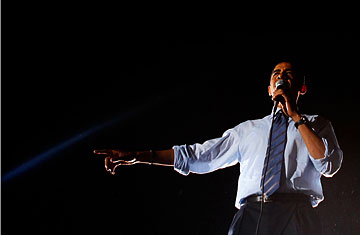

Senator Barack Obama at a rally in Indianapolis on May 5, the day before Indiana was set to go the polls

Throughout the earliest months of his amazing rise as a presidential candidate, Barack Obama showcased an uncanny ability to turn an attack against the attacker. His pre-primary wonkiness last summer became his post-partisan problem-solving by mid-autumn. His inexperience ahead of Iowa became his newcomer's agency for change after his victory there. The question of race in South Carolina soon became a chance for the whole country to rise above it. And after a while, Obama's knack for rebounding created a magical aura around his campaign: the more he did it, the more he seemed to have that indefinable ability to win, no matter the odds.

But if Obama was once rubber to Hillary Clinton's glue, his former pastor's inflammatory remarks and his San Francisco gaffe on working-class bitterness now are sticking to him—fast—as polls show white blue-collar voters harboring serious doubts about his candidacy. So on Monday, a day before the primaries in North Carolina and Indiana, the last question Obama took at a "town hall" meeting got to the heart of the matter. Diana Allen, 39, an employee of LED light manufacturer, CREE, who identified herself as an undecided Democratic voter, said the most important thing for her was victory. So, she asked Obama, what can you say about how you would win the election in November?

Obama rolled out his familiar themes in answering Allen's question. This time last year, he said, no one thought that a black guy named Barack Obama was going to beat the best Democratic brand name, the Clintons. "The problem," he said, "is once you're a front-runner, it's the obligation of the candidates who are behind to try and whack you over the head." He acknowledged the furor over his former pastor's comments and his own San Francisco statements, but he said, there's something about his campaign "that's right, that's true." More pointedly, he argued that when he goes up against the putative Republican nominee, Sen. John McCain in the fall, the party will put aside its current differences, unite behind him and against what Obama called a continuation of George W. Bush's policies.

The exchange about electability underlined the key issue that will be read into Tuesday's results. Since Obama has an almost ironclad lead in popularly elected delegates, Hillary Clinton's only remaining hope lies in the possibility of enough superdelegates deciding Obama can't beat McCain. If he somehow loses both his North Carolina stronghold and Indiana, where the polls are split but Clinton has momentum, that scenario will still be possible. Reagan Democrats fearing the connection to Rev. Wright's fiery rhetoric and the supposed elitism of Obama's San Francisco comments will appear to have irrevocably fled to the camp of anyone but Obama. If on the other hand Obama manages to win both, he'll have relearned the art of political levitation, and Clinton likely will have to drop out of the race. But if, as most observers expect, Clinton and Obama split the decision, the post-primary spin will rotate around what the margins of victory seem to say about Obama's ability to win in November.

Still, for all the focus on electability, there are some aspects of the analysis that are left unspoken. In his town hall response, Obama delicately avoided directly addressing what some say is the coded message behind "electability": that it's actually just a stand-in for race, and for whether the country is ready to elect a black man President. That, after all, is the stake that Rev. Wright's outbursts have put on the table, and in a way it's the question that's been there from the start of Obama's campaign. Obama's aides likewise won't directly address the question: I asked both his communications director Robert Gibbs and his chief strategist David Axelrod if "electability" was code for race. They both ducked the question.

Campaign allies are less restrained when they talk on background. One key Indiana player said the Clinton camp, by questioning Obama's electability, had been "blowing the dog-whistle on race" in Lake County, which helps make up northwestern Indiana's 20%-25% of likely Democratic primary voters. He and other Indiana aides say Clinton surrogate attacks on minority-focused get-out-the-vote efforts in the region were racially based. Others said Clinton's choice of venues, especially "white flight" towns in southern Lake County, were chosen to send racial cues, and to target fertile ground for the coded message of "electability."

Clinton campaign aides vociferously deny the accusation. And indeed, some of these suspicions may be calculated spin by the Obama camp. One of the ways Obama managed his early political artistry was to turn every Clinton criticism, even fairly innocuous ones, into an unacceptable expression of the old, broken politics of Washington D.C. Now, though, whether because of the length of the campaign or Obama's own shortcomings as a candidate, that line of argument has less traction.

On the other hand, the Clinton camp has to be careful. As evidenced by the reaction to Bill Clinton's Jesse Jackson comments, South Carolina showed that if they are perceived to be blowing the race "dog whistle" it can hurt them, and bad. At least one uncommitted superdelegate in North Carolina said this week that pushing that button could push him away. "I do expect Sen. Obama to be the nominee," Brad Miller, the Congressman from North Carolina's 13th congressional district, told me Monday morning at his campaign office off an underground garage in downtown Raleigh. "And if 'electability' is code for being African American," he said, "I can't vote against him: I can't justify it to my African-American constituents or to myself."