration and Republicans in Congress, McCain could be doing far worse. Counted out for much of the summer, the campaign operation, under the leadership of Steve Schmidt, has managed to run consistently ahead of the Republican brand. The campaign's top brass, meanwhile, remains unapologetic about its risk-taking approach and undaunted by the odds. "We would have packed up the tent four months ago if we didn't like daunting challenges," says Mike Duhaime, the campaign's ground-operations chief. McCain, as well, has been unapologetic about the moves his campaign has made, often comparing himself to his role model, Teddy Roosevelt. "I am a betting man," McCain recently told NBC News.

But more and more of his moves look like losing bets. Even before the first presidential debate ended, McCain's campaign posted an attack ad online highlighting Barack Obama's repeated admission on the shared stage that McCain was "absolutely right." On its face, the spot seemed like damaging proof that Obama is a wishy-washy follower, not a clear leader. But both Democratic and Republican strategists were puzzled. Why was the campaign cutting a spot that undermined the claim that McCain invites bipartisan agreement? Do they now suddenly scorn consensus? "They got the tactic right, but the message was off," observes one Republican campaign consultant. An Obama spokesman, Tommy Vietor, described the YouTube spot more succinctly. "It helped us," he said.

The deeper problem, say growing numbers of worried GOP establishment types, is that while lurching around to win the daily and weekly news cycles, McCain has failed to give voters a broad, forward-looking explanation for why they should support him. McCain's national-security experience and reputation as a reformer add substance to his theme of "putting country first," but they don't explain what a McCain presidency would mean, or how it would differ from the past eight years. "At no point have they told the American people where John wants to lead them," says a third Republican strategist. "Had they spent more time laying the predicate, they'd have something to fall back on now."

McCain formed his unorthodox plan for winning the White House in the dark days of midsummer, during a time when his campaign was defined by small crowds, logistical missteps and an inability to break through the media's fascination with Obama. At the time, McCain's aides openly vented their frustration, both with the political climate, which favored Democrats, and with the media, which they believed had unjustly soured on McCain. It was an environment that seemed tailor-made for Schmidt, McCain's new day-to-day campaign manager, who had earned his stripes in the hardscrabble world of the Bush-Cheney 2004 war room, fighting and winning the news-cycle battle.

The plan Schmidt developed for McCain called for the campaign to go on offense, with sometimes shocking moves that would begin winning weeks of news coverage. Call Obama an unprepared celebrity. Reintroduce McCain as a maverick and a change agent. Hit old Republican themes on taxes and spending. Run away from the record of Republicans in Congress and the White House. Make copious use of outrage and emotion. Rather than a single, unified message, Schmidt planned a multifaceted attack, which would be stitched together under the banner of "Country First," a phrase that both highlighted McCain's war-hero biography and suggested Obama was a selfish, pandering elitist.

At the same time, campaign aides laid out benchmarks for success. "I outlined the campaign this way: We need to be tied before the conventions; we were," says Bill McInturff, McCain's top pollster. "We need to be ahead after our convention; we were. We need to be roughly tied at the debates." After that, however, McInturff told his candidate, the campaign was a "black hole."

The entire strategy rested significantly on the McCain campaign's ability to keep disrupting the political discussion. If people questioned Palin's credentials, attack the media. If talk turned to the economy, attack Obama for proposing to raise some taxes. If the news cycle slowed, release a new advertisement, more controversial than the last.

But in mid-September, the plan was disrupted by real-world events. The financial crisis now knocking over banks and rocking the world economy forced McCain to shift gears. His big gambit — suspend the campaign and return to Washington — was undercut from two sides. First, upon arriving he found he had very little power to win votes for the deal or shape the negotiations. In fact, House Republicans voted against the initial package he supported by a margin of 2 to 1. Second, many viewed his decision to suspend his campaign as little more than yet another gimmick designed to grab press attention.

Now the campaign is trying to regain its footing once again. The first part of the "black hole" that McInturff predicted has turned out to contain — at least initially — a nosedive in the polls for McCain. He now trails in several swing states where he led after his convention, and has relinquished some gains he had made with independents and women voters. Like so many times before, McCain finds himself in a crisis situation, facing an uphill battle for the prize he has always sought. This is his political comfort zone. The betting money says he will make a bold move, and hope it doesn't backfire.

(Click here for photos of John McCain on the campaign trail.)