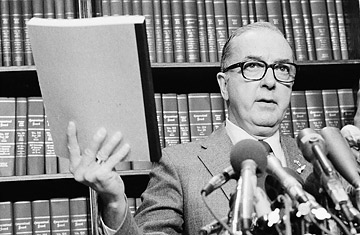

Jesse Helms talks with reporters about a nickel-a-gallon gas tax in 1982.

There's a special place in the United States Senate for the skunk, the single-minded dissident who refuses to go along with the gang and instead uses stubbornness, tenure and the chamber's arcane rules to advance himself and his causes. In the modern Senate, no one played that role as effectively as Jesse Helms, who died early Friday in Raleigh, N.C., at 86. For 30 years, Helms took controversial, sometimes outrageous positions on race, foreign relations and the culture wars, courting controversy and infuriating rivals but often outmaneuvering his centrist and liberal rivals. In the process, he also rewrote the way Americans elect their Senators by transforming his notoriety into mountains of campaign cash and a narrow but motivated grassroots majority in his home state.

Helms was born in 1921 in the small town of Monroe, North Carolina, where his father was police chief and once a year the residents left flowers on the graves of Confederate war dead. Helms dropped out of Wake Forest College and later served as a recruiter for the Navy, which he joined in 1942. After the war he moved into journalism as an editor for local papers but found his true home as an outspoken editorialist on WRAL, a Raleigh-Durham radio and television station. For more than 20 years, long before Rush Limbaugh or Michael Savage, Helms prospered as a media scourge of liberal America. He railed against desegregation, opposition to the Vietnam War, communism, "socialized medicine" and limitations on prayer in schools.

But Helms only really came into his own when he was elected to the Senate in 1972. As North Carolina's first Republican Senator since reconstruction, he was never a shoe-in, but from early on he found a slim majority that would respond to his brand of right-wing politics. He opposed Henry Kissinger's nomination as Secretary of State by Richard Nixon because he thought Kissinger was too soft on communism. He attacked foreign aid as wasteful and ill-considered and he was a central player in the culture wars of the '80s and '90s as the champion of cutting funding to what he considered to be obscene art. Perhaps his most controversial position was as the vocal and stubborn point man against the creation of Martin Luther King Day. "The legacy of Dr. King was really division, not love," he said at the time, and he labeled King an "action-oriented Marxist".

Yet while Helms was portrayed as a racist, a red-baiter and a rube by liberals, he exploited their outrage with tactical brilliance, remaking modern political campaigning in the process. For his first reelection campaign in 1978 he broke the fundraising record, pulling in $7.5 million. In 1984, he broke the spending record for a campaign with an outpouring of $18 million to eke out a 3% win over Governor Jim Hunt. He raised that money both through his national exposure and by becoming one of the first and certainly the most effective user of direct-mail solicitation and campaigning. At various points he hired and advanced the careers of such well-known conservative operatives as Lee Atwater, Charlie Black and Richard Viguerie.

Despite his fearsome national and international reputation, Helms was also known for acts of personal thoughtfulness. When he retired in 2002, North Carolina's junior senator, a Democrat with whom he had often tangled, was among those paying him tribute: "The people of North Carolina will never forget the work and the kindness and the personal attention that he has given to them," he said. John Edwards knew that from experience. Before Edwards ever entered politics, Helms heard about the death of his teen-age son, Wade, in a car accident and went to the floor of the Senate to enter into the Congressional Record an essay that Wade Edwards had written about the meaning of patriotism

Helms was not above working with apparent enemies, and he was open to a light touch. Madeleine Albright famously convinced him of the wisdom of paying America's U.N. arrears and of supporting the Chemical Weapons Convention. And Bono managed to help change his mind about aid to Africa. Helms remained vigorously protectionist to the end, however, and protected North Carolina's tobacco interests throughout his career with equal vigor. But with more than a few lone dissenting votes in the Senate over 30 years, including his opposition to popular nominations and education bills, he'll be remembered mainly as the man who personified the hard right, no matter how unpopular the cause, and even when many of his Republican colleagues in the Senate wished he wouldn't.