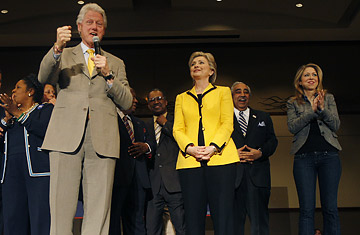

Former US president Bill Clinton introduces his wife, Hillary Clinton during a campaign rally in Charleston, South Carolina, on January 25, 2008.

"There may be a better salesman than I am," Bill Clinton said, smiled, then paused as chuckles rippled through the audience. A better salesman? On what planet? This was classic, postpresidential Clinton, able to riff on his well-earned reputation as a mythic slinger of bullpucky. I should add that the topic in question was nuclear nonproliferation. He had the audience hanging on his every word about ... nuclear nonproliferation. The Bush Administration wanted to develop two new nuclear weapons, he said, while it was trying to persuade the Iranians to stop enriching uranium. "There may be a better salesman than I am," he said, "but that's a tough sale. We're telling the Iranians, You can't have any of something we want two more of.'"

His voice was hoarse. His cheeks were splotched with wine-red daubs of what looked like clown rouge. He seemed a bit disheveled, wearing a light gray-green suit and a garish yellow tie, a costume more fitting for a used-car salesman than a former President. An aide told me that Clinton had pulled a Clinton the night before. Unwilling to stop campaigning after his last event, he had gone to the cafeteria at the University of South Carolina. About 15 kids were there, and they started texting their friends. Pretty soon several hundred kids had gathered, and Clinton held forth for two hours, answering their questions.

There are no 12-step programs for political junkies. And for Bill Clinton, there is no more powerful jones than grabbing an audience, explaining something really complicated and worthy — nuclear nonproliferation — in a way that keeps the crowd completely enthralled. For a man known for his cornucopia of appetites, this is the greatest hunger. There is no controlling it, especially when he is in a defiant mood, under attack for his latest eruption of narcissism. It's his way of saying "No! Look! I'm not overwhelmingly selfish — just extremely, passionately interested in making the world better for you!"

I should add a bit more context here. The speech was given the night before the South Carolina primary. The setting was a historic spot, Penn Center on St. Helena Island, a complex of rude buildings that had served as a center for the civil rights movement, dating back to the Civil War. The crowd, however, was overwhelmingly white — a silent reproach to Clinton by his best-loved constituency, those unutterably decent, hardworking, middle-class, churchified African Americans. They had been shocked and hurt, and then enraged, by his foolish, two-week effort to diss Barack Obama. The next crowd, at Hillary Clinton's closing rally in Columbia, was equally pale and must have been deeply depressing to the ex-President. I remembered a huge interracial crowd in the Mississippi Delta, late in Clinton's presidency. I was standing next to Jesse Jackson, who was quite moved by the "glorious" sight of whites and blacks salt-and-peppered through the audience. I asked Jackson why he found it so moving; he had seen crowds like that before in the South. "But look," he said. "They're talking to each other!"

That was one of the great unquantifiable achievements of Clinton's presidency: he brought whites and blacks together, after years of racial tension, even within the Democratic Party. He was the first President to talk easily with blacks, as equals, without condescension. He was the best white politician I have ever seen in a black church. The bond he built with that community seemed unbreakable. And so it was shocking — heartbreaking — to see it shattered in South Carolina, shattered by a thoughtless, solipsistic need for victory at any cost.

I was told by someone close to the President that he thinks he won New Hampshire for Hillary Clinton. If so, he is wrong. Senator Clinton won New Hampshire on the strength of her bond with working women. Indeed, I would guess that she was well on her way to winning the Democratic nomination on the strength of her performance in debates — in which she routinely left Obama seeming green and tongue-tied — and the strength of the smart, nuanced positions she took on issues like health care and energy independence. But most of all, Clinton conveyed the impression that she was a rock, an unflappable presence in a stormy time for our country. You might disagree with her, but she had positioned herself as the ultimate, reasonable alternative to the dim-witted machismo of the Bush presidency.

In the past two weeks, though, Bill Clinton has redefined his wife's campaign. He has made it a co-candidacy. He has cheapened it by using cheesy, misleading tactics against Obama. He began this the night before the New Hampshire primary, when he called Obama's antiwar opposition "a fairy tale," which was, well, bullpucky. Obama spoke out against the war before it began. When he reached the Senate, Obama had to deal with the awful reality on the ground: we had troops there; there was chaos. He proceeded to vote exactly like other Senators who had opposed the war — in favor of funding the troops, hoping for progress. As Iraq metastasized into a civil war, he began to vote for a responsible withdrawal. That Bill Clinton would turn this into an attack against Obama was almost as absurd as Clinton's turning Obama's statement that Ronald Reagan had changed the trajectory of the nation — and that, for a time, the Republicans had been the party of ideas — into a claim that Obama thought G.O.P. ideas were better. Clinton, after all, had said the same sort of things about Republicans in 1992. And he had been tougher on Democrats, decrying "the brain-dead politics of both parties in Washington." Indeed, almost everything Clinton said about Obama smacked of cheap political trickery (which is not to absolve the Obama campaign of some low moments of its own, but these were far outnumbered by the lame Clinton efforts to do a paint job on Obama).

It is difficult for people like me to gauge accurately the public impact of discrete campaign events; we are just too close to the heat of the process. I would guess that most voters aren't even aware that Clinton attempted some half-assed mudslinging in the past two weeks. But even the most casual observer is aware of this: at a moment of crisis in Hillary Clinton's campaign, Bill Clinton was suddenly back and all over the news. His reappearance made her seem weak, unable to defend herself. It raised the most fundamental question about her candidacy: If she is elected, who exactly will be President? What happens when there is a real crisis? My guess is, she'd be able to handle almost anything ... except him. I could easily see him jumping the shark, sending mixed messages when a single voice of authority is crucial — especially if the crisis involves one of his specialties, like the Middle East.

It is entirely possible that Hillary Clinton will win this nomination. One on one, she simply seems stronger than Obama. But two on one, she seems weaker. And if she wins the nomination, you can bet the co-presidency question will be front and center in the general election. It is, therefore, vital that she address it now. She's got to say something like, "Bill's a fighter, and he got a little too feisty these past few weeks. He knows that, and he's decided to return to his charitable work for the duration of the campaign. I will continue to run as I will govern — on my own."