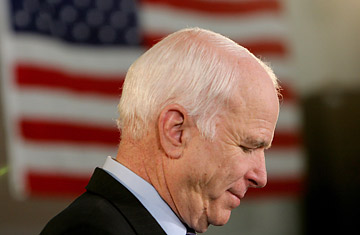

AS a candidate who relies on his carefully cultivated image as a straight-talking, maverick, John McCain has few issues as symbolically important as torture. No Republican has been as outspoken an opponent of prisoner mistreatment and abuse as McCain, and his own painful experience as a prisoner during the Vietnam War has granted him a unique moral authority on the issue.

So there is nothing the Democrats would like to do more than portray McCain as a rank hypocrite, someone who has sidled up to George W. Bush and flip-flopped on torture, all for political gain — which is exactly what Democratic National Committee chairman Howard Dean claimed in March. "It is shameful that George Bush and John McCain lack the courage to ban torture," Dean said in a statement. "And it is reprehensible that McCain changed his position on torture just to win an election."

Dean's statement, distributed in a press release, was a political attack meant to raise questions among independent voters. And as with most political attacks, it turned a grain of truth into a misleading landslide of overheated accusation. A review of the record shows that McCain has neither changed his position on torture nor taken sides with President Bush on the substance of the issue. But at a time when new details are emerging of the Administration's intimate involvement with formulating specific detainee interrogation practices, the Arizona Senator does now find himself in the uncomfortable position of agreeing with President Bush on a key election-year vote about those very same controversial policies.

At issue is a Democratic proposal to require the U.S. intelligence community to limit its interrogation techniques to those contained in a military training book called the Army Field Manual. Several Democrats who have received classified briefings on the current CIA interrogation program have said that the U.S. continues to approve of methods that they believe to be immoral and illegal. The CIA will not discuss the methods, except to say that waterboarding, a form of simulated drowning historically considered to be illegal, is no longer employed.

McCain has long argued that the Bush Administration overstepped its legal authority by approving techniques like waterboarding, and has successfully championed two efforts to try to limit the White House to the plain language of international treaties, which ban cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. McCain has also spoken in opposition to other techniques in the CIA arsenal like sleep deprivation and the use of stress positions, both of which were employed by the North Vietnamese during McCain's captivity as a prisoner of war and may still be employed by the CIA.

But on this latest piece of legislation, which arose during the heat of the primary campaign and may surface again later this month, McCain sided with Bush in opposing a further restriction of CIA techniques. Despite the claims of some partisans, McCain's decision was not a flip-flop, but rather the continuation of a position he took in 2005 when he first championed a bill to restrict the Bush Administration's ability to mistreat detainees.

"The field manual, a public document written for military use, is not always directly translatable to use by intelligence officers," McCain explained in February, reiterating his position from 2005. He added that the CIA should be allowed to use "alternative interrogation techniques," that are not otherwise outlawed as unduly coercive, cruel, inhumane or degrading. McCain has not publicly described the techniques that he believes fall into that category.

Some human rights observers say McCain's latest position is best explained as a symptom of exhaustion at fighting an Administration that has continuously resisted efforts to clearly outlaw practices like waterboarding. "I don't believe John McCain is comfortable with the current CIA program," said Tom Malinowski, the advocacy director for Human Rights Watch, who has worked closely with McCain and his staff on these issues. "I think McCain just reached a point where he didn't want any more confrontations with the White House. He wanted to win the White House."

McCain senior adviser Mark Salter said the candidate continues to monitor whether the techniques employed by the CIA officials pass legal muster. "If McCain has reason to believe that they have crossed the line, he will litigate that," Salter said, explaining that the Senator might discuss these concerns publicly or privately. "McCain communicates his view directly to the people doing it," Salter added, in reference to interrogation procedures.

To understand the complexities of McCain's position, it is first important to understand the legal game of hide and seek that the torture debate has become. Long before Bush Administration legal memoranda made techniques like waterboarding permissible for CIA detainees, many in Congress and the legal community assumed such methods were illegal under international agreements and U.S. criminal law. "There really wasn't any ambiguity in terms of waterboarding," explains Jonathan Turley, a professor at George Washington University Law School.

But since September 11, 2001, the legal waters have been muddied by repeated attempts by the Bush Administration to further define the meaning of the law. According to statements by CIA director Michael Hayden, three detainees in U.S. custody have been waterboarded. To permit these and other techniques, the White House and the Justice Department developed new definitions for terms like "torture" and "detainee" and expanded theories about the power of the President to override congressional oversight in time of war. A 2003 memo by John Yoo, a former Justice Department official, which was declassified last week, went so far as to discuss the potential of the President to approve the maiming, drugging or applying "scalding water, corrosive acid or caustic substance" on detainees.

In the spring of 2005, McCain began the process of formulating legislation to prevent a use of such extreme techniques and some of the sanctioned abuses at Abu Ghraib. Initially, McCain's staff proposed and circulated a bill remarkably similar to the Democratic language McCain now opposes. In a draft proposal, dated May 17, 2005, and obtained by TIME, McCain's staff specifically outlined a plan to make the Army Field Manual "the basis for a uniform standard adhered to by all elements of the United States Government." Another section said that no person under U.S. control could be treated or interrogated with techniques "not authorized by or listed in" the manual. But in the end, after consultation with fellow Senators and others, McCain and his staff did not adopt this draft language.

"It is standard operating procedure to go through numerous drafts before a bill is actually ready for introduction," said Brian Rogers, a McCain campaign spokesman, who added that he had no knowledge of the draft version of the bill.

When McCain publicly introduced his bill, which was later called the Detainee Treatment Act, he had narrowed the scope to require the field manual's use only for the military interrogations or interrogations on military property. But the McCain proposal did also make clear all U.S. Government agencies were banned from employing "cruel, inhuman or degrading" treatment of prisoners, as described by the U.S. Constitution and an international convention against torture, for which the United States is a signatory. A year later, McCain supported another bill, called the Military Commissions Act, which again made it a clear criminal act to employ "cruel or inhuman" treatment, as described by the Geneva Conventions.

"Cruel and inhuman treatment is defined as an act intended to inflict severe or serious physical pain or suffering," McCain explained on the Senate floor, during this second effort. "Such mental suffering need not be prolonged to be prohibited. The mental suffering need only be more than transitory." McCain has said he was assured by government officials that one of the most extreme techniques, waterboarding, was illegal under these laws.

The problem with all of these measures was that they continued to depend on interpretation by Bush Administration lawyers, who continue to be both secretive and evasive of congressional intent. As recently as February 6, the day after the Super Tuesday primary, a White House spokesman refused to rule out the future use of waterboarding as a technique for high-value detainees. The Attorney General has also declined to say that the technique, or other extreme techniques, are outlawed. On March 8, Bush vetoed the latest congressional attempt to force the CIA to adhere to the Army Field Manual, a rule book that prescribes mostly psychological methods of interrogation, and clearly prohibits the use of forced nudity, waterboarding, hooding and the use of military dogs. Congressional Democratic leaders have not yet announced if they plan to bring up the issue again, but they are unlikely to muster enough votes to override the veto.

Though McCain supports the President's position on the veto, he has spent the better part of a year on the campaign trail speaking out against waterboarding and other extreme interrogation methods as forms of illegal torture. In recent weeks, as it became clear that he would win the Republican nomination, his direct criticism of the Bush Administration has softened. "It is unfortunate," he said on the Senate floor on February 13, of the Bush Administration's refusal to call waterboarding illegal. "It would be far better, I believe, for the Administration to state forthrightly what is clear in current law."

His words, however, have had no effect. To this day, the Bush Administration continues to ignore McCain's advice.