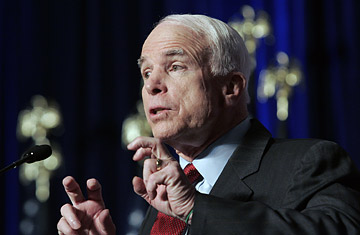

John McCain gestures during a speech before the Conservative Political Action Conference in Washington, Thursday, February 7, 2008.

For an old battle-scarred warrior, John McCain has the smile of a peacemaker. So he knew what do to when the boos and jeers finally came Thursday at the Conservative Political Action Conference. He flashed his teeth and held up his palms, as if he was basking in the glow of a wood fire. Okay, he was saying to the suddenly hostile crowd, let me have it. Tell me how you really feel.

After about five seconds, his charm won out. The boos were overwhelmed by cheers, and McCain was able to finish a sentence about his unpopular plans to deal with illegal immigration. "I respect your opposition," he told the thousands who had gathered — which was the point of his appearance at the conference on the very day that he effectively sewed up the Republican nomination.

To win the presidency, McCain knows he must prevent an all-out civil war within the Republican Party, a battle that has been brewing in recent days as talk radio giants like Rush Limbaugh lambaste him as a false conservative who supports campaign finance reform, global warming regulations and other right-wing heresies. This means that unlike other presumptive nominees in his situation, McCain must tack to the right before he moves to the center for the general election. That fact came into stark relief Thursday night when word leaked that James Dobson, the evangelical leader, had endorsed Mike Huckabee, who dramatically trails McCain in the delegate race but has proven to have a strong conservative following, especially in the South.

The address to the conservative conference was key to McCain's effort, especially since he shunned the gathering a year ago, apparently fearful of receiving a less welcoming reception than his arch-rival Mitt Romney. But on Thursday, two days after his disappointing showing on Super Tuesday, Romney returned to CPAC to bow out of the presidential race, clearing the way for McCain to begin a sort of dating ritual with the movement he has never followed step for step. He faces an uphill battle, but it is one he can overcome.

"I am mortified by what is happening right now," muttered Daniel Lipian, 24, the chairman of the Ohio College Republicans, and one of the dozens of young people who had booed throughout McCain's speech. "I respectfully disagree with jumping on the bandwagon of someone who has a consistent record of going against the grain of our party." But Lipian also knew that his boos were no match for a Republican Party that has been trained for decades to hate Democrats, not their own, and put aside their differences to come together for the good of the party. In the conference's exhibit hall, one could find "Don't Tax Me Bro" wristbands, an unending array of unflattering Hillary Clinton pictures, and "Chappaquidick Swim Club" t-shirts, but no garb that targeted a fellow Republican.

By the end of the day, even the Club For Growth, a conservative group that was essentially founded to destroy insufficiently orthodox Republicans, had released a statement announcing it could work with McCain. "Senator McCain deserves some credit for making a conscious effort to reach out to conservatives at CPAC today," wrote Pat Toomey, the group's president.

Elsewhere in Washington, other conservatives were sounding similar friendly themes about an imperfect conservative overseeing the party of Ronald Reagan. Anti-tax activist Grover Norquist, a longtime foe of McCain, predicted that the current nervousness about McCain would dissipate over the coming months, assuming that the candidate continued to sound solidly conservative themes on the trail. "There will be a low-boil, low-level rumbling that will diminish," Norquist said. "McCain didn't have a voice in this campaign until after New Hampshire. So he is new to a lot of people."

As part of this courtship, McCain has been surrounding himself with loyal members of the movement. Before addressing CPAC, he was introduced first by former Virginia Sen. George Allen, a darling of many conservatives, and Oklahoma Sen. Tom Coburn, who is known as an ideological purist on Capitol Hill. "He doesn't have a secret plan to enact blanket amnesty as President," Coburn told the crowd, about McCain's plans on immigration. "And if he did he knows I'd kill it."

For his own part, McCain did his best to offer the crowd the red meat it craves. He vowed to lower taxes, appoint judges "of the character and quality of Justices Roberts and Alito," and reject "big government" solutions to health care, like the ones being offered by the Democratic candidates. He also hammered away on his own support for the current military effort in Iraq, declaring, "I intend to win the war." As for his differences with movement conservatives, he promised mainly to listen respectfully to those the ideologues represented in the room.

"We have had a few disagreements," McCain said. "And none of us will pretend that we won't continue to have a few. But even in disagreement, especially in disagreement, I will seek the counsel of my fellow conservatives. If I am convinced my judgment is in error, I will correct it. And if I stand by my position, even after benefit of your counsel, I hope you will not lose sight of the far more numerous occasions when we are in accord."

None of this was good enough for Lipian, a student at Bowling Green State University, who was about four years old when Reagan left office. "I will not vote for anybody," he vowed of the general election in November. "A vote for John McCain is like a vote for a Democrat. I'm sorry." But even in the hotel ballroom, in the belly of the conservative beast, Lipian's views represented little more than a small, albeit vocal, fringe.