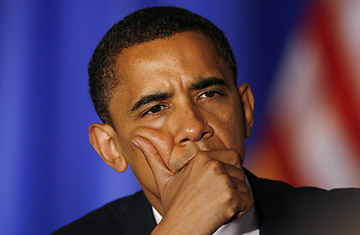

Obama listens to Democratic governors during an economic discussion on June 20 at the Chicago History Museum

To some observers, Obama's transformation from upstart candidate to presumptive nominee has made him begin to look dangerously like the typical Washington politicians he so often rails against. Worried about his patriotism? He now wears a flag pin daily. Worried about his church? He left it. Think he's inexperienced? Don't fret; he's got lots of renowned advisers. Too liberal? Well, just look at his recent policy statements on defending Israel and protecting warrantless wiretapping. And for a man who last week flip-flopped on his pledge to stay within the public financing system, Obama's planned meeting tomorrow with Hillary Clinton's fat-cat donors seems to be his way of saying, "I may not like your game, but I'll take your money."

Certainly this kind of seasonal shifting of messages isn't new for a presidential campaign, in which candidates typically move to the fringes to appeal to their party's all-important base in primaries and the center to appeal to crucial moderate and independent swing voters in the general election. Richard Nixon practically perfected the transformation in 1968, initially building his "silent majority" of conservatives freaked out by hippie war protesters and inner-city riots before selling his "secret plan" to end the Vietnam War in the fall. But having spent the last 16 months pledging to be "the change you can believe in," Obama faces an especially delicate balancing act in playing to the center. Currently Obama trails John McCain among independents not leaning toward either party by a margin of 26% to 35%, according to a June 5-10 Gallup poll.

Obama's risky metamorphosis began before he'd even locked up the nomination. On April 29 he denounced his former pastor, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, whom he once said he could "no more disown than I [could] my white grandmother," after Wright spent a week making even more inflammatory statements to the press than he'd made from the pulpit. And on May 30 — the same day that the DNC's Rules and Bylaws Committee effectively sealed the nomination for Obama — the Illinois Senator quietly resigned from the church he'd been a member of for more than 20 years.

Since becoming the presumptive nominee, nearly every step Obama has taken seems to underline the message that his brand of change is not threatening or even revolutionary. His first general-election ad, "Country I Love," is a 60-sec. paean to his Main Street normalcy. In it Obama extols policies designed to reach across the aisle, such as "cutting taxes" and "moving people from welfare to work." His initial choice of Washington power broker Jim Johnson to run his vice-presidential search was also traditional: Johnson had done the same job for John Kerry in 2004 and Walter Mondale in 1984. Unfortunately, Johnson was a little too old-school — his ties to the subprime loan industry forced him to resign. The campaign this month released a new roster of foreign policy advisers that includes many old, comforting names from the Clinton years, such as former Secretaries of State Madeleine Albright and Warren Christopher. But in some ways Obama has boxed himself in: in trying to counter criticisms about his experience, he's brought in a team full of gray-haired advisers who, by dint of their long-established positions and Washington relationships, represent the furthest thing from change.

The shift hasn't just been cosmetic. The liberal blogosphere lit up angrily when Obama signed on to a controversial Senate compromise to authorize President George W. Bush's warrantless wiretapping programs last week. Earlier this month, Obama conceded that his own rhetoric on trade during the primaries was "overheated and amplified" and that he supports "opening up a dialogue" with trading partners Canada and Mexico on "how we can make this work for all people," as he told Fortune. And in his first speech after cementing the nomination, Obama assured the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, a prominent Jewish group, that he would like to see Jerusalem "remain the capital of Israel, and it must remain undivided," a surprisingly hawkish declaration that outraged the Arab world and Arab-Americans and appeared to contradict earlier statements he had made. He seemed to recognize his overreaching the next day, when he dialed back his rhetoric and told CNN that the fate of Jerusalem should be decided by Israelis and Palestinians through the peace process.

To be fair, Obama is not alone in his calculated repositioning. McCain, the Republican presumptive nominee, has been going through a similar process, struggling to reclaim his maverick mantle after he spent much of the primaries proving his conservative credentials by flip-flopping his positions on tax cuts and immigration.

Unlike McCain, however, no amount of careful brand positioning will stop an Obama presidency from signifying undeniable and historic change: he would be the first black President, the first Democrat in the White House since Bill Clinton and the first President of his generation. He has already revolutionized the way people donate to, and help organize, campaigns. All of which means that Obama faces a unique political challenge. As he tries to maintain the fervent grass-roots enthusiasm that has gotten him this far while appealing to enough independents to take him to the White House, the Illinois Senator must both disprove and prove the old adage that the more things change, the more they stay the same.