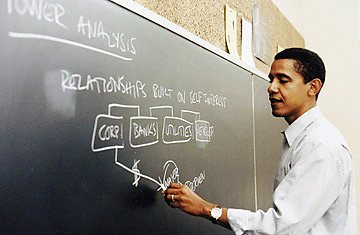

Barack Obama teaching at the University of Chicago Law School

(2 of 2)

Beyond the classroom, Obama was an enigmatic figure at the law school, a bastion of conservative legal and economic scholarship that reveled in debate. He continued to teach even after becoming an Illinois state legislator, and perhaps because of the nearly four-hour commute to the capital of Springfield, Obama rarely attended the school's afternoon meetings, during which instructors and students discussed and argued a range of topics. To some degree, Obama's absence from those meetings isolated him from the highly opinionated scholars who were residents on campus, leading some to see it as an aloofness from a person with a too self-assured worldview. Richard Epstein, a Chicago professor and one of the nation's leading libertarians, sees a parallel with Obama's campaign style. When Obama grants audiences to adversaries, Epstein says, "he's got this wonderful manner, cocks his head forward, always asks good questions. You always feel you've been heard out." But in the end, "he doesn't change his mind. He's surprisingly rigid, intellectually."

Yet the school administration appeared to adore him, even when he began basically working part-time, with most of his week spent in the state capital. He had been reluctant to take the University of Chicago job in the first place, planning to do community work and write a book on civil rights law. But Douglas Baird, then chair of the law school's faculty appointments committee, convinced Obama to take a two-year post as a law and government fellow, promising him an office and time to work on his first book. Baird figured that "he'd be around, in case we could persuade him. [Then] we'd have the upper hand on the other schools that'd want to recruit him."

By the mid-1990s, however, Obama had published Dreams from My Father and was contemplating a career in politics. Baird, by then the law school's dean, recalls Obama walking into his office one day to announce that he planned to run for the Illinois state senate. "It's a bad idea," Baird recalls telling Obama. "You have great talents. You should think about joining the faculty." He recalls Obama saying, "That's not who I am. I want to try politics." Their arrangement: Obama was to become a senior lecturer, a title that put him on the same tier with accomplished attorneys like Frank Easterbrook and Richard Posner, both of whom had become federal judges. The promotion provided Obama with a larger office and a salary higher than that of most other senior lecturers. It became a platform for him to plot his bigger moves — including eventually leaving academe entirely for politics.

In his book The Audacity of Hope, Obama writes: "I loved the law school classroom: the stripped-down nature of it, the high-wire act of standing in front of a room at the beginning of each class with just blackboard and chalk, the students taking measure of me, some intent or apprehensive, others demonstrative in their boredom, the tension broken by my first question — What's this case about? — and the hands tentatively rising, the initial responses and me pushing back against whatever arguments surfaced." Professor Obama is facing a classroom the size of America now. The question is whether he'll be able to bring his students along.