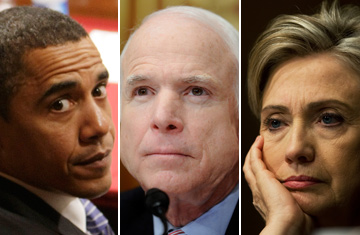

Hillary Clinton rested her chin on her right hand, and wore her glasses to read the poster board graphs. Barack Obama reclined in his chair with a studied look. John McCain exuded optimism.

At some point during Tuesday's roughly seven hours of grueling Senate hearings, each of the three remaining candidates for President got their chance to question the Bush Administration's top Iraq diplomat and commanding general about the uncertain progress of the war effort one of them will soon be responsible for. And as much as each used the proceedings to state their already widely known views of the conflict, they also helped begin to turn a public debate that had been mired in campaign-trail name-calling and misinformation into a more specific exchange about the difficult choices ahead. A discussion about benchmarks and troop levels turned into a conversation about the compromises the American people would be willing to accept to wrap up the conflict and redistribute the nation’s military might. "I'm trying to get to an endpoint," said Obama at one point. "That's what all of us have been trying to get to."

The day began as expected. The Republican Party's nominee for the White House, McCain, started the Senate Armed Services Committee hearing just after 9:30 a.m. by framing the debate in Iraq in the same stark terms as he does on the stump—a clear choice between victory and defeat, continued commitment and hasty retreat. "We are no longer staring into the abyss," McCain said, citing the recent trends of reduced violence. "And we can now look ahead to the genuine prospect of success."

As he has often done before, McCain then defined his vision of success: "A peaceful, stable, prosperous, democratic state that poses no threat to its neighbors and contributes to the defeat of terrorists." Shortly after finishing his questioning, McCain left the hearing room.

Hours later, the Democratic candidates for president offered their expected rebuttals. Both Clinton, at the Armed Services gathering, and Obama, at the Foreign Relations Committee hearing, spoke out in favor of a very different strategy for Iraq, describing the current commitment as unsustainable and unsatisfactory. But they also tried to probe the two witnesses, Gen. David Petraeus and Ambassador Ryan Crocker, for some acknowledgment that failure to meet McCain's goals was possible, and worth discussion.

"What conditions would have to exist for you to recommend to the President that the current strategy is not working?" Clinton asked of Petraeus.

"If we were able to have the status quo in Iraq right now without U.S. troops, would that be a sufficient definition of success?" Obama asked of Crocker.

The leaders of the war effort failed to answer the questions directly. Petraeus responded with vague declarations. "It's not a mathematical exercise," he said, in response to Clinton. "War is not a linear phenomenon," he said at another point, twisting his own metaphor. "It's a calculus, not arithmetic." He offered other bureaucratic koans, saying more than once, "It's a process rather than a light switch," to describe the process of building up Iraqi capabilities.

For his part, Crocker declined to speculate on the specific compromises short of a total victory that could be acceptable. "I don't like to sound like a broken record, but this is hard and this is complicated," he said when confronted by Obama about conditions that would allow a withdrawal.

But despite the lack of answers, the discussion about the acceptable compromises had the effect of elucidating the complex realities of the Iraq situation. It also gets at the heart of the choice that will be facing voters come November.

McCain has promised to campaign in favor of an open-ended commitment with the clear goal of achieving a broad victory of a stable, functioning nation. The Democratic candidates will campaign on the promise of a limited commitment that would willingly leave behind a less stable nation to reduce the U.S. cost of blood and treasure, while allowing for an increased military commitment in Afghanistan to fight al-Qaeda and the Taliban. McCain has not yet defined any limits on his commitment, if the U.S. effort began to fail, and the Democrats have yet to clearly define the extent of instability in Iraq that would be acceptable to leave behind.

As it stands, the tenuous facts of the Iraq situation are widely held. In recent months, the level of violence in Iraq has decreased in response to an increase in U.S. troops. But both Crocker and Petraeus testified that the gains were "reversible," and largely dependent on a continuation of political reconciliation in the country, which they both described as being frustratingly slow. The strain on the military remains severe, and the costs remain steep. As Sen. Joe Biden put it, "We have to spend $12 billion a month, we're going to probably sustain 30 to 40 deaths a month and we're going to have somewhere around 225 wounded a month."

Both Bush Administration witnesses declined to identify any clear benchmark by which the effort could be judged a success or failure. Petraeus said he expected to soon halt the planned drawdown of troops in Iraq for a "45-day period for consolidation and evaluation as to examine the situation on the ground" which would be followed by an indeterminate period of "assessments." "I'm not sure what the difference between evaluation and assessment is," quipped Michigan Sen. Carl Levin, the Democratic chairman of the Armed Services committee at one point.

Notably, the skepticism of Obama, Clinton and other Dems was joined by a number of Republican Senators who have long soured on the current war effort. The group includes Susan Collins of Maine, George Voinovich of Ohio, Chuck Hagel of Nebraska, and Richard Lugar of Indiana. Independent Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut, who caucuses with the Democrats, joined McCain in speaking out forcefully in favor of the current strategy.

The day ended with no clear resolution, but of course, none was expected. The Democratic leadership in Congress has been largely frustrated in its efforts to shift the Bush Administration's war policy. That issue will now be placed before voters, and decided in the presidential election. More than anything, Tuesday’s marathon session was an opening glimpse of the debate that is sure to dominate the campaign this fall.